Maverick Life

Racial hatred, racial hope: the science behind prejudice

Scientists tell us that racism isn’t hardwired, giving South Africans hope for reforming prejudicial bigotry. Could the painful history of a small, almost all-white US city called Duluth, and the science of how our minds acquire and process prejudice, hold clues to help South Africa re-engineer racists? MANDY DE WAAL investigates.

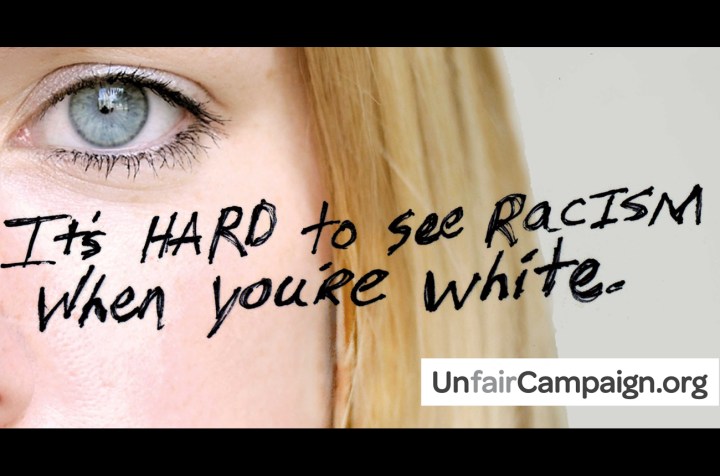

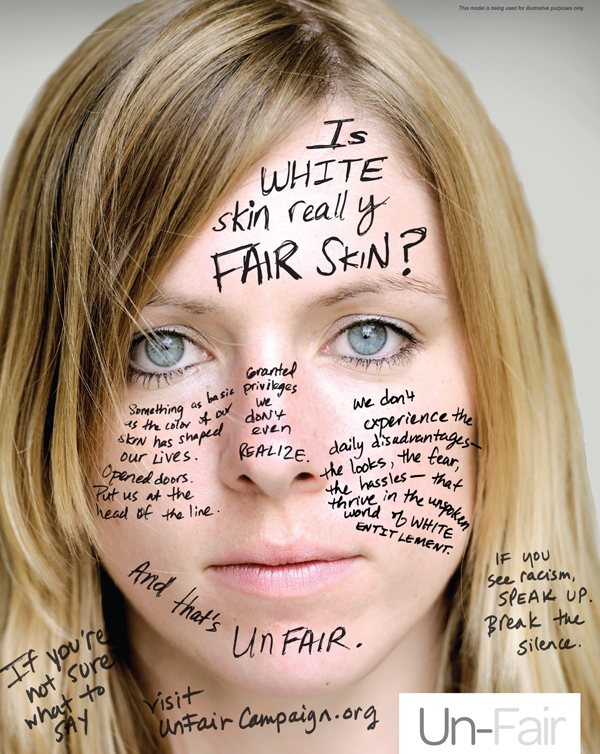

She has pale hair and piercing cornflower-blue eyes which stare right at you. But it’s the writing on her face that grabs your attention:

“Is white skin really fair skin? Something as basic as the colour of our skin has shaped our lives. Opened doors. Put us at the head of the line. Granted privileges we don’t even realise. We don’t experience the daily disadvantages – the looks, the fears, the hassles – that thrive in the unspoken world of white entitlement. And that’s unfair.”

The uncomfortable message is part of a campaign launched by the YWCA in the small port city of Duluth, Minnesota in the US. The uncomfortable question is aimed at raising awareness of white privilege and offering people in the city resources to re-engineer racism.

Photo: Duluth anti-racism campaign poster.

Like South Africa, Duluth in Minnesota has had its fair share of racial issues. Two years ago the University of Minnesota Duluth erupted in a furore when two white students made bigoted remarks about an African-American student after she walked into a lecture hall they were in. The race-based attack included references to the jungle and inferred blacks were “thieves”. Conversing on their Facebook wall, the girls said they felt “dirty” and “unsafe” in the black girl’s presence.

Less than two years later, civic organisations launched the anti-racism campaign to foster greater racial tolerance and understanding. “There was a citizen group that had been working on this in order to create a dialogue on race issues here in Duluth, and, you know, to create a conversation, a community conversation that was separate from a moment of crisis,” John Ness, the Mayor of Duluth told NPR.

“So often in our country, we only talk about race when there is some sort of controversy or a moment of crisis. And then the discussion gets blurred by focus on that crisis and gets us further away from really having an honest dialogue about race and race issues, and, in particular, white people’s role in addressing and being part of the solution.” The campaign had hardly been launched when a racist storm erupted yet again, this time at a men’s hockey match where students chanted racist jibes.

Duluth is pretty small in the population stakes, so one would think that racism there could be turned around fairly easily. Or, at least, more easily than in larger populations. The city has a population of fewer than 100,000 people, relative to Johannesburg’s four million. But its size has made no difference: Duluth is a city of inequality, forged on bloodshed and prejudice.

On the evening of 14 June 1920 two teenagers, 19-year-old Irene Tusken and 18-year-old James Sullivan, went to see a travelling circus in town. After the show, the pair stayed on to watch the big top being disassembled.

The facts of what happened next are undetermined. What’s certain is that Tusken claimed she was sexually assaulted and in the early hours of 15 June, 1920, Duluth police detained six black youths employed by the circus and charged them with rape. The arrests followed a lengthy identification parade of way over 100 black men, during which police forced Tusken to select her rapists.

Tusken struggled initially because she couldn’t recognise the faces of her assailants, but after much goading, the six were picked and imprisoned. News of the arrests spread quickly and by that evening a huge mob had amassed outside the prison.

“The dozen or so officers who tried to protect the prisoners were almost powerless; the city’s police commissioner had ordered them not to fire on the crowd,” the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported years later. “The officers fought hard with nightsticks, fists and fire hoses, but several were injured and the mob prevailed.”

The mob broke down the jail doors and windows using timber, bricks and rail tracks. A vigilante-styled court was rapidly established, the six were tried, and three were found guilty. Their names were Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie.

“One by one, they were dragged a block uphill to a lamppost. Eloquent pleas from a police lieutenant, a judge and a Catholic priest — who climbed the pole to address the crowd – failed to sway those in the crowd from their purpose,” the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported.

Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie were savagely beaten. After that they were hung by their necks from the telephone pole. Isaac McGhie was 20 years old, Elmer Jackson and Elias Clayton just 19.

After the incident, three men were convicted of rioting and went on to serve prison sentences of less than two years. No one was charged with murder. A doctor who examined Tusken found no evidence of rape. The young man who accompanied Tusken to the circus accompanied her home, not saying a word to her parents.

Lynchings were common during that time, particularly in the more conservative southern and mid-western states. Between 1889 and 1918 at least 3,224 people were lynched in the US. Some 70% of those people were black, in a country where – unlike South Africa – black citizens are in the minority. Duluth in particular is a predominantly white city: according to the last census, over 90% of the city was white and just 2% was black. There’s a strong European and the population’s ancestry is predominantly German, Norwegian, Swedish and Irish.

The story of the lynchings died down for a while, but was resurrected by culture in later decades. In the mid-sixties Bob Dylan is said to have penned “Desolation Row” about the Duluth hangings. A photo of the bodies of Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie strung from that pole was taken and turned into a postcard.

Dylan, who grew up in Duluth, opens his lyrics with the phrase: “They’re selling postcards of the hanging,” and continues: “The circus is in town. Here comes the blind commissioner, they’ve got him in a trance. One hand tied to the tight rope walker, the other is in his pants. And the riot squad they’re restless, they’ve got nowhere to go.”

And the story didn’t just haunt music, photography, postcards; it made its way into literature too. After the killing , a Duluthian made a statement about the lynching that would be later be immortalised in the title of a book written by Michael Fedo. The utterance and the name of the book? They was just Niggers.

Todd Nelson, professor at California State University and author of The Psychology of Prejudice, specialises in the research of bigotry and stereotypes. He believes humans are not hardwired to hate.

Photo: Todd Nelson

“In human beings, thoughts, emotions, and behaviours are shaped by human-made meaning systems that must be taught, learned, and mastered,” writes Nelson. “Social conditioning has merged with neurobiologically-based survival instincts to produce the majority of our more complex contemporary prejudices. The social and cognitive developmental literature has shown that children demonstrate clear ethnic and racial awareness at around three or four years of age. Differences are never the problem to children. It is the teaching of prejudicial attributions and misattributions to differences that foster eventual conflicts.”

Nelson writes that many racial biases are taught, and that it is often the most prejudiced individuals who have little, if any, interaction with the target of their racial animosity. Nelson quotes Larry King’s book Confessions of a White Racist, which describes the frequency of the bigotry King heard as a child.

King writes: “Quite without knowing how I came by the gift, and in a complete absence of even the slightest contact with black people, I assimilated certain absolutes: the Negro would steal anything lying around loose and a high percentage of all that was bolted down; you couldn’t hurt him if you hit him on the head with a tire tool; he revered watermelon above all other fruits of the vine; he had a mule’s determination not to work unless driven or led to it.”

“Growing up on a heavy diet of derogatory racial statements of this nature creates the negative frame necessary for destructive misattributions to thrive,” writes Nelson. “The ‘rule of nine’ theory postulates that seeing or hearing the same information more than nine times cements that notion into the mind as a lasting image or relationship.”

Decades of bigoted distortions and social reinforcement create a prejudiced state of mind. “Worst of all, in some communities, espousing sentiments outside of the bigoted boundaries seldom goes unpunished. Prejudices get passed along from one generation to the next as effortlessly as genetic background is transmitted, but the targets of our hatred often become the focus of our greatest fears. When anxiety and hatred become cyclically intertwined, human beings sometimes begin a mental rollercoaster ride from which it is difficult to comfortably disembark.”

This is confounded by biological function and an anger response that limits a person’s capacity to think clearly, to try and understand or explore better options for response, or to construct intelligent solutions. Nelson writes that the higher faculties are “all significantly compromised due to change in physiology and changes in the brain” during states of anger.

And because the brain makes no distinction between emotional, physical, intellectual, socio-cultural, psychological, or moral threats the response is one of primitive emotion.

The central question, though, is whether racism can be reversed. Nelson believes it is a matter of continual awareness which address class and race issues, and the long-term psychological and emotional damage they wreak. He says this calls for deep and honest conversations that linger on psychological devaluation of not only those who are “victimised” but also those who damage themselves by doing the victimising.

“A mind that can suspend feelings of empathy and morality for one’s fellow man, or one that does not generate the requisite levels of compassion and cognitive dissonance necessary to interrupt extreme prejudice and injustice from residing comfortably with an abundance of visual, constitutional, moral, and religious contradictions, is a mind that cannot be deemed healthy by the most generous of psychological standards,” writes Nelson.

Like the lynchings of Duluth, history shows time and again how racial or ethnic hatred reduces humans to the most abhorrent behaviours. “A full and honest portrait of those groups guilty of man’s inhumanity against man, as well as human injustices and genocide, would portray a mosaic of humankind around the globe. As broad collective groups, we cannot be distinguished as all good or all evil, as all intelligent or dull, any more than we can be identified racially as 100 per cent kind or unkind,” Nelson writes.

What people can immediately do to try to re-engineer prejudice is to practice Nelson’s ten strategies – The Ten Strategies for Reducing Prejudice (included below). These are aimed at stemming the downward spiral towards racism and can be posted in schools, universities and, of course, on social media.

In South Africa, where racism regularly surfaces, the tendency on social networks is to form a lynch mob. To punish, to exclude and to shame. Perhaps there’s a lesson to be learnt in Minnesota.

Duluth’s anti-racism campaign is controversial, but it is aimed at promoting frank dialogue, which is positive. Similarly Nelson’s strategies and insights on the psychology of prejudice offer good insight. Having the courage to open ourselves to honest debate without shaming or recriminating people is a step forward. Understanding the very nature of our minds and racism surely another.

There are many ways to tackle racism, but what’s certain is that we need a smarter response than the one we’ve marshalled to date if we seriously want to change mental attitudes to race in this country.

We exponentially add to the quality of life when we focus on all of the ways in which we are all the same, rather than those few superficial ways in which we are different. Love, security, and a sense of hope bind humankind together. DM

Ten Strategies for Reducing Prejudice in the School

By Kenneth Wesson

Ours is not a colour-blind society. Noticing physical differences is a natural aspect of our visual experience. Placing a negative frame around those differences fosters prejudice. Schools can play an important role in teaching students to celebrate “proversity,” our shared human commonalities. We are all 99 per cent alike.

- Avoid convenient all-group categorizations. They always have built-in biases. Equating personal traits or behaviours to physical differences is always erroneous.

- Plan more interactions with people from diverse racial and social groups. Volunteer to work in inter-group settings where common goals are pursued with room for making new friends.

- Take pride in your achievements, not in your skin colour. Every person becomes part of a race through no personal effort of his or her own. Taking advantage of privileges that your race unfairly enjoys over others reinforces past prejudices.

- Carefully evaluate all assumptions. We cannot assume that every member of a group is alike based on one common characteristic. Members of the same family are quite different, so why would you expect the members of an entire race to be alike?

- Always give yourself plenty of time for thorough and rational information processing. When decision-making is hurried, your best thinking will be compromised.

- Pursue opportunities to learn about the historical, psychological, and existential consequences of human prejudices. Read about and discuss the lives of admirable individuals who overcame the obstacle of prejudice and discrimination.

- Intelligently analyse events and information, including TV content. The biases and prejudices sponsor misjudgements. TV panders to stereotypes because simplicity makes television programs easier to follow and understand. Reduce exposure to any information resources that rely heavily on prejudices and stereotypes to entertain. (If you see it often enough, eventually you will believe it.)

- If “feeling good” requires putting down others, then you need to find another way to bolster your self-esteem. Hurting others is a sign that counselling interventions are needed.

- Prejudice, hatred, and violence are never solutions to problems.

- Remember, you can’t choose up sides on a round planet. We’re all on the same side. Let’s show it every day and at every opportunity.

Read more:

- Simply condemning racism is only half the battle by Mmusi Maimane in Sunday Independent;

- Reconciliation requires open eyes, open hearts by Lindiwe Mazibuko in City Press;

- Heads roll as racism boils over on Facebook and Twitter in Mail & Guardian;

- Racism still rules in adverts in Mail & Guardian;

- This is your brain on racism. Or is that liberal guilt? in Discover Magazine.

Main photo: Duluth campaign.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider