World

Ariel Sharon, Apartheid South Africa and mutual military interests

The death of former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon has renewed debate about his legacy, but there’s been little on its South African component. By HENNIE VAN VUUREN and ANINE KRIEGLER.

Even among Israelis, Sharon has long been a controversial figure. A career soldier, considered a brilliant strategist, but one with a history of insubordination, he brought to both his military and later political life a leadership style that would rightly be termed reckless, were it not so often rewarded with success.

His place at the centre of almost every key military moment in Israel’s bloody second half of the twentieth century earned him the title of war hero, while his role in two civilian massacres (one of 69 people in a village in the West Bank in 1953, another of as many as 3,000 in a Lebanese refugee camp in 1982) earned him the moniker of ‘the Butcher’. He was instrumental in developing the Israeli policy of guaranteeing swift, violent reprisals for any attack on Jewish life.

His subsequent political record is similarly divided. For his negotiation style, particularly as Minister of Housing in the 1990s, he received another epithet – ‘the Bulldozer’ – before a stroke ended his career as Prime Minister in 2006.

While some South Africans have expressed their admiration for Sharon (who visited South Africa numerous times before becoming Prime Minister), there has been little reflection since his death on Sharon’s place in the relationship between the two countries, particularly during the highly militarised final decades of Apartheid rule.

The military alliance between the two pariah states was largely covert, but, according to reams of correspondence between the respective defence ministries, unreservedly supportive and warm. Sharon played a key role in keeping it so, going further than most in publicly asserting South Africa’s urgent need for more and better weaponry. There was a clear sense of parallel between the struggles of the Apartheid and Israeli states, and although many Israelis were at pains to maintain their ideological distance, Sharon was not among them.

Much of this is lucidly illustrated by Sasha Polakow-Suransky in his book The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s secret relationship with Apartheid South Africa. From 1977 (the year the UN Apartheid arms embargo came into effect) into the 1980’s, South Africa was Israel’s largest weapons customer. This provided much-needed foreign currency for the Israeli state in return for intelligence exchange, technology, ships and aircraft, and ultimately co-operation in the development of nuclear weapons.

A surprising measure of Sharon’s controversial legacy is foreshadowed in a 1982 SADF memo to South African Defence Minister Magnus Malan, providing a CV and character assessment of his new Israeli counterpart.

The last of the document’s nine pages, translated from Afrikaans, reads:

Guidelines for cooperation with Sharon

32. Background. Sharon’s behaviour should be carefully weighed. On the one hand, he is an impulsive politician apt to make drastic, far-reaching decisions on the spur of the moment. On the other hand, his reputation in dealings with other countries is highly impressive. He always maintains a cool head in the Knesset and largely succeeds in maintaining the image of an eminent politician and statesman. He succeeded, for example, in negotiating many positive and mutually acceptable measures with Egypt in connection with the withdrawal from Sinai. The Americans not only have great respect for him, but seem to like dealing with him. (His standing invitation to visit the US speaks for itself). Furthermore, it is clear that [then Prime Minister, Menachem] Begin trusts him to handle virtually all highly sensitive matters…

33. Guidelines. In light of the above, it may be desirable in dealing with Sharon to practise principled, honest position statements without offending him. A policy of “do not beat around the bush” seems to be his preference. Creating false hope/expectations that later turn out to be unfeasible, could be counterproductive. Sharon’s actions and methods should not be dismissed as irresponsible or impulsive as he has demonstrated on several occasions that he has qualities that can make him a strong leader in the political/diplomatic arena.”

The South African approach seems to have paid off and Sharon, like others in the Israeli military establishment, developed close ties with the Apartheid securocrats.

Sharon secretly visited South Africa as Defence Minister in 1981 and spoke to South African forces along the border of Angola.[1]

South African troops had by then repeatedly invaded and commenced occupation in part of Angola – in support of the CIA-backed Unita rebel movement. Sometime shortly after that, Sharon visited Washington and according to a report by the New York Times:

“Sharon, in company with many American and NATO military analysts, reported that South Africa needed more modern weapons if it was to fight successfully against Soviet-supplied troops.”

While a vast amount of money was wasted on weapons that were never used during the Cold War, various Southern African countries experienced real conflict. In August and September 1981, just as Sharon took office as Israeli Minister of Defence, the South African Defence Force invaded Angola in what it termed ‘Operation Protea’.

This was by far the biggest battle in the war between South Africa and Angola resulting in massive bloodshed: almost 1,000 Angolan and SWAPO soldiers were killed while 10 SADF soldiers died. To achieve this, the regime in Pretoria mobilised 142 aircraft, including Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) used for reconnaissance.[2] These drones were developed in South Africa but based on similar drones purchased from the Israeli Aircraft Industries (IAI).[3]

Some reports suggest that this was the first use of modern drones in military conflict.[4] The IAI Scout drone was subsequently deployed by the Israeli Military during the 1982 Lebanon war.

“…Wish to thank you for the friendly and understanding way”

Following the 1982 Lebanon War, mass protests in Tel Aviv led the Israeli government to establish the Kahan Commission, which found that Sharon, as Minister of Defence, bore “personal responsibility” for “the massacre by Lebanese militias of Palestinian civilians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila”. The commission recommended that he resign, which Sharon did with great reluctance on 14 February 1983.[5]

Among, his allies, he could count on the Apartheid regime.

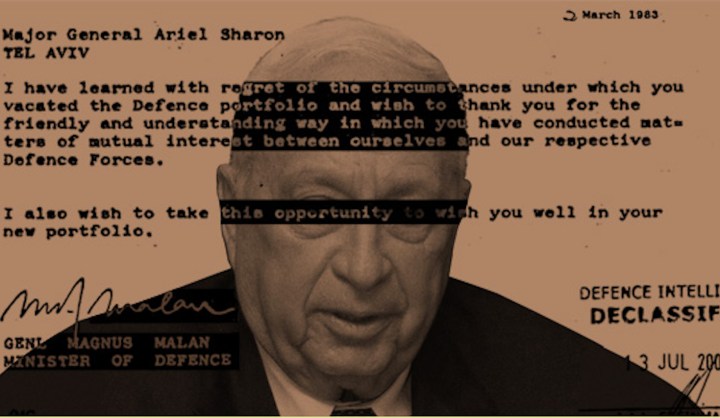

Magnus Malan wrote a letter to Sharon two weeks later (2 March 1983), expressing:

“regret of the circumstances under which you vacated the Defence portfolio and wish to thank you for the friendly and understanding way in which you have conducted matters of mutual interest between ourselves and our respective Defence Forces.”

Sharon responded on 20 April 1983, thanking Malan for his letter making the point that “I am sure that the understanding between our countries will develop for our mutual interest.”

Photo: The letter from Sharon to Magnus Malan

There can be little doubt that this relationship between the Apartheid military establishment and their counterparts in Israel did in fact deepen as a mix of money and ideology smoothed over other concerns. Israel was one of the most important allies in South Africa’s weapons procurement during the brutal years of PW Botha’s regime. However, Israel was by no means alone in selling weapons to South Africa – which many countries and corporations continued to do in contravention of international sanctions, earning a fabulous profit through inflated ‘premiums’. This is an aspect of history that many wish to erase.

The life story of men like Ariel Sharon and the ‘mutual interest’ shared with the South African Apartheid are open secrets. They deserve far more attention if we are to fully understand the present. DM

Hennie van Vuuren and Anine Kriegler are Research Associates with the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation. They are working on a project on transitional justice and economic crime in South Africa- Open Secrets. This feature originally appeared in Open Secrets www.opensecrets.org.za. Follow them @OpenSecretsZA

[1] Southscan. Itemised Account of relationship between Israel and South Africa, Vol 2, No. 26., 16 March 1983

[2] Scholtz, Leopold. The SADF in the Border War 1968-1989. Tafelberg, 2013

[3] See the South African Air Force Museum Website

[4] See: Zaloga, Steven (19 July 2011). Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Robotic Air Warfare 1917–2007. Osprey Publishing. p. 22. As quoted in Wikipedia: Israel-South Africa relations

[5] Wikipedia – Sabra and Shatila Massacre

Photos: Open Secrets

Photo1: A document declassified by the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) in 2006 and available here

Photo2: The letter from Magnus Malan to Sharon

Become an Insider

Become an Insider