Maverick Life

Miners Shot Down: The film every South African should see, and never forget

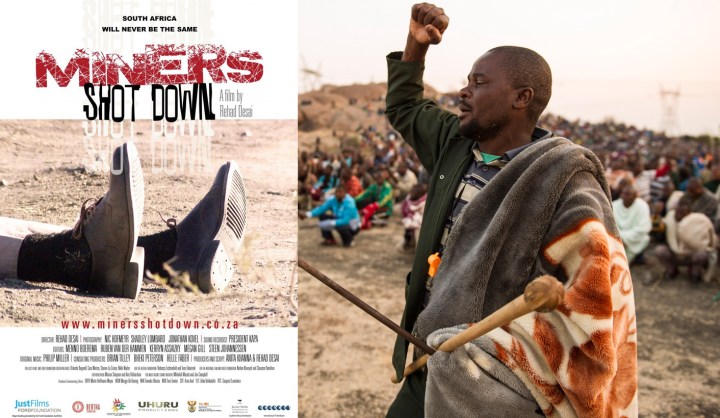

Rehad Desai’s beautifully filmed and uncompromising documentary, ‘Miners Shot Down’, is about so much more than the massacre by police of 34 striking workers at the Lonmin platinum mine at Marikana in August 2012. The film offers a unique prism through which to view contemporary power relations in ‘democratic’ South Africa (and perhaps globally) where the unholy trinity of capital, politics and security were (and are) pitted against labour - poorly-paid, badly educated and exploited workers. The film also shows that the miners had been so shockingly “othered” that killing them was not beyond the imagination or capacity of those in power and authority. The movie just won the International Emmy Award for best documentary on Monday night in New York. By MARIANNE THAMM.

There is much that is disturbing and shameful in Rehad Desai’s tender 86-minute filmic exploration of events over six days in August 2012 leading up to what has become known globally as the Marikana massacre, one of the most disgraceful events to have taken place in post-Apartheid, “free” and democratic South Africa.

So significant were the tensions that played themselves out on the ochre koppies of Marikana that winter that they feature in the opening lines of the first chapter of Thomas Piketty’s book de jour, the international bestseller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

After describing the massacre, Piketty writes “this episode reminds us, if we need reminding, that the question of what share of output should go to wages and what share to profits – in other words, how should the income from production be divided between labour and capital? – has always been at the heart of distributional conflict.”

So, on one level what happened at Marikana was not just a tragedy for South Africa, but emblematic of the potential for state-sanctioned violence in the face of increasing inequality and impoverishment triggered by the 2008 collapse of global financial markets.

With Miners Shot Down, Desai has crafted an intimate, claustrophobic and deeply moving film using footage taken at the scene over the course of the strike and interwoven with SAPS and Lonmin security videos. The narrative trajectory is driven by interviews with key players in the saga, including union and strike leaders, politicians and legal representatives of families at the Farlam Commission of Inquiry.

Watch: Miners Shot Down

The director’s own voiceover from the start uncompromisingly establishes and situates his sympathies with the workers, their struggles, their working conditions and their role, as young black men, in the continuing unhappy history of the mining industry in South Africa. Philip Miller’s haunting score threads throughout the film, lending it a fitting funereal gravitas.

What is disturbingly evident from the start of Desai’s film is the view of the striking workers as being somehow outside of the “system” or the “normal” or usual “channels” of control and coercion, i.e. NUM and Lonmin management.

It is clear that in refusing to allow NUM to negotiate on their behalf, joining the rival union AMCU or opting to attempt to bargain with Lonmin management themselves, the striking miners of Marikana changed the rules of the game – perhaps forever.

Desai sets this up the general viewpoint of the striking workers as “other” or “outsiders” using footage filmed by Lonmin’s security guards early into the strike as disgruntled rock drill operators initially gather at the mining house’s headquarters. The banal running commentary about what the camera is witnessing sets up the “us and them” narrative that begins to take shape around the issue of the R12,500 wage demand.

A second ludicrous encounter occurs when police send in a “hostage negotiator” to talk to the miners who have now gathered at the infamous koppie. A police armoured vehicle, its engine straining, drives up to the crowd. The police, and the Afrikaans-speaking negotiator, simply refuse to get out of the vehicle and talk to the miners face-to-face, human-to-human.

Instead they order the unarmed spokesmen for the miners to approach their vehicle and force one of them to stand on tiptoes on the grille in order to try and negotiate over the loud diesel rattle of the SAPS vehicle.

The third encounter where the “us/them” divide once again becomes evident is when provincial police commissioner, Major-General William Mpembe, confronts a group of miners, armed with spears and sticks, as they attempt to walk home through the veld. Mpembe explains that he is not going to arrest the strikers but has been ordered disarm them. One of the miners stands up and respectfully tells Mpembe that they have no quarrel with the police, that they will not cause trouble, but that they will not surrender their weapons.

The speaker then verbalises what so far has remained unsaid.

“You are black like us,” says the miner, casting his eyes over the jumpy police officers gathered around the Major-General while the workers softly begin to sing “basiyazi we we, basiyazi thina” (they know us).

For a brief moment it appears as if Mpembe and the older striking miner with whom he is negotiating are making headway – both men speaking respectfully to each other using the term “elder”. Then the Major-General’s phone rings, he takes the call and returns with an entirely different and much more confrontational mindset.

And it is as this group of cowering workers rise up to begin walking home through the parched veld against police orders that the tragic events that will end in shortly in 34 deaths and at least 70 injuries are set in motion, Desai sweeping the viewer along in each horrific moment.

In the most shocking display of apparent dissociation, Desai shows how after that awful crack of lethal live ammunition that has been fired at the fleeing strikers – police callously move among the dead and the dying, overturning bloody bodies, putting a boot firmly on a chest to search for a weapon, simply ignoring the death rattle of a wounded man or the panicked gaze of another.

These are scenes disturbingly reminiscent of documentary filmmaker Lindy Wilson’s Gugulethu Seven, about seven ANC operatives who were lured to Gugulethu and assassinated by Apartheid police in 1986. At the TRC, footage was shown of police manhandling the bodies of the dead men in a similar fashion. Desai knows that those South Africans who survived the violence of Apartheid will make those visual connections and be horrified and outraged.

In this regard, Miners Shot Down follows in a great tradition of films that helped to change the course of South African history over the last 50 years. Documentaries such as Chris Curling and Pascoe Macfarlane’s influential 1974 Last Grave at Dimbaza, which helped to galvinise global opinion against the Apartheid government as well as many others such as Betty Wolpert’s 1981 Awake from Mourning and Wilson’s other acclaimed 1983 documentary, Last Supper at Horstley Street, about District Six forced removals.

From this perspective it is only fitting, then, that the current regime would not – as was the case with their political predecessors – be too keen for ordinary citizens to see this important and courageous film, which is why it will not be screened by the SABC.

It is enlightening to watch ANC Deputy President, Cyril Ramaphosa, whom Desai has beautifully captured in both pre- and post- democracy incarnations. The juxtaposition of the young, thin, bearded firebrand who established NUM and the fat, shiny, bemused tycoon speaks entirely for itself.

The absences in the film – the list of those who refused to be interviewed – including President Jacob Zuma, former Police Minister, Nathi Mthetwa, Police Commissioner Riah Phiyega, NUM Secretary General Frans Baleni or anyone from the Lonmin executive – also speak volumes.

Desai’s ability to reconnect the dead miners – those working men whom the mines so often view as disposable or replaceable (as the workers themselves tell the camera) brings to the film a human solidarity that is so lacking in the response from politicians, officials, the SAPS and Lonmin executives.

It is worth asking why the Marikana massacre and what is represents played such a minor role in this year’s general election. Juluis Malema’s EFF was the only party that understood the greater significance of the underlying currents that led to the massacre in August 2012, and that bothered to address the underlying issues that are not going to go away soon.

That the majority of South Africans did not take to the street in outrage is testimony the effectiveness of the state media and the ruling party’s ability to dazzle voters with singing, dancing, rhetoric and big promises.

Miners Shot Down reveals exactly the nexus of power in this country, and no amount of officialese or political jargon can disguise it.

Rehad Desai is an accomplished filmmaker, and in time, Miners Shot Down will come to be seen as one of the most important physical remembrances, not only of the lives of the men who were killed, but also of a shameful and cowardly chapter of our recent history. It will show that liberation credentials mean nothing if true and meaningful transformation does not take place.

Ster-Kinekor is to be commended for showing this film on circuit across the country. You have a few days left to see it. Do so. DM

Photo: L) Poster for the movie, R) Lonmin employees gather on Wonderkop at Marikana, August 15, 2012, a day before the massacre. (Greg Marinovich)