World

The Washington Post: The newspaper that once had it all

With The Washington Post now sold to Jeff Bezos as his personal possession after years of slow decline in influence and power, J. BROOKS SPECTOR reminisces about what that paper has meant to him over the years.

NB: The writer still reads The Post every morning, first thing, via Internet, and can still hum John Philip Sousa’s “Washington Post March”

Once upon a time there was no Internet, there were no cell phones, no SMSs, and nary a fax to be read. Back in those days, say the late 1970s, our family lived in the city of Surabaya, on the eastern side of the Indonesian island of Java. This was a big city, with several million inhabitants and a hinterland of many tens of millions more.

Back in Joseph Conrad’s day in the late 19th century, when he wrote books like Typhoon, Almayer’s Folly, Lord Jim and An Outcast of the Islands, Surabaya was the Big Apple of the East Indies. It had grown rich through near total control of international trade in tea, rubber, sugar, teak and other exotic woods, and copra shipped through its port.

In the 1970s and 1980s it was still a major port, even if it had become an increasingly hardscrabble, slightly down at the heels kind of place. Its polyglot population of Javanese, Madurese, Malays, Arabs and Chinese were sometimes pretty rough on each other (including the occasional ethnic riot), but everyone had immense pride in coming from the city where Indonesians carried out their first armed resistance against the return of Dutch colonial rule, following the Japanese surrender after World War II.

The city’s inhabitants were mostly Muslim, but there were significant numbers of Christians and even a small, remnant Jewish community. The leader of its small synagogue was the Muslim widow of a Baghdadi Jew who had headed the local chamber of commerce and who had held the Volkswagen franchise for East Java. In our time there the synagogue was finally deconsecrated after a century of service because the number of community members had finally fallen below the ritual threshold of 10 adult males, ending an era and inspiring a short story by novelist and travel writer Paul Theroux.

Assigned to this city, our tasks were to run the American cultural centre and library, its associated English language school and the US government’s international educational and cultural exchange programs. Around the corner from our downtown facility was our Soviet competition (we were still in the grips of the Cold War, of course), and down the road a bit were the American Consulate offices, and the French and German cultural institutes.

Every couple of months our library received a precious sea freight shipment of new books and magazines, with subscriptions ranging from Sports Illustrated, Art in America and Dance, to more politically oriented publications like The New Republic and Commentary magazines. Back before the Internet, these items were enormously valuable. Public libraries in that city were scarce and poorly stocked, and university libraries were usually years behind in importing expensive foreign-published academic publications for their study collections.

So that we could keep up to date on events beyond the meagre information gleaned from the local television station, the two locally printed broadsheets and the incessant rumour mill in the market, we scanned the airwaves with our shortwave radio for those fade in/fade out, crackling signals of news broadcasts from the BBC and VOA, or even Radio Moscow and Radio Beijing in English. As embassy employees we also received a daily transmission, The Wireless File (so named because from its inception in World War II onward it had been transmitted by radio waves and then converted into a long sheet of teletype-like print). It gave us the bare essentials of foreign policy related news from various newspapers, plus sports scores and lists of new diplomatic staff assignments around the world. But all of this barely helped keep us connected. After a few weeks we buckled and sent off a check to subscribe to an airmailed copy of The Washington Post Sunday edition, sent to us at outrageous cost.

The thick paper arrived tightly rolled up and wrapped in brown paper with a tiny sticker on it that indicated its date of publication. It became our habit to put each copy on a bookshelf as it arrived so that we always opened the oldest issue first each Sunday morning over breakfast, even if there was a month’s worth of newer editions already waiting in line. As we read the paper each Sunday, out there in our Joseph Conrad-like tropical garden, we’d slowly work our way through the entire paper.

First it was the “news and views style” Outlook section. Then it was the reviews and essays in Book World. The two magazines and the Style section, with the gossip columns, rumours and scandals of the high and mighty, came next. Then we read the sports section, the business reports, the local news portion of the paper, the comics (to check on Doonesbury), and then, finally, the front section with its news of the nation and the world. Reading it that way, in our garden, seated on our rattan chairs, we could easily pretend the paper had just been delivered on our doorstep that morning – even if it was actually at least three-week-old news. It didn’t matter. This indulgence helped us feel connected to the world, to Washington, and to the kind of American family tradition where the Sunday paper was an absolutely regular part of life.

Having grown up in the Washington area from middle school onward through my university years, reading The Post every day had become standard, just like most other people in the area. Yes, The Washington Star and the tabloid Washington Daily News were issued in the afternoon, but like most afternoon papers across America they were slowly fading away. With changes in reading habits, fewer and fewer people bothered to buy an afternoon paper for the day’s latest news, since the evening TV news broadcasts were inevitably more up to date than an evening paper.

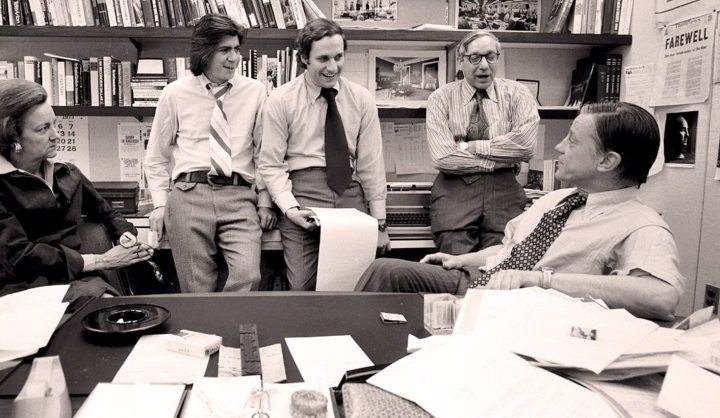

The Post finally seized media leadership in Washington in the early 1970s (perhaps even edging out the impact of The New York Times in the capital), partly through its publication of those secret Pentagon Papers (in association with The New York Times) and then from its dogged exposure of the scandals, and worse, associated with Watergate that finally drove Richard Nixon from the White House. Its reporters seemed to be everywhere in the world and across the country, and columnists Walter Lippmann, David Broder, George Will, Charles Krauthammer and Joseph Kraft, among so many others, were a babble of spirited argument across the political spectrum. Its prize-winning editorial cartoonist Herblock could, and often did, provoke American presidents to rage in impotent fury at their portrayal under the artist’s pen. Michael Dirda’s book reviews garnered one of many Pulitzer Prizes claimed by The Post writers over the years, and the acid-tipped pen of its high society maven, Sally Quinn, probably knew the secrets of every powerful person in the capital. And all this was under the lash of its chief editor, Ben Bradlee, a nobleman, a friend (and sometime enemy) of presidents and foreign potentates.

Back in the 1930s, Eugene Meyer, a young Federal Reserve Bank official brought to Washington by then president Franklin Roosevelt, had purchased the decidedly second-rate paper at a bankruptcy auction for much less than a million dollars. And as it passed on to his daughter, Katherine, and son-in-law, Philip Graham, the paper began its climb to respectability. When Philip Graham committed suicide, Katherine Graham hesitantly took charge, and then ultimately presided over its true glory days.

At its peak in 1993, the paper had nearly a million subscribers in the Washington area (out of a total population of around 3.5 million people). The parent company owned radio and television stations, held a series of smaller regional papers and bought a major educational preparation network, Kaplan, which was something like a cross between Damelin and UNISA.

When we returned to Washington in late 1992 from Pretoria, subscribing to daily home delivery of the paper was something one did just minutes after getting the phone, gas, electricity and water switched on in a new home. We added the Sunday edition of The New York Times as well, but that was something of an affectation, rather than a necessity for news.

But at almost the exact same moment, at work, and then a year or so later we started getting news via the Internet at home. Soon enough, many others joined in, so many that eventually The Post’s circulation fell to less than half its peak of 20 years earlier. The editorial staff dropped to about half the total working there at its height in the early 1990s. By 2013, the paper was barely showing a profit and revenue from the paper only accounted for about 15% of the overall revenue of The Washington Post Corporation, the holding company for all the various acquisitions that had been brought together under its umbrella.

With the paper’s financial fortunes continuing to ebb away, the current generation of the company’s family leadership – Donald Graham as CEO and Katherine Graham’s granddaughter Katherine Weymouth as publisher – quietly embarked on a mission to find a suitable white knight to take over the paper and save it as a viable publication. Ultimately they found Jeff Bezos, the now-legendary founder and owner of Amazon.com. Bezos purchased the paper for $250-million, using his personal fortune, rather than buying the paper as an acquisition for Amazon. This near-fire sale price echoes other recent sales of print newspapers such as The New York Times’ disposal of its New England holdings (inclusive of Boston Globe), at less than one-tenth of the price the paper paid for it years earlier.

So far Bezos says he does not plan to engage in day-to-day involvement in the paper’s management or editorial decisions, but that, of course, says nothing about how he will begin to reshape the paper’s position as a force in providing information to the nation – and the world. This is a world where the young (and, increasing, older people as well) continue to shrug off any routine reading of print copies of home-delivered newspapers, preferring to access the Internet and social media for their information instead. Making The Post’s task even tougher is the word on the street that in recent years it has lost its hold on the attention of the country’s political class (and everyone else who follows such things) to the impertinent Internet site Politico.

Of course Bezos has already said he is in this game for the long, long haul. If his new toy loses money in the early years of his ownership, why there’s always the cinematic example of the equally famous, but fictional, Charles Foster Kane who, when asked how he could continue to lose money with his new paper and stay solvent told his interlocutor, “You’re right, I did lose a million dollars last year. I expect to lose a million dollars this year. I expect to lose a million dollars next year. You know, Mr. Thatcher, at the rate of a million dollars a year, I’ll have to close this place in… 60 years.” If Bezos manages to lose a million bucks a year at The Post, well he will have to wait several hundred years before it makes a serious dent in his pocket. DM

Photo: Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein meeting with the Washington Post’s Publisher Katharine Graham, Managing Editor Howard Simons and Executive Editor Ben Bradlee during Watergate crisis. 1973. (Photo by Mark Godfrey)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider