World

China: A not so Happy 50th Birthday for the Cultural Revolution

The enormously important Cultural Revolution in China has just had its 50th birthday, although the parents are no longer around to celebrate. The heirs to China’s government are trying hard to avoid even noticing it happened. But J. BROOKS SPECTOR is not shy to take a look.

Back in the 1970s, this writer worked with a scholar of Chinese literature and language who was also a US diplomat. This individual had been an American diplomatic visitor to China as part of his work, shortly after the bilateral relationship opened. His trips to China had come along just after the beginning of the US-Chinese diplomatic dance that came from Henry Kissinger’s secret visits, Richard Nixon’s ceremonial trip, and the ping pong diplomacy that helped nudge it all along.

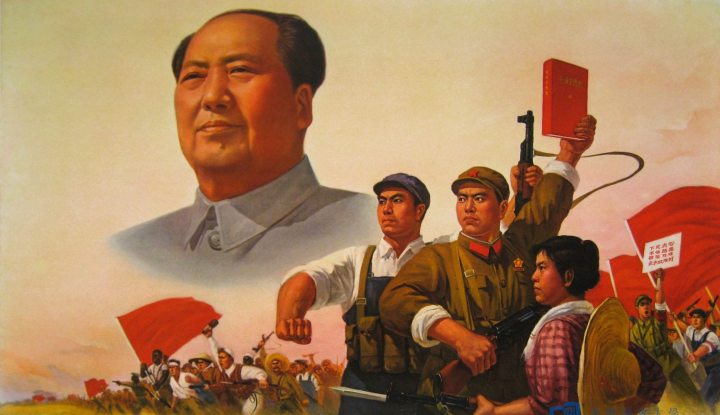

After one early trip there, he returned to his office and hung a picture he had obtained in China on the wall of his office (see below).

Captioned, “With You in Charge, I Am at Ease”, this poster depicted Mao Zedong in a meeting with the rising new Chinese Communist Party leader, Hua Guofeng. Hua was the man who had come to power amid the nationwide, roiling chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Hua’s mandate had been to bring to an end the turmoil of a movement that had been taking place in Mao’s name. (That vast uncontrolled, destructive movement actually began this week, on the 16th of May, 50 years ago. ) As he gained control over the country, Hua eventually was able to bring to an end a full decade of that chaos. In the process, Hua ousted the Gang of Four (the tight ring of radical leaders of the movement that included Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife) from their positions of authority – and eventually having them arrested as well.

.jpg)

Photo: “With You in Charge, I Am at Ease”, a poster depicting Mao Zedong in a meeting with his immediate successor, Hua Guofeng.

Despite the vast continental upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, the social-political movement that nearly flat-lined the country’s economy, that sent many of the nation’s brightest thinkers into difficult forced internal exiles and which – according to the best estimates – probably caused the deaths of a million-and-a-half people by the time it all came to an end, this anniversary has largely been ignored inside China, even as international news outlets have featured it prominently.

Then, on Tuesday, 17 May, the People’s Daily, the party’s official newspaper, ran a commentary that praised in no uncertain terms the 1981 Communist Party resolution that had thoroughly condemned that Cultural Revolution. That movement had been launched by Mao Zedong to institute, and then enforce, a radical egalitarian movement that quickly exploded across the nation. Historically, the Cultural Revolution had come about around a decade after the hugely unsuccessful economic project, the Great Leap Forward, and like the activism of the student and young adult movements in Western Europe, Japan and the US, the Cultural Revolution drew upon the vast size and energies of a postwar baby boom generation’s demographic cohort.

In that People’s Daily article, the paper insisted, “Our party has long taken a solemn attitude toward bravely admitting, correctly analysing and firmly correcting the mistakes of our leadership figures.”

This can be read as a somewhat oblique reference to the fact that for years, the ruling party has suppressed any open discussion of that tumultuous decade, worrying such discussions would inevitably lead to questions about the party’s own legitimacy and monopoly as the nation’s unchallenged leadership. In the end, such reconsiderations and re-evaluations of the Cultural Revolution would end up evolving into direct criticism of the still-revered figure of Mao Zedong.

As Frank Dikotter, author of The Cultural Revolution: a People’s History, told CNN on the anniversary of the movement’s beginning, “The entire history of the Chinese Communist Party revolves around the personality of Mao, which is why the Party will never, ever promote a critical examination of its own of its own history.”

As a result of just such concerns, close observers of China believe this is the reason no official commemorations of this enormous upheaval have been scheduled by the government.

In fact, drawing upon that legacy, ever since he became the country’s supreme political authority back in 2013, China’s current President, Xi Jinping, has continued to make frequent references to Mao’s leadership and has deployed the kind of political stagecraft that offers clear echoes of the Great Helmsman’s own autocratic rule.

Speaking to foreign media about this comparison, Yu Xiangzhen, a former Red Guard, had said, “Fifty years on, however, I am worried by the increasing leader-worship we see in state media, similar to the ideological fervour that surrounded Mao. We must stay vigilant. We can’t have the gruesome brutality of the Cultural Revolution start again.”

The Red Guards, of course, were the mass formations of youthful shock troops that actually demanded and then carried out most of the harsher efforts to punish an older Chinese economic, bureaucratic and cultural leadership.

As the party’s public voice, the People’s Daily voiced its agreement with that judgment of the party over three decades ago, it wrote, “The Cultural Revolution (as a catastrophe) has withstood the test of time and it remains unshakably scientific and authoritative. We summarise and absorb history’s lessons with the goal of using history as a mirror to better move forward.”

Their commentary added that the Cultural Revolution had been “mistakenly launched” and had caused “comprehensive and serious” damage to the country.

It went on to say, “History has fully proved that the Cultural Revolution was completely wrong in theory and in practice. It was not and will not be any revolution or social progress in any sense.” No wiggle room there about a trial run of creative destruction that went seriously awry. And it thus sounded pretty definite about its trashing of a full decade’s worth of a national experiment with mob rule.

Then, in a separate (but related) piece in the Global Times, a sister paper also published by the People’s Daily, that article explained that the events of a half-century ago had subsequently inculcated an abhorrence of disorder and craving for stability among the Chinese public as a result.

“Completely denying the values of the Cultural Revolution is not only an understanding throughout the party, but also a stable consensus of the whole of Chinese society”, it wrote. It then went on to say, “We have said ‘bye-bye’ to the Cultural Revolution. And we can say it again today that [the] Cultural Revolution cannot and will not start all over again. The Cultural Revolution doesn’t have its place in today’s China.”

Andrew Walder, author of China Under Mao: A Revolution Derailed, explained to international news channels that this period remains an awkward topic in China. “The government today is nowhere near as open as discussing this period as they were in late 1970s and 1980s when they widely described what happened in great detail to turn the country in a new direction.”

That new direction, of course, would have been the reorientation towards capitalist economic openness as exemplified by Deng Xiaoping’s famous phrase, “To be rich is wonderful”, that helped open the floodgates to turning China into the world’s factory – the phenomenon that affects the entire globe now.

The paradox of contemporary China, of course, is that the country seems to be hurtling headlong, full steam ahead, down the capitalist highway, even as Mao’s political legacy remains the nation’s official orthodoxy. Eerily, it is embalmed in a way that mimics his preserved corporeal remains that are on public display.

Photo: A picture made available 12 May 2016 shows a vendor sitting beside a stall that displays various items depicting the late Chinese leader Mao Zedong at the Panjiayuan flea market in Beijing, China, 8 May 2016. Memorabilia depicting Mao Zedong and items carrying themes reminiscent of China’s Cultural Revolution are still sold at Panjiayuan market, a compound of various stalls selling antiques on the southeast side of Beijing. The 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution falls on 16 May. EPA/ROLEX DELA PENA.

In discussing this apparent paradox, the Financial Times, in looking at the official Cultural Revolution anniversary that wasn’t, wrote, “During Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution, which he saw as a path towards absolute power, as many as 36-million people were persecuted and up to 1.5-million were killed. At its vanguard were millions of young ‘red guards’ who attacked the country’s institutions, including the party, and worshipped Mao as his personality cult took root. Mao, who died in 1976, has since been judged ‘70% correct and 30% wrong’.”

Nevertheless, the ruling party was reported to be bracing itself for a plethora of harsh, stinging recollections from some of the many millions who were persecuted during that period. And it was also caught off guard by a celebration of that difficult period that took place in the capital earlier in the month. As the Financial Times reported on that incident, “A gala held at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing earlier this month celebrated that version of history with cultural revolution-themed singing and slogans, including ‘people of the world unite to destroy American imperialism!’”. That was obviously not quite the message China wanted to send these days.

The Financial Times went on to add, “After word leaked out on social media, the sponsors quickly claimed they had been duped by an ‘unauthorised’ event organiser while censors raced to delete all pertinent posts.”

As if in reply, the People’s Daily’s view of things then concluded, “We must firmly keep in mind the historic lessons we learnt from ‘cultural revolution’, firmly adhere to the party’s political conclusions on the cultural revolution, and resolutely prevent and combat the interference from the ‘left’ and the right concerning cultural revolution issues.”

Back at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution itself, Chairman Mao had challenged the nation’s young people to purge all those “impure” elements of Chinese society and then revive the revolutionary spirit that had led to victory in the civil war nearly two decades earlier – and then on to the victorious formation of the People’s Republic of China. Thereafter, for a full decade, the Cultural Revolution rolled onward until until Mao’s death in 1976. Its legacy has roiled Chinese politics and society for years – and its ultimate impact remains an unresolved question for China, regardless of what the People’s Daily may have pronounced on the matter.

Beyond contemplating China’s current conundrum about how to respond to the Cultural Revolution, it is important to look back at what the Cultural Revolution was, given all its effects. By the mid 1960s, Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong had come to feel that the current party leadership in China, as in the Soviet Union, was moving too far in a “revisionist” direction, with their growing focus on technological and managerial expertise, rather acting with a firm grip on ideological purity. In fact, Mao’s own position had already been weakened by the failure of the “Great Leap Forward” and the severe economic crisis that had come out of it afterwards.

As a result, in order to reinvigorate the party’s revolutionary ardour, Mao had brought together a close-knit group of radicals, including his wife Jiang Qing and defence minister Lin Biao, to help him attack the larger circle of the party’s current leadership and thus reassert his revolutionary style authority. To help nurture the growing personality cult around Mao Zedong as part of the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, Defence Minister Lin Biao ensured that the “Little Red Book” of Mao’s quotations – the diminutive bestseller everyone in China had to read, carry and wave about – was printed in the hundreds of millions of copies and then distributed throughout the country.

Officially, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution – its formal name: the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution – in August 1966, at a Plenum meeting of the Communist Party Central Committee. Then, shutting down the nation’s schools, he called for a national mobilisation of the country’s young people to bring all those current party leaders to book for their backsliding embrace of bourgeois values and their visible lack of revolutionary spirit. This movement escalated quickly when students began forming ad hoc paramilitary groups, the Red Guards, which then began to physically attack and stridently harass members of China’s technocratic leadership and the nation’s intellectuals – rather broadly defined. All of this growing fervour fed a personality cult around Mao.

In the first two years of the Cultural Revolution, President Liu Shaoqi and other Communist leaders were removed from power. Liu was beaten and then imprisoned, and died in prison in 1969. Inevitably, different factions of the Red Guards started fighting for control of this loose movement and numerous Chinese cities reached near-anarchy by September 1967 as Lin Piao was ultimately forced to dispatch army units to restore order. Red Guard leaders in numerous cities were rusticated to bring back some order. During all the chaos, the Chinese economy dropped by 12% between 1966 and ‘68.

In 1969, Lin officially became Mao’s successor. He soon used the excuse of border clashes with Soviet troops to institute martial law. Disturbed by Lin’s premature power grab, Mao began moving against him with the help of Zhou Enlai, still China’s premier, splitting the ranks of power atop the Chinese government. In the midst of all of this, in September 1971, Lin died in a mysterious plane crash in Mongolia, apparently while he was attempting to flee to the Soviet Union, and members of his high military command were subsequently purged as Zhou took over increased control of the government. Lin’s brutal end seems to have generated feelings of many Chinese citizens to become disillusioned over the ongoing course of Mao’s “revolution”, which seemed to have devolved instead into more garden variety power struggles.

Zhou moved to restabilise China by reviving the educational system and bringing back many former officials to power. In 1972, however, Mao suffered a stroke even as Zhou learnt he had cancer. The two leaders swung their support to Deng Xiaoping (one of those who had been purged back at the onset of the Cultural Revolution). This move was, however, strongly opposed by Jiang and the rest of the Gang of Four. Over the next several years, the Chinese political world teetered between the two sides. The radicals finally convinced Mao to purge Deng in April 1976, after Zhou’s death, but after Mao died in September of the same year, a coalition of civil, police and military leaders finally pushed the Gang of Four out of power and into the docket. Deng regained power in 1977, and would substantially exercise control over Chinese government for the next 20 years.

Looking back at the revolution’s legacy, approximately 1.5-million people were killed during the Cultural Revolution, and many millions more suffered imprisonment, seizure of their property, torture or general public humiliation. While the Cultural Revolution’s short-term impact may have been largely in China’s cities, its longer-term effects have worked their way through the entire country for decades to come. Mao’s large-scale attack on the party and system he had effectively created eventually produced a result opposite to what he presumably intended, leading many Chinese to lose faith in their government altogether. But the most important, ironic, effect was to ready the Chinese people for the startlingly new economic system. The upheavals of the Cultural Revolution had prepared the ground for its birth. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider