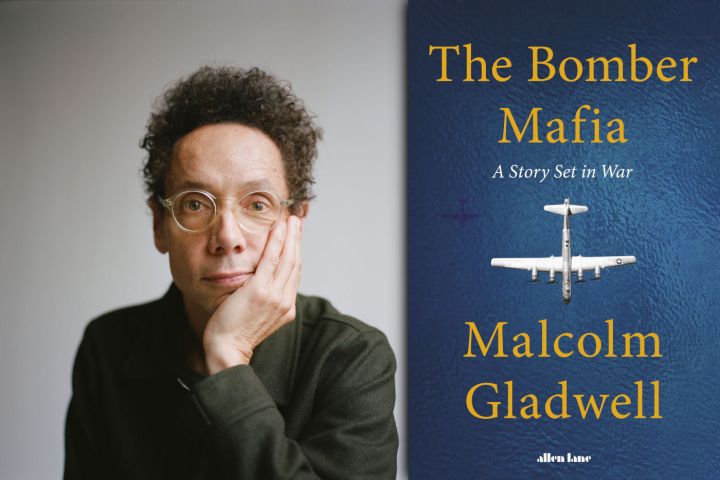

REVIEW

A book in service to Malcolm Gladwell’s war obsession

In The Bomber Mafia, author Malcolm Gladwell retells the events of the 1945 bombing of 67 Japanese cities by American forces, while taking a closer look at the technological innovation and ideological contestation at the heart of one of the most significant acts of war in modern times.

“This is a story I’ve been wanting to tell… the kind of story I’ve been wanting to tell for a very long time,” author and New Yorker staff writer Malcolm Gladwell tells Maverick Life during a Zoom call to discuss his latest book, The Bomber Mafia, published in April 2021.

Unlike some of his other popular titles, such as The Tipping Point and Outliers, The Bomber Mafia is not necessarily a deep dive into some area of popular social psychology, nor does it offer up the kinds of questions and answers that readers might find easily applicable in understanding the events in their own lives or communities. In fact, even the way it came about is unusual for Gladwell, starting off as material from his podcast, Revisionist History, then later expanded into an audiobook, and finally committed to print, as a book.

As per its title, it follows the actions of the “Bomber Mafia”, the unofficial name given to a small group of American military officers who advocated for the role of precision-bomber aircraft in war, and particularly those who believed in the potential of precision bombing as a more “humane” way to win wars, rather than indiscriminately bombing areas, resulting in large-scale civilian deaths. Specifically, Gladwell narrates the events leading up to the March 1945 napalm firebombing of 67 Japanese cities by the US, killing a reported 100,000 Japanese people in a matter of six hours.

In his author’s note, at the beginning of the book, he writes: “This book was written in service to my obsessions… I realise, when I look at the things I’ve written about or explored over the years, that I’m drawn again and again to obsessives. I like them. I like the idea that someone could push away all the concerns and details that make up everyday life and just zero in on one thing – the thing that fits the contours of his or her imagination. Obsessives lead us astray sometimes. Can’t see the bigger picture. Serve not just the world’s but also their own narrow interests. But I don’t think we get progress or innovation or joy or beauty without obsessives.”

Stories of war and military aviation are something of an obsession for Gladwell. As he explains, “you can’t see it [on this Zoom call], but I have rows and rows of books, and have had for years, on bombing and on airplanes”.

“There is something that has always puzzled me about technological revolutions. Some new idea or innovation comes along, and it is obvious to all that it will upend our world.”

In his telling of this part of World War 2 history, two characters take on central roles. There’s Haywood S Hansell Jr, who was made commander of the XXI Bomber Command in 1944. Being a member of the Bomber Mafia and a fierce proponent of precision attacks, he was tasked with using these precision tactics to destroy Japan’s military capabilities, making way for a land invasion. However, due to numerous difficulties outlined in detail in the book, including climate conditions and the then-nascent technology’s drawbacks, the attacks were unsuccessful. He would eventually be replaced by the book’s other central character, Curtis LeMay, in January 1945. Convinced that Hansell and co’s high-altitude precision bombing was ineffective, LeMay would go on to command the abovementioned low-altitude area bombing that would kill 100,000 Japanese people.

The men’s different approaches, and Gladwell’s take on them, informs much of the book’s tension, be it between the characters, the old and the new, or the positive potential of technological innovation versus its potential to be used for destructive ends. Indeed, the question of what ends technological innovation might lead us to is one that Gladwell brings up early on in the book.

He writes: “There is something that has always puzzled me about technological revolutions. Some new idea or innovation comes along, and it is obvious to all that it will upend our world. The internet. Social media. In previous generations, it was the telephone and the automobile. There’s an expectation that because of this new invention, things will get better, more efficient, safer, richer, faster.

“Which they do, in some respects. But then things also, invariably, go sideways. At one moment, social media is being hailed as something that will allow ordinary citizens to upend tyranny. And then in the next moment, social media is feared as the platform that will allow citizens to tyrannize one another. The automobile was supposed to bring freedom and mobility, which it did for a while. But then millions of people found themselves living miles from their workplaces, trapped in endless traffic jams on epic commutes. How is it that, sometimes, for any number of unexpected and random reasons, technology slips away from its intended path?”

However, it is clear in the book that he considers the ideas developed by Hansell and the Bomber Mafia as key innovations that have led the world to warring with far fewer casualties than before. “In the Second World War, we tried and failed at putting the idea of precision bombing into practice. The technology wasn’t ready yet. And so we ended up with great moral consequences… but [Hansell] put us on the path that we’re on today, which is… today we don’t destroy entire cities, or at least not on the [scale] we did in the Second World War.

“If we’d fought the war in Iraq in the way we fought in the Second World War, there would literally be no buildings left standing, civilian casualties would have been 10 times what they were; they were pretty terrible, but they would have been far worse if we were using the techniques of the Second World War. I think what Hansell was doing was saying that military leaders have a responsibility to redirect their energies to find more humane ways of fighting.”

That is not to say that the book strictly portrays LeMay as a bloodthirsty villain. At one point, Gladwell seems to argue that the swift firebombing campaign that killed tens of thousands of civilians, led to a quicker end to the war. “Curtis LeMay’s approach brought everyone – Americans and Japanese – back to peace and prosperity as quickly as possible,” Gladwell writes. And in the relatively short book’s closing sentence, he concludes: “Curtis LeMay won the battle. Haywood Hansell won the war.”

Elaborating on that sentence, Gladwell explains that the Bomber Mafia’s idea was that the future of warfare lay with precision as a way to solve one of the central problems that plagued war for generations, which was that in order to defeat your enemy, you had to kill hundreds of thousands of your enemies, including innocent civilians, and you had to destroy entire cities or level entire civilisations. “And I think that is an admirable legacy… we can thank Hansell and the rest of the Bomber Mafia for urging us to go down that road.”

That said, some have questioned Gladwell’s take of the story, including some of his conclusions and omissions. In his mostly positive review for The New York Times, Thomas E Ricks writes: “I enjoyed this short book thoroughly, and would have been happy if it had been twice as long. But when Gladwell leaps to provide superlative assessments, or draws broad lessons of history from isolated incidents, he makes me wary. Those large conclusions seemed unsubstantiated to me.”

“Technological advances do not resolve the broader strategic problems associated with waging war. They don’t make our leaders smarter. They don’t make the decisions we make wiser. They don’t make the choices we face easier.”

In an article for The Washington Post, author and historian Diana Preston observes: “Gladwell does not explore how racial attitudes influenced the bombing of Japan. Hansell noted ‘a universal feeling’ among US forces that the Japanese were ‘subhuman’. Adm William Halsey described the Japanese as ‘yellow monkeys’. LeMay himself – a future running mate, as Gladwell notes, of segregationist presidential candidate George Wallace – recalled: ‘Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at the time… I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal.’”

In response, Gladwell says he wanted to focus the book on the moral dilemmas faced by the two men he chose as central characters, as well as put forward questions about technology and the “necessary messiness” with which it enters the world.

“And once you have those choices in mind, it disciplines your story. The problem with the Second World War is that you can go on forever.” And specifically to Preston’s observation about the book’s omission of the story of racist American attitudes towards the Japanese, he says “that was a deliberate choice, as I felt that’s a different book. Someday, I might write that book. Others have already written that book. It’s a crucial part of the story… I worried if I did a chapter on that aspect; first of all, it wouldn’t do justice to what is an incredibly important topic. But secondly, it wouldn’t fit, and as storytellers we have to understand that you can’t consider every element in one narrative, you have to choose your approach.”

While the book seems to urge readers to take a positive look at the consequences of both the moral convictions and the technological innovations that would eventually make precision warfare possible, Gladwell maintains some reservations about the repercussions of said innovations. He wonders if, as a consequence, the technology has not made it easier for governments to go to war, knowing that they need not worry about the bad “PR” that would have come with large-scale civilian deaths.

“Technological advances do not resolve the broader strategic problems associated with waging war. They don’t make our leaders smarter. They don’t make the decisions we make wiser. They don’t make the choices we face easier. In fact, in some ways, they complicate matters, because the political barriers to go into war now are very low. If you’re the president of the United States, you could be waging war using drones and precision weapons on a continuous basis. You could argue that during the Obama administration the war never stopped,” he observes.

As for the Bush administration’s decision to go to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, he calls it “one of the most morally reprehensible decisions of the last 50 years. It served no strategic function and resulted in the devastation of countries for no good reason.” And he asks, “was that decision to go to war made easier by the fact that we can wage wars in a way that is much more surgical and precise? I think it probably was. Let’s not delude ourselves into thinking that technology can ever solve broader moral and strategic problems. It cannot. In many ways, it makes them harder.”

And if there is a cautionary note to be found in this exploration of Gladwell’s obsession with 20th-century wars and their technology, it is, as he says, that the “introduction of technology is never as clean and predictable as we would hope”.

Contemplating the future of war, and which technology that is currently being developed might shape it, he points to gene-editing technology such as CRISPR.

Says Gladwell: “The possibility for biological warfare in the future will be enabled on the back of CRISPR gene-editing techniques, which have enormous potential for curing diseases, but also have potential for creating viruses that can destroy a huge swath of humanity. I mean, did the people who invented CRISPR think through all of those? They were very focused on the good it could do; and I think, in retrospect, they paid too little attention to the potential for harm. So I think the Bomber Mafia were similarly mistaken in their understanding of technology; they [did] the thing that technological innovators often do. They assume that because they can very clearly see the consequences of a particular technology, that the rest of the world will be as eager and as rational as they are. And that’s just not true.” DM/ML

Yes, die hard supporters of Gladwell who read him for his take on social psychology issues, will be disappointed. On the other hand, those like me who read both Gladwell’s fare as well Military Aviation History subjects, hit the jackpot with this one! It covers both.

On the Military History side, he put something completely new on the table: The Bomber Mafia. Not even Curtis Lemay was part of this gang, or even aware of their existence…and as far as strategic air war goes, Curtis Lemay is The Man. So that says a lot about Gladwell the sleuth who dug up this little pearl. (FYI: Curtis Lemay is not the kinda guy that you can cover in a “little book” like this…all of the pages in The Bomber Mafia would just about cover the introduction in LeMay’s bio.)

On the social psycho side, the nuggets are there, just not as well polished as usual. This time around, they’re not the main players. But if you wonder what happens to society when it’s getting bombed back to the stone age…it’s all in there. (The short answer is: life, and it’s little squabbles, goes on.)

Or why would a deeply religious man like Norden develop a bombsight? (He believed that as war is inevitable, his calling was to minimize the killing of innocents through accuracy.)

Or that we store some of our memory in others. (That’s why when we lose a partner, we feel like we’ve lost part of ourselves. We have.)

Or what happens when true believers’ believes don’t come true? Read the book…it’s all in there!

A very interesting read, thank you. In doing research for a paper I am writing on the history of the antifriction bearing industry I came across a memoir by Brigadier Hansell wherein he describes the identification of strategic targets for bombing raids on Japan, the selection was made by a Committee of Operations Analysts. For some odd reason they decided that factories producing bearings and electronic products were not of any importance. Contrast this with the relentless bombing raids by the allies in the European theatre targeting bearing factories in Schweinfurt and Canstatt and by the Luftwaffe on similar targets in the UK.

“In those days, we anxiously asked ourselves how soon the enemy would realize that he could paralyze the production of thousands of armaments plants merely by destroying five or six relatively small targets.”

– Albert Speer, the German Minister of Armaments Production during WWII referring to the prospect that the bearing factories would be targeted.

I suspect that in the selection of targets for bombing raids there was an element of, shall we say, consideration for technical advances that would have implications for trade long after the hostilities had ceased.