FROM OUR ARCHIVES

Hiroshima 70 years on: Was the Armageddon worth it?

With the 70th anniversaries of the atomic blasts over Hiroshima and Nagasaki coming up shortly, J BROOKS SPECTOR looks at the backstory of the two weapons that ushered in the nuclear age – and helped bring World War II to a conclusion.

Some 30 years ago, the author was living and working in northern Japan. One evening, a casual conversation with a Japanese colleague turned to the events of World War II. Up to 1945, our Japanese friend had been a young teenager, but still too young to be drafted into the actual Japanese military. Nonetheless, as we sat in a convivial pub over a mug of Sapporo Draft beer or two, our friend leaned forward to explain that in the spring of 1945, just as the war was heading into its final months, despite his youth, he had finally been hauled into militia training for an expected last-ditch, suicidal fight to the death, once the Allies launched their seemingly inevitable attacks on the four main Japanese home islands – Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and Hokkaido.

And what did his training consist of? He was taught to pop up out of a foxhole and instructed in how to shove the business end of a long bamboo pole, with a packet of high explosives attached, under the treads of any oncoming Sherman tank. He knew that if he had had actually been ordered to carry out that task, he would not have survived the ordeal; but, like an obedient soldier-to-be of the emperor, he practiced this manoeuvre until he could do it quickly and silently.

Fortunately for our friend, it never came to that. There was, in fact, no all-out invasion of the home islands and he never had to carry out the suicide mission. Instead, after the beach landings and the bloody fighting that culminated in the conquest of Okinawa, a smaller island south of Kyushu, there was a hiatus in ground battles while the Americans gathered their forces for the massive, anticipated invasion, code named Operation Downfall; an operation designed to bring the Pacific War to a close. And then, suddenly, the two atomic bombs were detonated over Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9 1945 (although the Japanese mark their commemorative observances a day later than in the West, due to the International Date Line).

Less than a week after that second explosion, the Japanese emperor finally recorded a surrender message that was broadcast to the entire nation for the Japanese “to endure the unendurable”; an unconditional surrender to the many forces now arrayed against them, and augmented, finally, by the Soviet Union’s forces moving quickly into Manchuria, after that country entered the war on August 8. And the bitter fighting that had raged all across East and Southeast Asia and the vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean finally drew to a close.

Ever since the two specially outfitted B-29s – nicknamed the Enola Gay and Bock’s Car – had delivered their lethal cargos, the US military’s use of those two weapons and the terrible cataclysms they caused had ushered in the atomic age, controversy has continued to rage over their use again two largely civilian targets. And this controversy has never really ended.

In 1994, just prior to the 50th anniversary of the dawn of the nuclear age, the Smithsonian Institution decided to install the fully restored fuselage (but not the wings because of space reasons) of the Enola Gay in a specially prepared exhibition hall of the Air and Space Museum. Unsurprisingly to pretty much everybody except perhaps the museum officials, a furious debate about the bomb and the Smithsonian’s exhibition of Enola Gay quickly ensued, since the Smithsonian had also planned seminars and colloquies around the exhibition, covering the legacy of the bomb.

Veterans groups quickly mobilised in retaliation, taking serious public issue with the analysis contained in some of the papers prepared for those meetings, especially where authors argued that the use of the atomic bombs (and the death and destruction) had largely been unnecessary to force a Japanese surrender. Instead, for some, the deployment of the atomic weapon had largely been intended to serve as a warning to the Soviet Union, rather than as a means of drawing a terrible war to a decisive finish.

Not surprisingly, the veterans groups, and yet more scholars felt such analyses – and the way they were being presented – deeply demeaned the extent of the sacrifice of the many thousands of Allied servicemen who had died or were wounded in defeating the Japanese, or who had been prisoners of war of the Japanese in absolutely dreadful conditions. The Japanese Embassy and government, meanwhile, soon found themselves in the midst of the snarling verbal and print cat fight in Washington.

The Smithsonian officials responsible for the exhibition were effectively accused of trying to whitewash history by attempting to find a middle path in the midst of all this arguing in their choice of the captions and photographs that were also part of the Enola Gay installation. In the end, as a result of all this public wrangling, on the actual day of the anniversary of the dropping of the bomb, the museum chose to do nothing special to mark the event, other than have the plane on display. And the head of the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum, Martin Harwit, was compelled to resign in the wake of all of this unpleasantness.

But what of the actual bomb itself? Its origins go back at least as far as 1939, even before there was a real government project to undertake the research that became the Manhattan Project, that massive ultra-secret effort to create the first atomic weapons. Back in the summer of 1939, at the instigation of several other nuclear physicists, refugees from Nazi Germany, Albert Einstein, who was himself a refugee but also, crucially, the nation’s best-known theoretical physicist, was convinced to sign a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt, just as war was about to erupt yet again in Europe, warning that Germany could well develop the capability to produce a nuclear weapon.

Einstein’s letter had read in part: “This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable — though much less certain — that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. However, such bombs might very well prove to be too heavy for transportation by air … In view of this situation you may think it desirable to have some permanent contact maintained between the administration and the group of physicists working on chain reactions in America. One possible way of achieving this might be for you to entrust with this task a person who has your confidence and who could perhaps serve in an unofficial capacity.

“His task might comprise the following:

a) To approach government departments, keep them informed of the further development, and out forward recommendations for government action, giving particular attention to the problem of uranium ore for the United States;

b) To speed up the experimental work, which is at present being carried on within the limits of the budgets of university laboratories, by providing funds, if such funds be required, through his contacts with private persons who are willing to make a contribution for this cause, and perhaps also by obtaining the co-operation of industrial laboratories which have the necessary equipment.

“I understand that Germany has actually stopped the sale of uranium from the Czechoslovakian mines, which she has taken over. That she should have taken such early action might perhaps be understood on the ground that the son of the German Under-Secretary of State, Von Weishlicker (sic), is attached to the Kaiser Wilheim Institute in Berlin where some of the American work on uranium is now being repeated.” Uh-oh.

Once war did come to Europe and as the US finally entered it fully in 1941 after the Japanese seaborne aerial attack on Pearl Harbor, it became inevitable that an effort to produce a nuclear weapon, the Manhattan Project, would grow into a multibillion-dollar, secret programme that employed thousands of the country’s best scientists and technical staff. This vast enterprise eventually worked out both the mechanics and the physics of nuclear weaponry, produced the required fissile materials for one nuclear test device, and then – ultimately – manufactured the two bombs.

By July 16 1945, that first device was tested on the remote desert wastes near Alamogordo, New Mexico. At the moment of that fierce explosion, Dr Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who had guided the scientific work for the entire project, had famously recited words from the Bhagavad Gita as his personal grim foreboding of baleful things to come. He whispered to the others watching the test explosion with him: “I have become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The irony in this was that the German nuclear effort had ultimately come to naught. (A lack of commitment to fund and carry out all the necessary research, some poorly understood physics and inaccurate mathematical calculations were the proximate causes) And, in fact, Germany had surrendered several months before that first test of the nuclear device in the New Mexico desert, let alone before there was any feasible chance to employ the new weapon against Germany – the original target.

But there was still an increasingly barbarous fight against Japan to be waged – with military planners expecting around 200,000 casualties on the Allied side alone. As a result, with the changed circumstances of the war in Europe, military planners increasingly turned their attention to the possible use of the bomb against Japan to bring the Pacific war to a conclusive end, before having to launch the brutal invasion of those home islands. Looking at things from the Japanese side, historian Kazutoshi Hando, head of Japanese research group The Pacific War Research Society, had written in Japan’s Longest Day, some more despairing Japanese generals were increasingly worried that the Japanese army as a whole might well look forward to a final suicidal battle, despite the long odds of such a thing. (By the way, this thoroughly researched book was eventually made into a well-regarded Japanese film as well, starring Toshiro Mifune among others.)

As Hando had written of the country’s Eastern Military District commander, General Shizuichi Tanaka: “He understood the army point of view, of course, as did every officer trained in bushido: no retreat, no surrender, and an eagerness to die in defence of the homeland. Three million troops scattered across Japan had been imbued with the same belief: how strong a breath would it take to fan their smoldering ardour into flame? It was a flame that might well scorch the entire country. Seven thousand planes were available to suicide squadrons: if these were put to use, would the enemy be tempted to show quarter?”

With a fear of precisely this kind of resistance to a planned invasion, US military planners began drawing up a list of potential targets for a decisive aerial strike. Several cities were purposefully kept off the list for the mass bombing raids that became possible by the beginning of 1945 as bases were built on captured Pacific islands. These were the highly destructive firebombing raids carried out on the largely wood-built cities located all across Japan with munitions factories situated in the midst of residential areas.

To reserve a city marked it as a place where an atomic weapon might be employed, should such a weapon prove achievable. After one major bureaucratic battle, Secretary of War Henry Stimson had managed to keep Kyoto off that list of targets on the grounds that destroying the city would guarantee the kind of mass revulsion in Japan that could keep the war going, despite the increasingly dire odds for the Japanese. Moreover, as he successfully argued, once peace finally came, if Kyoto had been levelled, the Japanese would carry their hatred of Americans for generations for having vaporised their nation’s cultural heartland.

When the Okinawa campaign began on April 1 its primary objectives were the air bases that would be vital to the projected invasion of Japan. In a three-month campaign that ended on June 22 and destroyed much of the island’s infrastructure, Japan lost more than 77,000 soldiers while the Allies suffered more than 65,000 casualties — including some 14,000 fatalities. At that point, war planners, mindful of that fight-to-the-death spirit, began the task of contemplating the next move to force the Japanese to surrender.

Historian Gregg Herken, writing in The Washington Post the other day, described the uncertainties of any planned invasion of the main islands, noting: “In his post-war memoirs, former president Harry Truman recalled how military leaders had told him that a half-million Americans might be killed in an invasion of Japan. This figure has become canonical among those seeking to justify the bombing. But it is not supported by military estimates of the time. As Stanford historian Barton Bernstein has noted, the US Joint War Plans Committee predicted in mid-June 1945 that the invasion of Japan, set to begin November 1, would result in 193,000 US casualties, including 40,000 deaths. But, as Truman also observed after the war, if he had not used the atomic bomb when it was ready and GIs had died on the invasion beaches, he would have faced the righteous wrath of the American people.” In fact, no politician, no military commander could have withstood such anger, given the horrific casualties so recently experienced in Okinawa, had they also sent thousands more troops to land and die on Japanese beaches when another way was at hand.

But, once the decision to use the new weapon had been made, the question was whether it should actually be used on a city — or was there some other way to demonstrate its power and astonish the Japanese into surrender? Again, as Herken notes: “The decision to use nuclear weapons is usually presented as either/or: either drop the bomb or land on the beaches. But beyond simply continuing the conventional bombing and naval blockade of Japan, there were two other options recognised at the time.

“The first was a demonstration of the atomic bomb prior to or instead of its military use: exploding the bomb on an uninhabited island or in the desert, in front of invited observers from Japan and other countries; or using it to blow the top off Mount Fuji, outside Tokyo. The demonstration option was rejected for practical reasons. There were only two bombs available in August 1945, and the demonstration bomb might turn out to be a dud.

“The second alternative was accepting a conditional surrender by Japan. The United States knew from intercepted communications that the Japanese were most concerned that Emperor Hirohito not be treated as a war criminal. The ‘emperor clause’ was the final obstacle to Japan’s capitulation. (President Franklin Roosevelt had insisted upon unconditional surrender, and Harry Truman reiterated that demand after Roosevelt’s death in mid-April 1945.)

“Although the United States ultimately got Japan’s unconditional surrender, the emperor clause was, in effect, granted after the fact. ‘I have no desire whatever to debase (Hirohito) in the eyes of his own people,’ General Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of the Allied powers in Japan after the war, assured Tokyo’s diplomats following the surrender.”

Still, even that analysis would appear to be avoiding the fact that the Japanese emperor’s surrender announcement by radio – and thus the country’s actual surrender – almost didn’t happen. The emperor had made two recordings (he would not speak live on radio), but a violent mutiny within some elements of the army nearly captured and destroyed the recorded surrender message before one could be broadcast – and some generals were poised to take control of the country’s fate at that delicate moment.

It is true that even the atomic bomb – or rather, the two bombs – was, in fact, not enough to give the Japanese their final push into surrendering. The Japanese had been counting on the Soviet Union to assist them in moving towards a negotiated settlement with the US and the Allies, but the USSR’s declaration of war exactly three months after the German defeat – and its quick invasion of Manchuria and the Kuril Islands – just two days after the first bomb struck Hiroshima (in line with Joseph Stalin’s promise at Yalta to the western Allies) profoundly shook the Japanese – and the second bomb would appear to have been the final straw that pushed the decision-makers into throwing in their hand.

In thinking about the intention for the use of the bomb, revisionist historians have argued since the 1970s that a hidden but real purpose of the deployment of the atomic bomb (and thus a quick surrender) was to preclude the Russians playing any significant role in the post-war settlement with regard to Japan, once the Russians themselves were sufficiently awed by the awful power of that weapon. But the Russians were still, at least in American eyes, major allies who had, jointly, beaten the European fascist menace. The split would come, but not in the midst of the war itself. Instead, it was the military decision that was key. The decision was that the bombs be deployed “as soon as made ready”, largely due to casualty projections and fears of a drawn-out battle for Japan’s home islands.

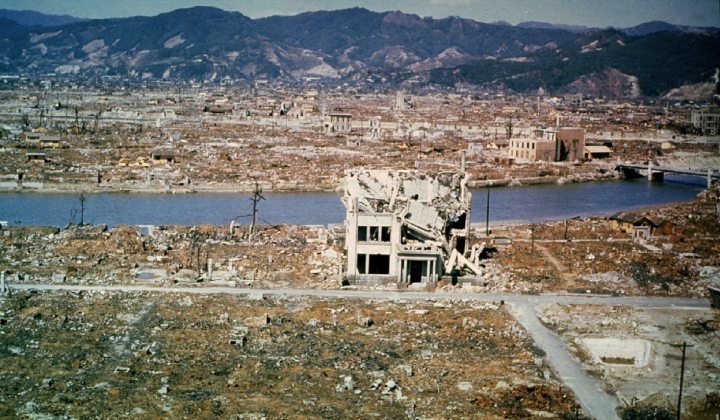

Of course the immense human tragedy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki loomed increasingly once the war was over and the real effects of those two weapons became better known. Crucial to that change was John Hersey’s extraordinary essay, some 30,000 words long, published in The New Yorker’s August 31 1946 issue, the story entitled simply, Hiroshima, and constituting the entire editorial content of the edition. Detailing the horrific human cost of the bomb, as well as its aftermath as an entire city was devastated, and people forced to forage for unobtainable food, water and medical care, Hersey brought home to his readers the enormous change in warfare – and in the future itself – that came to be, just a few minutes after 8am on August 6 1945.

Amazingly, despite the enormous devastation and horrific scenes of people with dreadful wounds and previously unknown health conditions, the Japanese began to dig out and rebuild their levelled city. Hiroshima actually managed to get its remaining streetcars up and running just three days after the bomb struck. Not surprisingly, the bombs induced such a “nuclear allergy” in the Japanese that no rational person there will contemplate adding nuclear weapons to the armaments of the Japan Self-Defense Force – and even the construction of nuclear reactors continues to generate deep disquiet among the vast majority of the Japanese people.

And, as a footnote, the very act of deploying those two bombs has bred such an aversion to nuclear war in the rest of the world that despite the vast build-up of nuclear arsenals by major and minor powers alike, a whole division of diplomacy has been devoted to decreasing the number of nuclear weapons, to establishing enforceable international nuclear non-proliferation regimes, and to blocking new nuclear powers such as Iran and North Korea. All of this is also a legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s devastation at the end of World War II.

In all this, Einstein can be called the godfather of the nuclear age, both for his letter to Roosevelt that gave the impetus to the Manhattan Project as well as from his famous equation E = mc2 that opened the door to an understanding of nuclear energy. But he is also famous for his warning: “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.” DM

Note: Due to an archive issue, the inset photos that appeared when this article was first published in 2015 are not available.

For more, read:

- Letter from Albert Einstein to FDR, 8/2/39 at the PBS;

- Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at History.com;

- Hiroshima, the John Hersey essay, first published in the New Yorker then issued as a separate book;

- Five myths about the atomic bomb at the Washington Post;

- This 390-year-old bonsai tree survived an atomic bomb, and no one knew until 2001 (the astonishing story of a bonsai tree given to the US by a Hiroshima resident in 1976) at the Washington Post;

- Japan’s Longest Day, reviewed at Amazon.com;

- The tram that survived the Hiroshima bomb at the BBC; and

- Japan’s atomic bomb survivors continue in fight against nuclear weapons. As Japan prepares to mark the 70th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear attack, survivors ponder how to continue warning of the horrors of nuclear war at the Guardian.