MAVERICK CITIZEN

How did a class of potentially dangerous chemicals manufactured in the US, get to the Hartbeespoort Dam? And if they got there, where else are they?

Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals are everywhere. Several studies over the past decade show that PFAS are in our water, animals, plants and ecosystems, and, worryingly, they are in almost every province. This is Part Two in a four-part series.

Read Part One here.

The only study (that this journalist could find) which reflects the presence of polyfluoroalkyl chemicals (PFAS) in humans in South Africa was conducted more than a decade ago.

In 2010, a study found the presence of PFAS in the maternal serum and cord blood of a sample of South African women in the Western Cape, Gauteng, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal, with perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) the most abundant, followed by perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).

The PFOS levels found were lower than those found in industrialised countries, and the PFOA was similar to concentrations found in other countries. Remember that these chemicals are linked to birth defects, so this finding should have sparked major concern among health officials. It didn’t.

Though the studies on humans are limited, a raft of studies have shown the presence of PFAS elsewhere.

In 2011, a study found PFOS in fish from Boegoeberg Dam (Northern Cape) and Rooipoort Dam (Free State), something the report describes as a “surprising distribution”.

The authors suggest “the pattern we see might be due to past use whereby residues have now found their way downstream, or it reflects local use of unknown source… the reasons for this distribution pattern need further investigation.”

It also found PFOS in birds’ eggs at Bloemhof Dam and Barberspan, neither of which are near industrial areas. The Bloemhof Dam in North West supports more than 250 species of birdlife and lies at the confluence of the Vaal and Vet rivers. It is a popular angling destination.

Remember, these chemicals bioaccumulate. An animal (or person) who eats PFAS contaminated food absorbs these chemicals.

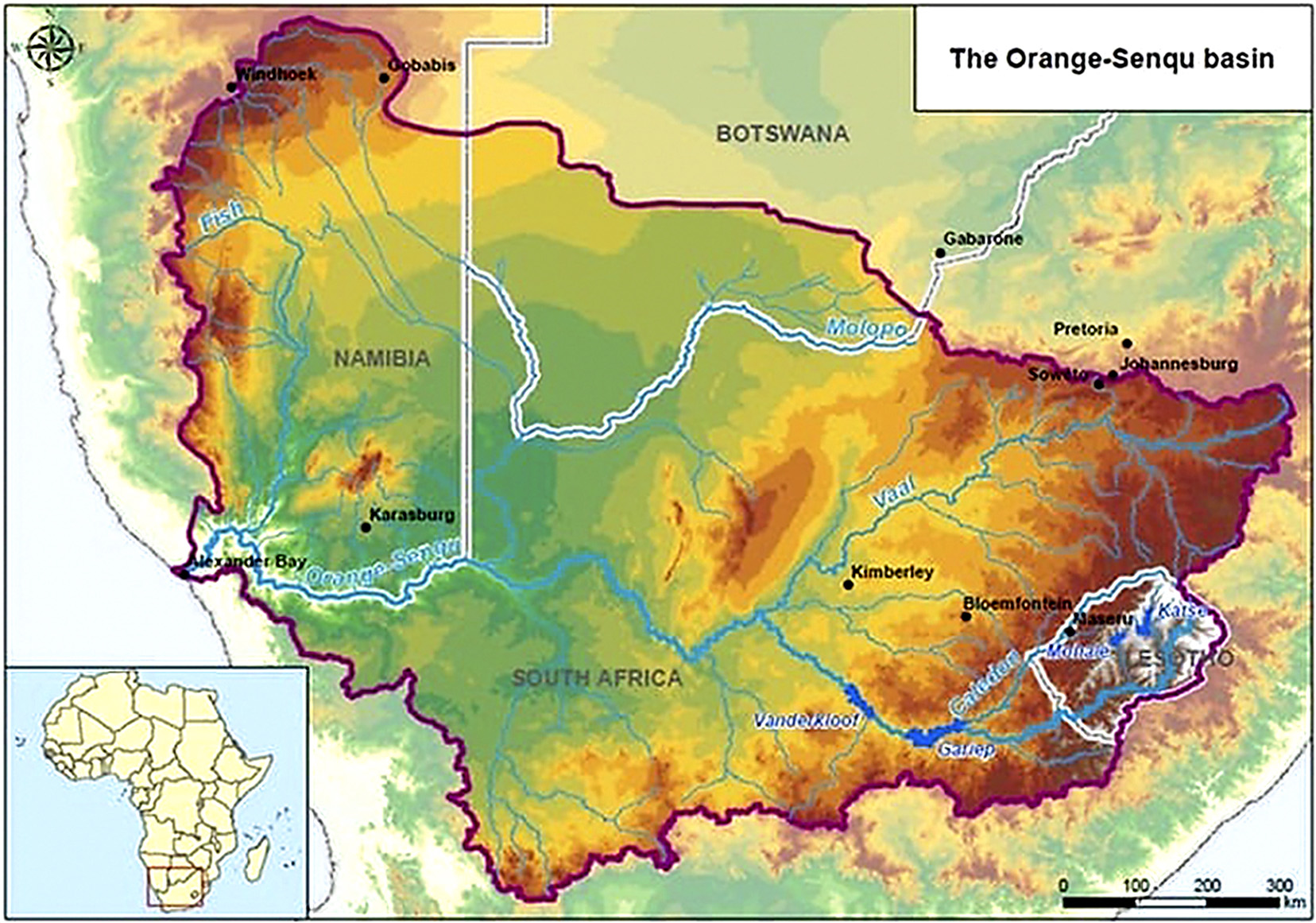

High levels of Per-and Polyfluroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been found in the Orange-Senqu basin. The levels of PFAS were some of the highest ever found in biota anywhere in the world. (Photo: infrastructurenews.co.za / Google)

In 2014, a follow-up to the 2011 study reported that “the very high levels of PFOS found in bird eggs in the centre of the Orange-Senqu river system were not expected… the levels found… were some of the highest ever found in biota anywhere in the world” (my emphasis).

In addition, the report noted that human consumption of PFOS via fish should be seen as a serious concern. The 2014 research found that PFOS was not originating from mines, as they had originally hypothesised, and that the high concentrations in bird eggs were confounding because the water they measured did not contain PFOS.

“Apportionment of sources is very difficult without good clues and very expensive research,” says Prof Henk Bouwman, author of the study and Professor of Zoology at North West University.

“We could not find a particular source, but we only had a limited search. How there were such high concentrations in birds’ eggs from Bloemhof Dam remains a mystery. It may be that over decades of use and releases, it washed downstream and somehow got stuck behind the dam wall. The mechanism remains unknown.”

In 2014, PFOA and PFOS were found in river sediments in the Western Cape (Salt River, Diep River, Eerste River) and the research found that “some of these concentrations are higher than those previously reported in similar studies in various countries; this suggests there is cause for concern”, and that “the prevalence of PFOS and PFOA in sediment samples from rivers from which irrigation water is sourced for agricultural purposes indicates a risk of agricultural produce contamination” (my emphasis).

What’s in our agriculture, will eventually be in us.

In 2014, PFOS was found in crocodile eggs in the Kruger Park and in 2016, PFAS were found in the plasma of South African crocodiles from sites in the area, with PFOS the most frequent PFAS to be identified and occurring at the highest levels in the Flag Boshielo Dam.

In 2015, researchers also found the presence of PFOA and PFOS in African penguin eggs from Robben Island (Western Cape) and Bird Island (Eastern Cape).

In 2017, a study of adult male dragonflies at six sites (Tzaneen Dam and Soekmekaar Dam in Limpopo, Vlakfontein Dam in Mpumalanga, Potchefstroom Dam and Bloemhof Dam in North West and Bronkhorstspruit Dam in Gauteng) found that PFOS was detected in all individuals studied, with the highest levels in the southern sites close to industrial areas, particularly in the Bloemhof Dam.

This study suggests that because “per-fluorinated substances are not known to be manufactured in South Africa”, the residues in the dragonflies “are likely to have been derived from imported products”.

The result: reduced hatching success of dragonfly eggs, slower larvae development, increased larval mortality and impaired metamorphosis. If there is PFOS in the dragonflies, whatever eats the dragonflies (fish, birds) will be exposed to PFOS too.

In 2018, a study on the presence of PFAS in fish, invertebrates, sediment and water in the Vaal River found that “a potential risk for humans through consumption of PFAS-contaminated fish was assessed.

Tolerable daily intake values (grams of fish that could be eaten daily without risking health effects) were much lower than the average South African fish consumption per day, implying a potential risk for human health through consumption of PFAS-contaminated fish” (my emphasis).

Per-and Polyfluroalkyl substances (PFAS) were found in the African Marigold, commonly used for the treatment of diabetes. (Photo: gardenia.nt / Wikipedia)

In 2019, research found that PFOA, PFOS and other PFAS found in the Salt River were likely to accumulate in the African Marigold (Tagetes erecta) — a medicinal plant that is commonly used in diabetes management, suggesting that these plants — and others — are at risk of contamination and could also be a conduit of PFAS into humans. The study also found that the concentration of PFOA was much higher than in other rivers globally.

In 2020, PFAS were found in the aMatikulu and uMvoti estuaries in KZN. The study found that “PFOA concentrations in the uMvoti water samples were the highest recorded to date in South African waters” (my emphasis), and that “PFOS concentrations in fish tissue samples were significantly higher than other PFAS” but were below the calculated minimum risk levels for safe human consumption.

Also in 2020, PFAS, particularly PFOS and PFOA, were found in samples from Daspoort, Zeekoegat and Phola wastewater treatment plants in Gauteng.

The study explained that most PFAS are released to wastewater treatment plants during manufacturing, commercial and industrial uses, but that wastewater treatment plants are not optimised for the removal of PFAS. PFOA was found in the Daspoort sample only, while PFOS was found in all three.

Five other PFAS were found too. The findings include that water from these wastewater treatment plants would be “discharged into the environment, and even though there will be some dilution, the concentrations could still be harmful to users as well as the flora and fauna communities in the receiving water bodies” (my emphasis). Daspoort services the central business district of Tshwane, where many of our government officials live and work.

At least four PFAS per sample were found in 23 dairy milks and nine infant formulas from South Africa in 2020.

The study found that “although the EDI (estimated daily intake) of PFAS through the consumption of infant formulas and dairy milk are lower than the daily tolerable limits, the relative importance of long-term exposure and the cumulative effects of multiple exposure pathways cannot be overemphasised” (my emphasis).

For those of you wondering, the levels were highest in full cream milk.

The researchers also suggested that the levels of PFAS were likely to be influenced by the collection, preparation, manufacturing and packaging processes, and not necessarily the composition of the milk itself, though this needs to be researched further.

Then there is the first study that I mentioned in this series — the 2021 one on the presence of PFOS in Hartbeespoort Dam, which noted that “high PFAS concentrations were detected in water samples that passed through highly populated, industrial and agricultural areas, and the inflows with the highest contribution to the dams showed the highest levels of PFAS as well”.

The report concluded that the high concentrations of PFOA and PFOS could be due to the industrial and domestic activities around the dam’s catchment, and that since “PFAS are not produced in South Africa… the presence of these chemicals in the environment is probably from imported PFAS-containing products”.

The sampling point with the highest concentrations of PFAS was point C — the Crocodile River inflow — which represents about 90% of annual inflow into the dam and drains a highly industrial and urbanised area. One of the tributaries of the Crocodile River is the Jukskei River, which has a history of pollution and waste-dumping along its banks and is currently polluted by sewage.

“The source could be from PFAS-containing products which are either disposed of or flushed down the sewer. They could also come from other sources such as the use of fluorochemicals in manufacturing consumer products,” says Prof Jonathan Okonkwo, Rand Water research chair in organic chemistry at Tshwane University of Technology and an author of the Hartbeespoort study.

“PFAS are added into products because of their unique properties, such as water repellent. They can leach out of materials into the environment over a period of time.”

How long they’ve been leaching is hard to tell, but Okonkwo’s study points to high levels present in the water now, possibly putting the people who live in the area and use the dam at risk.

“A study needs to be conducted to verify any common ill health among the inhabitants of the areas with symptoms associated with PFAS. However, increasing use of water from these sources will increase exposure risks to PFAS,” says Okonkwo.

But for us to flush products containing PFAS down the toilet, or chuck them into a river, we have to have them first. And it seems that since PFAS are in every province, we are all using them — or are exposed to them.

All of the studies referenced above suggested that PFAS were not being manufactured in South Africa and thus must have been imported.

However, one 2020 report in the journal Science of the Total Environment did mention a potential local source. The report, which summarised the presence of PFAS in Africa, noted:

“There are several fluorochemical industries in South Africa, such as Pelchem, a manufacturer of fluoropolymers and perfluorocarbon liquids from fluorspar. However, since these industries have not reported manufacture of PFAS, it is not clear if such industries could be point sources of PFAS.”

And where is Pelchem, you might ask? Just upstream from the Hartbeespoort Dam, alongside the Crocodile River.

Find out more in Part Three of this series. DM

What is the eventual product of the flourine that is added to our drinking water? Could this be part of the problem?

Unfortunately, now that we have very sensitive analytical methods, we can find toxic chemicals almost everywhere (although usually in very small concentrations that do not present immediate health or environmental challenges). As this article suggests, the real challenge is to identify the compounds that are potentially problematic, determine where they come from and then take action to reduce them. This is a global problem and there are global efforts to identify such compounds and restrict their use. The most success was the identification of chlorofluorocarbons used for refrigerators and air conditioners and the subsequent banning of their use because of the environmental damage they were doing.