Maverick Life

Gone but not forgotten: A love letter to Brenda

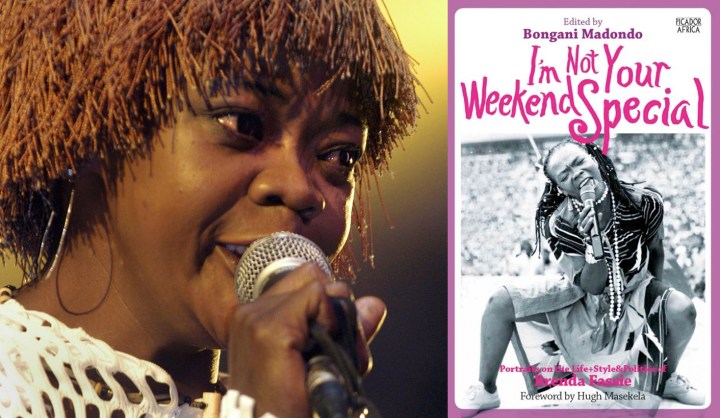

Brenda Fassie still has us in her thrall but we will never know her. Ten years after her untimely death in 2004, the Queen of African Pop, widely considered the most controversial diva of all, continues to perplex and evade her fans. It is fitting that Bongani Madondo, the editor of ‘I’m not your Weekend Special’, bills this collection of essays as “a love letter to Brenda”. The collection seeks to remember and to record her presence, as she cannot be defined. By MAUREEN ISAACSON.

Listening to MaBrrr’s music is always stirring; it is here that we will find all we need to know, if not all we want to know. Although it’s unlikely we’ll come closer to understanding the simultaneous urge to creativity and the destruction that devastated the woman Time Magazine dubbed the Madonna of the Townships, this collection provides insights.

Hugh Masekela, in his foreword, describes his own evolving responses to Fassie. First meeting her in Zimbabwe in April 1982, after she had already recorded her hit, ‘Weekend Special’, Masekela was impressed by her attitude; which he perceived as morose, arrogant and dismissive. He wondered, “How the hell would she make it in the entertainment world with such a fucked-up disposition?” A year later in Gaborone, Botswana, where she went to perform with her band, the Big Dudes, Masekela recalls her mesmerizing the Oasis Hotel’s sold-out poolside audience. She reminded him of Judy Garland and Aretha Franklin, “when they came hurtling onto the entertainment scene”. Also, MaBrrr was damned funny; she could laugh at herself. He writes, “I developed a sincere love for her artistic prowess and a deep respect for her compositional genius, virtuosity, simplicity, her smooth dancing and friendliness towards all. She had a warmth full of pomp.” She was also a super-arranger. Right up there with the greats, at Sally Mugabe’s 1988 UNICEF festival in Harare, Harry Belafonte invited her to join him during his performance. In the end, for Masekela, Fassie was sweet, often confrontational and usually joyful and vibrant amid a life of “spectacular tragedies, marriages, romances, breakups, sensational paparazzi truths and bullshit gossip.”

It was of course the “bullshit gossip” that hooked newspaper readers, and Fassie’s flamboyant sexuality took precedence in reports. Journalists were dying to let the world know that when she had invited them backstage, offstage and into her often, startling private life, she had flirted with them too.

These essays about Fassie recount different angles of her story, bring us closer to the Fassie experience; the rags to riches, the fancy houses, the presidential suites, all enabled by her magnetic brilliance, vaunting ambition; the elaborate wedding to Nhalanhla Mbambo in three stages, the Cadillac, the helicopter, the designer dresses and in Janet Smith’s report, the thirty thousand who turned up for the third leg of the wedding at the Princess Magogo Stadium in KwaMashu, when Bongani, Fassie’s son, was four years old. Among them were many poor souls who gulled by conmen to pay R10 upon entry to the event billed as free.

The Fassie experience brought forth a divorce, two years later, with reports of physical abuse. It brought the consequences of substance abuse: the dead lesbian lover, Poppy Sihlala, the raging battles of passion, the shards of broken lives and hearts and the scrabble for money after it all ended, and before that, visitors such as Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki at her bedside.

Brenda Nokuzola Fassie was born in the Western Cape township of Langa on 3 November 1964, the youngest of nine children. Her brother, Themba K Fassie, recalls the impact of Fassie’s arrival as the ‘last born’ in the family of the Fassies of the Madiba and Dlomo clans. Legend has it she hummed at birth. Dad, Mangaliso Stokie, who died when Fassie was two, worked at Barclays Bank; he was a disciplinarian, a sports fan and a very talented singer. Mother, Koko, was no match for him in this regard, but she was the lead pianist in a five-piece ensemble and she assembled a successful group called the Tiny Tots, when MaBrrr was four years old. The performance by the Tots for a bunch of European tourists docked in Cape Town was the beginning of Fassie’s amazing journey. Koloi Lebona, the big name producer, took Fassie from Langa to Soweto, aged 16, where he and his wife were to take her under their wing and ensure that she continued her education. Mpho Lebona, Koloi’s daughter, a baby in 1980 when Fassie came to live at their home, 1398 B Mavi Street, White City, Soweto, remembers her sadness when Fassie, who shared the sleeping couch with her and called her ‘Pom- Pom’, left their house. Mpho saw her as a big sister and later, she challenged her parents about their failure to rein Fassie in. She got in with the wrong crowd; dagga, cigarettes and alcohol proving too much for Mpho’s mother, Ethel, who called Fassie’s biological mother for help; received none and who remains haunted by the impossibility of her project. A teacher, from Pesesco High School (Phefeni) High, Soweto, a family friend, was asked to keep an eye on Brenda and reported that she was a brilliant performer, academically. But she bailed out and instead went to sing with Joy, the local vocal trio, famous for Paradise Road, later founding her own group, Brenda and the Big Dudes. ‘Weekend Special’ took her across the globe.

Andrew Herold recalls that it was when Fassie split from the Big Dudes – and her then husband, Dumisani Ngubeni, [Bongani’s dad], that she started recording with producer Sella “Chicco” Twala, on the 1989 album, Too Late for Mama. “Departing from the disco feel of her early tracks, the album was much truer to township music Mbaqanga – but with added drum machines and slick production. This Mbaganga-pop hybrid, known as Bubblegum, was a style Chicco was famed for, and one that Fassie’s impressive range and childlike intonations lent themselves to.”

Duma Ndlovu locates Fassie in the 80s during which time she came of age, with her song, ‘Black President’: “The year 1963/ The people’s president was taken away by security men/ All dressed in a uniform of brutality/ Of brutality/ Oh no!/ My Black president”. The song was immediately banned. Brenda and Chicco Twala paired up and sang not for but with the masses; Fassie bolstered Winnie Mandela, lending her voice to the collective, pent up energies of the struggle. Her song, ‘Good Black Woman’, was deep protest: “Early Monday morning/ Police arrested my brother/ For working for the black community/ Monday afternoon went to see my brother/ Police treated me like a donkey/ Oh no I am not criminal/ I am a good black woman!”

Ndlovu counters accusations that Fassie adopted a politics of convenience; she had judged the mood of the country and knew that she was too big to be arrested by the police, for her music. She was, in his view, the country’s much-needed voice, a channel for the pent-up energies and sorrows of black people. There were several dimensions. Fassie’s one-time lover of seven years, Ludwe Maki, in his ‘open letter’ to Fassie, remembers: “You had a remarkable manner of combining domesticity with your quest for singularity, for individuality and freedom as a woman, even at home.” He tells Fassie in this letter that she was a selfless person, who “gave, gave until you had nothing to give but yourself.”

Charl Blignaut recounts how as “a 22 year-old white moffie”, he got to interview Fassie in bed, and learned some details of the now well-known biography; her departure from Cape Town, and her move into the big time, her battle with the media, the indelible image which survived in spite of being haunted by Sunday times journalist Jani Allen’s insult. She said Fassie looked like a horse and Fassie never forgot it.

Fassie told Lara Allen the press was “… all rubbish. They just wanna get rich by writing shit about Brenda. I’m a money maker, newsmaker, life goes on.” By all accounts Fassie in fact courted the media and though she told Allen that what mattered was her music and Allen cursed herself for choosing such a difficult subject; was nonetheless intrigued.

“For five years running Brenda won the South African music award for the best selling album in the year of its release, and the album that featured Vulindlela was the first South African album to go platinum on the day of its release. She sold more than any other South African musician and is reputed to have earned more than six million in royalties in the last eight years of her life alone. Brenda is widely credited as fundamentally influential in the birth of kwaito, and when her 2000 album Noma Kanjani went platinum the press started calling her SA’s Kwaito Queen. She was in and out of rehab, could not kill her crack habit and wound up with brain damage, dying on 9 May 2004, with President Thabo Mbeki addressing 20,000 mourners at her funeral in Langa Stadium.”

Fassie was conscious, she facilitated pride, liberated South Africans from the stifling claustrophobic and unformed vision of themselves, encouraging them to reach their full potential in her own unusual and creative way.

Njabulo Ndebele saw in Fassie a free spirit, experimental and innovative. He writes that “the obliteration of the divide between the private and the public is at the bottom of her verbal ungovernability…She brought sexual preference into the public arena, and what she brought, her honesty and her expression, is what we need.” Ndebele’s essay illustrates just how the media used the gift of her loose tongue and her “unmistakable outrageous brazenness.” He tracks the headlines, reflecting a genuine discovery of a major musical talent. Bona magazine’s prediction after her dramatic debut into the entertainment industry in 1984, “There’s no stopping Brenda”, was not to be realised for long. Listen again to Noma Kanjani; listen to Soon and Very Soon. There is indeed “no more dying there”. Lionel Manga knows that her music is of the essence. His resignation crystallises my own feeling: “She came as a vivid soul to be somewhere in the limbo, to be where she has been and nothing else. Her fame was therefore her fate.” DM

I’m Not Your Weekend Special; Portraits on the Lifestyle and Politics of Brenda Fassie, edited by Bongani Madondo (Picador Africa)

Photo: A file photo dated 29 November 2003 shows South African pop icon Brenda Fassie performing at the OppieKoppie Urban Music Festival at the Tshwane Showgrounds in Pretoria, South Africa. EPA/STR

Become an Insider

Become an Insider