Africa

How to organise an opposition: Lessons from Nigeria

Zille, Ramphele, take note: it’s not impossible to form a viable opposition coalition. Even Nigeria has pulled it off. Anyone dreaming of evicting the ANC from the Union Buildings should be paying very close attention. By SIMON ALLISON.

Nigeria and South Africa have a lot in common. They’re both continental superpowers. Both are fledgling democracies, dominated by a single party. Both suffer from weak, compromised presidents and high-level corruption. But there is one thing Nigeria has going for it that South Africa currently lacks: a viable opposition.

This is a very new development for Africa’s most populous country. Since 1999, when the current era of multiparty democracy began (there have been a few other attempts in Nigeria’s post-colonial history), the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) has won every single general election: first under Olusegun Obasanjo, who continues to meddle behind the scenes; then the late Umaru Musa Yar’Adua; and finally Goodluck Jonathan, the sitting president, who wrapped up the 2011 poll with a hefty 58.89% majority.

In that time, there have been challengers to the PDP’s de facto one party rule, most notably the various political groupings organised by northern politician Muhammadu Buhari (he’s come second in the last three elections). But none have stuck. With a carefully cultivated constituency that crosses ethnic, religious and geographical divides, the PDP has been the only party able to generate national appeal. Buhari, for instance, while enormously popular in the Muslim north, doesn’t get much support elsewhere.

All this might be about to change. In the wake of the 2011 elections, Nigeria’s various opposition parties realised that none of them could challenge the PDP juggernaut by themselves. And so the All Progressives Congress (APC) was born, a coalition of four major opposition parties including Buhari’s and that of Nuhu Ribadu, a widely-respected corruption buster (think of him as Nigeria’s Thuli Madonsela).

But given the PDP’s large majority, even a united opposition is not enough to unseat it. A genuine electoral challenge requires a huge shift in support away from the PDP itself.

This is where it gets really interesting. The PDP has always been a big, messy tent of different belief systems and raging ambition. The squabbles and power-plays within the party itself can be epic. At the end of the day, however, conventional wisdom amongst most Nigerian politicians holds that prospects for political power are better inside the PDP tent than out.

That wisdom is not so conventional any more. The prospect of a viable, united opposition has proved tempting, and the PDP has been weakened by a series of high-profile defections (it is probably no coincidence that the defections are increasing in frequency as the next election, scheduled for 2015, gets closer).

In November 2013, five state governors formally switched allegiances. In December 2013, an astonishing 37 members of the House of Representatives crossed the floor, temporarily handing the APC a majority in the house. In January 2014, they were followed by 11 senators, who wrote an open letter to their former party explaining that they were tired of the “division and factionalism” of the PDP.

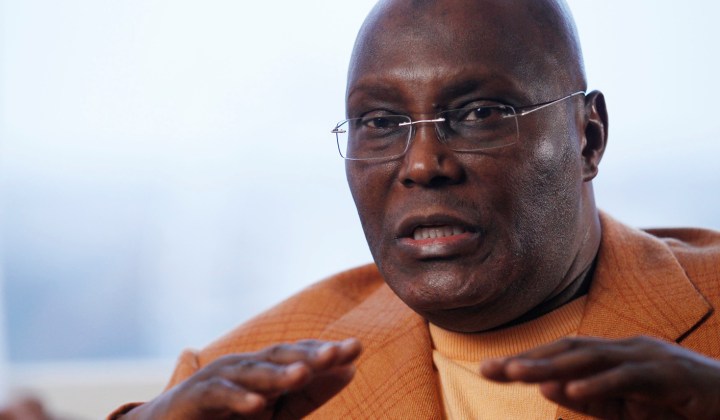

The highest-profile defection came this week, when former vice-president Atiku Abubakar formally made the move to the new opposition coalition. Although this news had had been expected for quite some time, it was no less momentous for it – political heavyweights don’t get much heavier than Abubakar. There is no doubt about it any more: the APC is a serious threat to Goodluck Jonathan and the PDP’s chances of re-election.

For this, Jonathan has only himself to blame. Taking over on Yar’Adua’s death, his leadership was divisive from the first. Many in the party saw Jonathan’s ascent to the top job, and consequent election campaign, as a violation of the unwritten PDP pact which promised that leadership would rotate between northerners and southerners. Jonathan is a Christian southerner. Yar’Adua was a Muslim northerner, and he was meant to have another six years in charge. Jonathan has also been accused of ruling the party (and the country) autocratically, freezing out potential challengers.

As president, Jonathan’s record is just as undistinguished. He’s been hopeless against the dangerous and ever-spreading Boko Haram insurgency, which has claimed thousands of lives on his watch. Levels of corruption remain as high as when he took office, and huge public protests forced him to scrap his one major policy initiative (the removal of the fuel subsidy).

Jonathan’s poor record offers an opening for the newly-strengthened opposition. But it’s Jonathan’s autocratic streak that is really working in the opposition’s favour, as sidelined, frustrated PDP leaders look for opportunities elsewhere. “The APC seems to be providing political shelter for PDP runaways and those whose political ambition could not be achieved within the PDP, and are therefore seeking another platform to obtain them,” explained Lagun Akinloye, Nigeria analyst for Think Africa Press, in comments to the Daily Maverick (Read his piece ‘Nigeria: Welcome to a two party state’ for more insight).

Akinloye warns, however, that this might eventually be the APC’s Achilles heel too – after all, the new party will not be able to accommodate all its new members in the lofty positions that they perhaps expect (who, for instance, will be the APC presidential candidate?). “Personally I do not see the glue of the APC sticking together,” he said. “The acceptance of Atiku Abubakar into their fold further calls into question their actual ideology or whether it is just an amalgamation of politicians on the outside joining together to force their way inside.”

But this welcome-all-comers approach could also be the APC’s ticket to victory. By refusing to get stuck up on the nitty gritty, the new party is able to offer something for everyone. A broad-based appeal has been the secret behind the PDP’s success for so long, and it might just work for the APC too.

Of course, if the APC actually does get elected, a near complete lack of policy means it is unlikely to govern particularly well (then again, it doesn’t have to do all that much to improve on the PDP’s record).

Either way, Nigerian politicians are showing the way for South Africa’s befuddled opposition, who struggle to organise a press conference let alone a coalition. The lesson is this: if you want your turn in power, you’re all going to have to try and get along first. DM

Photo: Nigeria’s former vice-president and presidential candidate in the upcoming elections Atiku Abu Bakar speaks during an interview at a hotel in London December 1, 2010. REUTERS/Andrew Winning

Become an Insider

Become an Insider