Media

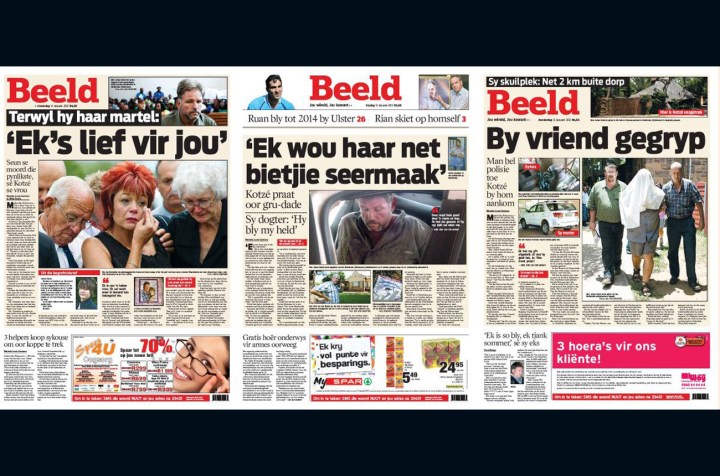

Beeld, Modimolle and a cruel & unusual case of violence

The media have had a field day with the Modimolle murder and rape story, which has eaten up headlines because of the violent and bizarre nature of the crimes. It’s big news but just how much gory detail is in the public interest and should the media be publishing photographs of minors motivated by “the public interest”? MANDY DE WAAL investigates.

Beeld’s photograph of Angelique Bonnette shows the 16-year-old sister of Conrad Bonnette standing next to his grave, her face grief stricken. In her hand a blue handkerchief. She’s using it to wipe the tears from her swollen, red eyes.

On 4 January 2012 the small Limpopo town of Modimolle, formerly known as Nylstroom, was rocked when unspeakable horror was meted on Ina Bonnette and her son, Conrad. Ina Bonnette was allegedly gang-raped and mutilated in a cruel and unusual attack, allegedly orchestrated by her estranged lover, Johan Kotze. It is alleged that Kotze shot Bonnette’s son, Conrad, three times, eventually killing him, but not before the young student had begged for his life.

The nature of the attack was so sadistically gruesome and simultaneously bizarre that it was massive news, and played out in the headlines of South Africa’s media. But the media would also help find Kotze, who was on the run, by publishing photographs of the alleged murderer. A week after the gang rape and murder, the man the media has dubbed the “Modimolle monster” was apprehended. A few days later Conrad Bonnette was laid to rest.

Modimolle is a quiet, unremarkable town that lost its Afrikaner name in 2002 to a Tswana word taken from the phrase “modimo o lle” that literally means “God has eaten”. But in a “man bites dog moment”, Modimolle has been thrust into our national psyches thanks to the alleged brutal actions of Johan Kotze.

The story is every editor’s dream, and nightmare. In a world where reality television and tabloid news has delivered a voyeuristic audience with a strong appetite for gore porn, the Modimolle story is a news jackpot. It’s news that delivers reams of possible headlines, miles of grisly minutiae, an ongoing breaking story and a victim that didn’t recoil from the media.

The nightmare – the press code would have us believe – is that news editors sweat the decision of what to publish or what not to publish. And so it is that iMaverick is in conversation with Pieter du Toit, news editor of Beeld, to find out exactly why that paper decided to use a photograph of 16-year-old Angelique Bonnette and why this was deemed to be in the public interest.

Section 9.2 of the South African Press Code reads: “Exceptional care and consideration must be exercised when reporting on matters where children under the age of 18 are involved. If there is any chance that coverage might cause harm of any kind to a child, he or she should not be interviewed, photographed or identified unless a custodial parent or similarly responsible adult consents or a public interest is evident.”

iMaverick: “Was Ina Bonnette’s permission obtained for taking photographs, and was her permission expressly obtained to use her child’s photograph? Did you get informed consent?”

Pieter du Toit: “It was a very difficult story to cover. It was a unique story in that we are all painfully aware of legal prescripts related to rape victims, and victims of sexual assault. In this instance it was a woman that was raped allegedly by three people set up by her husband, so that was a difficult thing. The police sent out identikits asking for the public’s assistance to try to get hold of Johan Kotze. Strictly speaking, you are not allowed to identify Johan Kotze, because you are then identifying Ina Bonnette by implication. At Beeld what we did was to bypass each story past our legal counsel. Ina Bonnette gave us explicit permission to identify her, and by implication identify the rest of her family.”

Beeld’s news editor neatly skirts the direct question, and so it is put to him again. “Did you get express permission to use the photograph of her (Ina Bonnette’s) daughter?”

Du Toit: Standing at an open grave in public? That would be the picture we used on page four on Saturday? Uh… Uh… When publishing a picture like that it is a difficult decision to make, and it isn’t my decision to make. It is a decision that is made by an editor on duty at night. As you well know it is not a black and white issue. It is a difficult decision to take. You always have to take cognisance of the interests of all concerned.”

The question has still not been answered to use her child’s photograph, so iMaverick puts it to Du Toit again, this time marginally reframed: “How do you decide what is in the public interest given you must weigh the family’s, and the minor’s, right to privacy with what is in the public interest. How do you do that?”

Du Toit: “It is a story that generated massive public interest because it was a pretty bad crime story. It was out of the ordinary and I think the crucial thing was the consent by the rape victim who herself gave us permission to identify her, to interview her, and to publish details she gave us. There were a lot of grim details that didn’t come out that we decided not to publish. We, in our editorial meetings, decided it would not be in the public interest to give those details.”

“It is a decision you take on a case by case basis, there aren’t any fixed or hard rules. It comes down to the personal relationships between the journalists covering the story and the family, who are the subjects of a tragedy like this. In this instance, our reporter was on the scene very quickly and worked very closely with the police, and I would in all honesty say we covered the story in a fair manner.”

Du Toit is still side stepping the question regarding permission, so it is time to be a little more blunt. iMaverick asks: “Did you expressly ask Ina Bonnette for the use of the photograph of her daughter who is a minor as required by the Press Code?”

Du Toit: “Where does it say we need to ask permission?”

iMaverick: “It is stated in Section 9.2 of the Press Code. Are you aware that the press code was recently updated?”

Du Toit scurries to find the press code. Reads it aloud, but instead of answering a direct question that’s been put to him three times now, starts asking his own questions: “What is the potential harm that might be caused by publishing that picture?” he asks.

Media Monitoring Africa’s William Bird has the answer. Bird believes the use of an image of a grieving Angelique Bonnette is particularly unethical if not opportunistic. “She’s a minor and that photograph was particularly invasive,” Bird says. “While strictly speaking it may not violate the press code because Beeld could offer a public interest defence, it is incredibly intrusive and isn’t appropriate. This child is suffering in what is clearly a particularly private moment of trauma and grief. What purpose has the use of that photograph served? Does it legitimately serve the public interest, or is it purely being used to sell newspapers?” Bird asks, adding that the Afrikaans daily’s graphic descriptions of violence in the Modimolle case were particularly gratuitous.

“Short of showing us images of the woman’s genitals, Beeld just about told us absolutely everything. The paper’s coverage was graphic and unnecessarily so.” Bird says the paper suggested Ina Bonnette had been sodomised and didn’t hold back from lingering on the gruesome minutiae of the attack. “When there’s that level of extreme detail, what legitimate public interest is served given the press is dealing with a woman experiencing severe trauma?”

Bird questions whether Beeld got informed consent for the interview and photographs from Ina Bonnette, which he explains is very different from common-or-garden consent. “If you have a victim that’s just been through a horrific, violent rape you can’t just walk in and say: “Hi, I’m a journalist from Beeld, now tell me what they did to you?” that is mere consent. Informed consent is ensuring the person is in clear and sound mind, understand who you are, and fully understands the consequences of what giving you permission means.”

“It is one thing to harass a person in public office,” says Bird. “But it is another to take an ordinary private citizen at a time when they are so clearly traumatised, and to use that moment to choose to ask them for an interview and photographs.”

Bird says this kind of unethical media behaviour plays straight into the hands of an ANC that wants to gag the media in general, but newspapers in particular. “Beeld would struggle to say that they are adhering to the highest ethical standards in this case. The paper’s journalists have done exceptionally good work in the past, but in this case the treatment of this story adds little value to journalism in South Africa.

Just over three years ago, Media Monitoring Africa did a research paper on Beeld’s coverage of violence called “Crime according to Beeld: Fear in Black and White.”

For the purposes of the study, the researchers monitored coverage in Beeld for a month. In terms of the findings for the period:

- Beeld frequently showed the subjects of crime as victims, while photographs of child victims predominated. “In some incidents, there is reason to doubt whether the pictures were taken with permission,” the report reads.

- When it comes to violence, the report points out that Beeld is partial to bloody, emotive language. Words like “hartseer” (grief), “koelbloedig” (cold-blooded) and “huil” (crying) are frequently used, while a good chunk of articles detailed the bloodiness of events. Headlines were also shown to be overly dramatic.

- During the review period, Beeld frequently violated ethical and legal guidelines for the coverage of children.

Beeld comes under regular fire from Media Monitoring Africa. In August 2011 they were slated for violating the dignity and privacy of grieving children and their families; while the year before the media advocacy group declared Beeld had violated children’s rights and sensationalised violence by children.

“If you only read Beeld in this country, you get this sense that you are under attack. That there is a high likelihood that your personal safety is at risk in South Africa,” Bird adds. Beeld’s Du Toit doesn’t deny that the Modimolle story helped the press sell papers, but says the reporting on the Johan Kotze case was done “in the best traditions of journalism.”

“We are a commercial enterprise and the commercial imperative is always there, but you need to weigh this up with careful and sensitive reporting, especially in cases like this,” says Du Toit. “I would disagree with critics who say we sensationalised the story. We gave the story prominence because the people and the story fell squarely in our newspaper’s target market. If something happens in the market we serve, in this case the Afrikaans speaking market, we need to cover the story from all sides as thoroughly as we can.”

The news editor says aggressive editorial meetings are held, and thorough debate decides what’s news and in the public interest, and what falls outside of those parameters. “It is a very difficult decision once you have all the gory details, and once you have the specifics around the assault. The question you ask is: “Is it in the public interest that we publish this?” Some argue: “Yes, because we need to show the gruesomeness of the assault to give context to why we are giving such prominence to the story.” The other argument: “Is it in good taste to publish a story with very upsetting details about an assault?” It is a difficult decision that is not taken lightly by our or any other newspaper.”

SA’s Press Ombudsman, Joe Thloloe, told iMaverick he wouldn’t comment directly on the Johan Kotze coverage in Beeld, nor the use of Angelique Bonnette’s photograph. “You are putting me in a very tight spot because the matter may still come before me and then I may have prejudged it,” ventured Thloloe. But he did volunteer advice in the form of questions editors and news editors must ask themselves before taking a decision on graphic coverage. “The questions that need be asked are: why is it necessary to use this picture? Why is it necessary for the reader to see this picture? If you cannot find any valid answer to these questions then you don’t use the photograph.”

Sanef’s Raymond Louw, says that at the end of the day, it’s a matter of subjective opinion. “One newspaper editor may decide to use this (the photograph of the grieving minor), but another newspaper editor may decide no, because it is an intrusion on a child’s grief and that this is unacceptable. It is almost a very personal decision by an editor.”

“Some people will accuse those newspapers of printing pictures purely to gain circulation and only considering the financial imperative, but this is an extremely horrific crime and all the facets of it should be made available to the public. It is in the public interest to see the full extent of the damage that was done, but that said, deciding whether to publish or withhold is probably the most difficult decision an editor must make,” says Louw.

But let’s get back to the question of whether or not Beeld got express permission for that photograph of Angelique Bonnette to be used. Asked for the fourth time, Du Toit says: “I believe that we covered the story fairly. We were in contact with the whole of the family including the father and the minor child. We were always upfront and clear when we spoke to them about what it was for. They never had any doubts, and we haven’t received any complaints about the coverage, least of all from the family.”

But even if Beeld didn’t get express permission to use that photograph, the paper could merely argue that the photograph (and attendant stories in all their gory detail) is in the public interest. After all, in South Africa, what’s in the public interest is merely a matter of an editor’s personal opinion, and apparently fairly easy to justify. DM

Read more:

- Kotzé: Child of God or ‘5-star, sadistic psychopath’? in Mail & Guardian;

- Fear and loathing at Beeld in Daily Maverick.

Resources:

- The DART Centre for Journalism & Trama.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider