NATURAL WORLD

The trouble with shooting stars

You get Earth rocks and moon rocks and Mars rocks. Then there are deep-space rocks whose age boggles the mind. But who owns them?

There were parallels, naturally. But for Tintin and his dog, Snowy, the day ended as hot as… well… blue blistering barnacles. For me it was cold and rainy.

We were both, it turns out, awed by a fiery object that had fallen from space. In Hergé’s comic, Shooting Star, Tintin’s meteorite fell into the North Sea with a deafening boom, melting tar and wilting startled citizens on the way. Mine was planted in my hand one wet evening by University of the Free State geologist Professor Duncan Miller.

The cover of Hergé’s ‘Tintin, The Shooting Star’ (Image Don Pinnock)

A page from Hergé’s ‘Tintin, The Shooting Star’ (Image Don Pinnock)

As he did so, Duncan cleared his throat and did the dramatic: “That’s the oldest object ever held by a human being. At 4,56 billion years it predates any Earth rocks. It was formed in the solar nebula that gave birth to our planets.”

I boggled at the lump, which suddenly seemed heavy with portent.

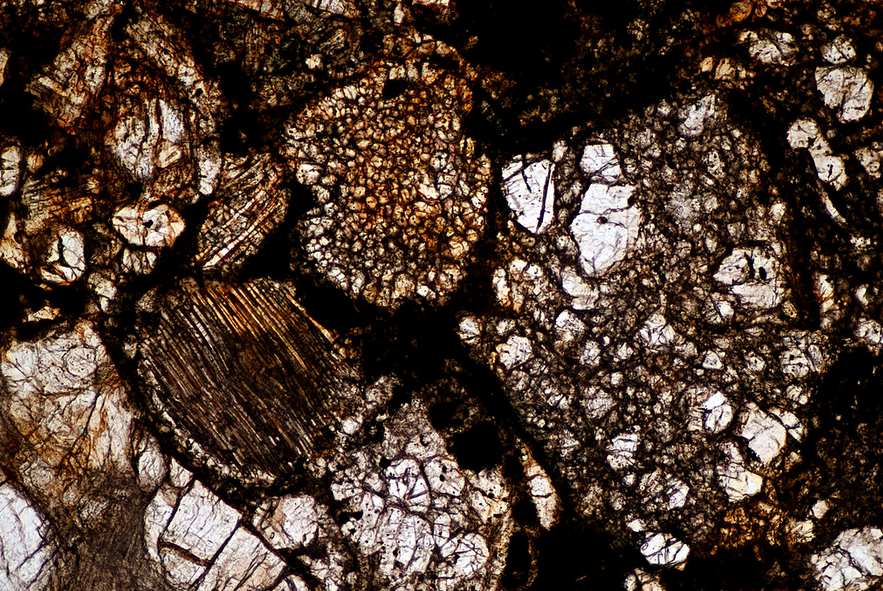

“If you look at the polished surface,” he continued, knowing he’d hooked me, “you’ll see little spots, about half a millimetre across. They’re chondrules – space dust from supernovas, star-death explosions, captured in the meteorite. The rock looks like nothing. But you must admit it’s… evocative.”

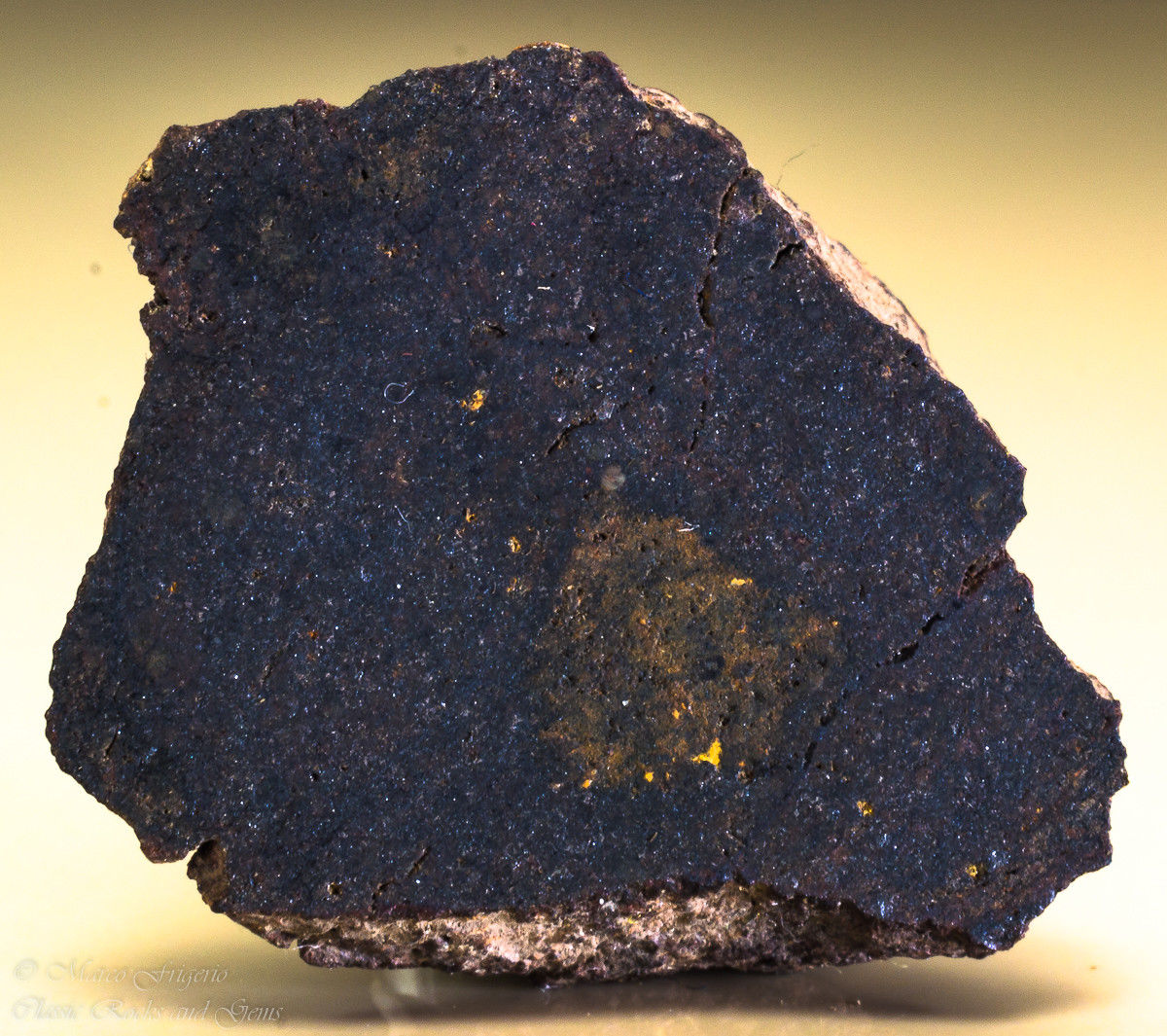

That was my introduction to Korra Korrabes, a 22kg chondrite meteorite discovered in Namibia where it was helping to prop up a wall. It’s a magical thing – quite as spectacular as Tintin’s shooting star – and a lens into time so deep it makes all recorded history seem like the brief flick of a butterfly’s wing.

The space rock was tracked down by a Tintinesque meteorite hunter who probably required less whiskey than Tintin’s friend, Captain Haddock, and a good deal more knowledge. For reasons mysterious, he wished to remain anonymous.

Exactly why Korra Korrabes had been floating around for billions of years requires a rather circuitous explanation.

Stars are elemental cookers and they’ve been at it for a long time. The Big Bang produced only hydrogen, helium and lithium-7, great clouds of which, through gravitational attraction, whirled together and ignited to give birth to huge, unstable stars.

In their hearts, oxygen and carbon were produced, and when these stars exploded – as most stars eventually do – they ejected gas and dust across space. This eventually formed daughter stars which brewed up still newer, ever heavier, elements.

By the time our sun was formed, 4,5 billion years ago, generations of stars had been succeeding one another for around 10 billion years. By then there were nearly 100 elements to choose from – a very good soup in which to spark life.

The real star performers, however, are supernovas. When the hydrogen of a massive star – maybe 10 times the size of the sun – is used up, it collapses. Under unthinkable gravitational forces atoms are crushed to a hard neutron core which suddenly halts the collapse. The effect is like a jet of water hitting a brick wall. The rebound causes a massive explosion which ejects the outer layers of the star, producing an immense shockwave. The flash can outshine an entire galaxy.

This wave, passing through the hurtling material of the dying star, causes what is described as nucleosynthesis, creating new elements and causing them to merge and condense to form sand-sized droplets of matter. These are the seeds of new stars.

How we know this is described rather well by comic-book Tintin’s Professor Phostle: “You’ve heard of the spectroscope? It’s the instrument that breaks up light and enables us to discover elements in stars, elements not yet isolated here on Earth. Each of these lines is characteristic of a metal. These lines in the centre represent an unknown metal which exists in the meteor… ”

In galactic terms our local star, the sun, is a mere speck. If you filled a fair-sized cathedral with rice grains it would give you an approximation of the number of stars in the Milky Way. To get their distribution proportionally right, you’d have to scatter them from Earth to the moon.

The sun was formed by space dust which spiralled as it fell inwards. This left a disc of circling matter – dust, ice-encrusted comets, asteroids and larger “planetesimals” – millions of which collided with each other, eventually forming planets.

The Earth itself, comparatively speaking, is mere stardust. While the sun makes up something like 99,8% of the solar system’s mass and Jupiter two-thirds of what’s left, Earth weighs in at around 0,05% – basically leftover material.

Cross section of Korra Korrabes. Image: Supplied

However, not all the matter was claimed in the great spiral dust-gathering. Between Mars and Jupiter is a dangerous, swarming asteroid belt and out beyond Jupiter there’s a strange zone known as the Oort Cloud, consisting of billions of restless comets – affectionately referred to by astronomers as cosmic snowballs.

There are basically three sources of meteorites: ancient accumulations of stardust, the iron cores and rocky crusts of asteroids or destroyed planets, and chunks ejected into space from other planets or the moon by meteorite impact.

They rain down on Earth in astounding numbers. It’s estimated that around 100 tons a day hit the upper atmosphere, generally as space dust. Most meteorites explode when they encounter the atmosphere, but some are big enough not to be vaporised. Most splash into the oceans – which cover two-thirds of the planet – but occasionally they make the news.

In 1911 a meteorite killed a dog in Egypt, in 1991 a roof in Japan was holed and in 1992 a meteorite slammed through the boot of a car in Kentucky, New Jersey. In 1994 one thumped through the roof of a warehouse in George. More recently a herder in Namibia was hit on the head by a chunk which first bounced off the branch of a tree, and a girl in North Yorkshire was struck on the foot by a small space rock.

Generally, meteorites aren’t troublesome, but there’s a lot of stuff flying round up there, some of it frighteningly big. The Shoemaker-Levy#9 comet, which hit Jupiter in July 1994, left an impact shockwave the size of Earth in the giant planet.

There’s also strong evidence that the moon was created from flying debris when Earth collided with an object about the size of Mars somewhere around four billion years ago. This Big Splat re-melted and thinned Earth’s crust, tilted the planet and increased its spin speed, giving us a short (in planetary terms) 24-hour day.

Another “splat” could have led to the demise of the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago when a space object is thought to have hammered a 200km diameter crater into Yucatan province in Mexico. Dust from the impact and smoke from runaway forest fires would have blanketed Earth, preventing photosynthesis and killing off giant herbivores and their toothy predators.

On average, a collision between Earth and a big meteorite or comet seems to occur about every 100,000 years. We’re a little overdue.

If this seems to be a long, wild ramble, it’s the only way to describe Korra Korrabes. The scrap of meteorite in my hand was a grainy amalgam of captured ancient supernova dust.

Meteorites look much like ordinary rocks and generally only experts can recognise them. But in deserts like the Namib or on the icefields of Antarctica they’re out of character and easier to spot, which is why these areas attracted meteorite hunters.

Herein lies the problem. To astrophysicists, meteorites are dipsticks into deep time and a potential source of new and exciting elements. For collectors they’re fascinating treasures. Kilo for kilo, some types of meteorite are far more rare than almost any precious mineral on Earth. This has ensured some of them have a high price tag.

Meteorites are damnably hard to find. If you were to traverse, say, every 2,5m square on a 10km2 site you’d have to walk 20,000km.

There are marketing sites on the web with names from seriously scientific to pure whimsical: International Meteorite Brokerage, Southwest Meteorite Laboratory, Meteorite.com, Cosmic Matter, Dinocom…

“Whether it’s your first meteorite purchase or you’re looking for that extraordinary show piece,” coos Meteorite.com, “these fine dealers are here to serve you!”

With a growing market for space objects, there’s little doubt market forces are leading to theft of meteorites from museums and possibly from university collections. On www.meteorite.com are some sad appeals for lost or stolen rocks:

Arkansas Planetarium: “We have a missing Mundrabilla meteorite. If someone should contact you from Arkansas with a meteorite for sale, would you please work with us on it? Thanks.”

Transvaal Museum: “The only known sample of the Namibian Itzawisis pallasite has disappeared from the collection. This meteorite is of profound interest to a research programme being run at the University of Cape Town, and we beg anyone with information about it to please contact us urgently.”

American Meteorite Survey: “A 444,5-gram complete slice of Glorieta Mountain meteorite was lifted at the Tucson Show. This is a very valuable piece.”

Casper Meteorites: “Our 0,016-gram slice of lunar meteorite DAG 400 has been stolen.”

In South Africa and Namibia ownership of meteorites found in those countries is effectively illegal for private collectors.

“My position,” commented Mary Leslie of the South African Heritage Resources Agency, “is that legislation disallows private ownership of meteorites as they are considered to provide information on cosmic matters which all people need to be able to share in.”

Korra cross section. Image: Supplied

Head of the Namibian Geological Survey, Gabi Schneider, had much the same view: “The Monuments Council will not issue a permit to a private collector, since this rare material should not be on someone’s coffee table, but rather available for science and education.”

Not all scientists agree. Marian Tredoux of UCT’s Department of Geological Sciences considers such legislation to be a death warrant for meteorite research. “Most people won’t come forward with their samples, nor go to find others, if they fear the state will take them away without reward.”

Duncan Miller considers the South African and Namibian laws to be flawed: “In reality, they’re unimplementable. No customs officer would be able to distinguish between a meteorite and an innocuous stone or lump of rusty iron. The result is that collectors can smuggle meteorites out of the country with ease.”

A South African meteorite dealer, who asked not to be named, said nobody was going to hand in a meteorite to the state when there was no incentive and they could sell it overseas. The legislation just scared them away.

“The law should encourage people to find meteorites and also make them accessible to science and the state,” he said. “My suggestion is that they should be handed to an academic institution for classification, then half should be handed back to the finder with a certificate of authenticity allowing them to keep or sell it. That way the state gains a meteorite and the finder has value added to their treasure.”

Tintin, of course, found his treasure in true adventurer style with no messy paperwork. He parachuted onto the teetering meteorite and leapt off as it sank, clinging to a precious lump of the stuff wrapped in a flag. He returned home, of course, to a hero’s welcome.

Snowy, on the other hand, merely got himself into nasty scrapes and wondered why there was so much fuss about a silly rock. Until Duncan Miller parked a 4,56-billion-year-old space rock in my hand, I would have voted with Snowy. DM/ML

A wonderful read…like a good meal,it has a peppering of Humour, a base of science and enough questions to make you want to come back for more!

Thank you.

Tks Don. Enjoyable read. Apart from the meteorite you held in your hand, spare a thought for Earth itself. In essence the meteorite is only 0,06 million years older than Earth which we all are custodians of. And being such a tiny fraction of another spec in the Universe, and with no proof yet that there is life anywhere else, Earth is quite a unique piece of stardust too.

Well billions of blue blistering boiled and barbecued barnacles!

Sentience about samples of sizzling speckles of stardust and shooting stars for survival of all species under the Sun.