Africa

Mohamed Morsi and the likely end of the Camp David Accords

For the moment, Egypt’s president-elect seems to be abiding by the principles of the Camp David Accords and maintaining the peace with Israel. But the region is very different now from what it was in 1979, when the treaty was signed—and the pressure Morsi faces from both his voter base and his comrades in the Islamic world could prove too much to bear. By KEVIN BLOOM.

In early February last year, more than a week before Hosni Mubarak resigned as president of Egypt, former Israeli minister of foreign affairs Moshe Arens wrote a column in Ha’aretz. In it he argued that it is easier for Israel to make peace with a dictator than with a democratically elected president. To back up his thesis, Arens cited the only two lasting peace treaties that his country had concluded thus far—one with Egypt under Anwar Sadat, the other with Jordan under King Hussein.

Arens went on to note that, although territorial concessions had appeared to be the main driving force in Israel’s peace agreements with its neighbours, the fundamental requirements for a deal have always been the following: first, that the treaty put an end to any further territorial claims and thus effectively end the conflict; second, that the signatory be able to combat and quell any internal terrorist activities directed towards the state of Israel.

Noted the longstanding member of Israel’s centre-right Likud party: “These are conditions that a dictator, if he so wishes, could conceivably satisfy.” Why? Because a dictator’s decisions will of necessity dominate public discourse, Arens explained, just like his security forces will of necessity quash any violent actions that are deemed against his nation’s best interests.

At the time of the column’s publication, the fear of the majority of Israelis was that the Mubarak regime—which followed on philosophically from the regime of Sadat—would be replaced by a democratic dispensation that elevated anti-Israel Islamists into power. Would such a regime negate the Camp David Accords signed between Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin in 1979?

With the victory of Muhammad Morsi in the recent Egyptian elections, and the official proclamation of his ascendancy to the presidency on 24 June, that fear became a reality. Not least because the new Egyptian head of state, for years the Muslim Brotherhood’s hard-line enforcer, first entered his country’s political scene as an opponent of the peace treaty with Israel.

Back then, Morsi was a teaching assistant in the faculty of engineering at Cairo University. He would soon move to America, earning a PhD from the University of Southern Californian and working as a professor at the University of North Ridge. After returning to Egypt in 1985 to teach at Zagazig University in the Nile Delta, he became a leader in the Muslim Brotherhood and—from 2000 to 2005—one of its first members in the Mubarak-dominated parliament.

Morsi was chosen by the Brotherhood’s top authorities to lead its parliamentary bloc, and was consequently a key figure in the group’s introduction to multiparty democracy and coalition building. Nevertheless, in subsequent years, from his position on the Brotherhood’s governing board, he gained a reputation as a leader who brooked no internal dissent.

In 2007, when the Brotherhood adopted a hypothetical party platform that referred to Islamic tenets in stating that neither a woman nor a non-Muslim could be eligible to serve as president, Morsi was a chief defender of the position.

The only leader in Egyptian history to rise to power on the back of a democratic election—he took 52% of the vote against 48% for former Mubarak official Ahmed Shafik — Morsi is therefore a man of profound contrasts. During his campaign, despite his stance in 2007, he said he would support women’s rights if he won.

He also said as part of his campaign that he would support peaceful relations with Israel, even though he has been known to label Israeli leaders “vampires” and “killers”. Further, during his campaign Morsi attended rallies where anti-Israel rhetoric was commonplace, including one such rally where a Muslim cleric promised the crowd that the candidate would liberate Gaza and create an Islamic caliphate with Jerusalem as its capital.

Stories like these, according to Newsweek’s Jerusalem bureau chief Dan Ephron, “reinforce the notion among Israelis that even if the peace deal with Egypt remains in effect, Morsi will be hostile and antagonistic. Already, they say, the Brotherhood is drawing Egypt closer to Hamas than ever before. Given Israel’s fallout with Turkey two years ago, the Jewish state is now more isolated in the region than it has been in decades.”

From a historical perspective, it’s important to mention in this regard that David Ben Gurion, Israel’s founder and first prime minster, hung his country’s future in the region on its relationships with non-Arab nations, primarily Iran and Turkey. Ben Gurion’s theory was that by keeping Iran, Turkey and Egypt apart, Israel could survive. Now, for the first time since 1948, Israel is faced with the fact that all three of these countries are led by Islamic hard-liners.

What’s more, the celebratory gunfire in Gaza on Sunday night, during which one Palestinian was killed and three others wounded, underlined the concerns of Israeli officials with respect to the most volatile of its “territories”. Echoing the sentiments of his people, Ismail Haniyeh, head of the Hamas government in Gaza, welcomed Morsi’s victory as a major step in the direction of Palestinian freedom.

Unsurprisingly, what seems to be maintaining the status quo for the moment is Egypt’s Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which last week blocked any change in the Rafah border-post situation by removing foreign policy from the new president’s authority. Meaning, Morsi can’t act quickly to break Israel’s blockade of Gaza by opening the crossing point, and that Egypt’s restriction of the movement of goods and people—in co-operation with Israel—will remain.

That said, according to an interview published by Iran’s Fars news agency on Monday, Morsi wants to “reconsider” Egypt’s peace deal with Israel and build ties with Iran to “create a strategic balance” in the Middle East. “We will reconsider the Camp David Accord,” Morsi was quoted saying to a Fars reporter in Cairo on Sunday, just before his election triumph was announced.

On Monday evening, Morsi’ spokesman denied that the interview with Fars took place, stating: “Everything published by this agency is baseless.” But whether Morsi made the statement or not, one thing is clear: when it comes to Israel the Islamic world expects Egypt’s president-elect to act in a certain way, and the pressure on him to deliver in the medium term will be immense.

In a widely syndicated article, Dr Liad Porat, one of Israel’s leading experts on the Muslim Brotherhood, provided his views on how things are likely to play out.

“Porat believes in a slippery slope in which Egypt, without cancelling outright its treaty with Israel, will slowly become the principal agent inciting against it on the international stage,” the article noted. “He thinks Egypt will reduce its relations with Israel to the bare minimum required to maintain its ties to the United States, which provides Egypt with $2-billion in annual aid.”

“’I think eventually (Morsi) will bring it to a popular vote,’ (Porat) said about Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel. ‘And of course, it will be phrased as he wants to phrase it.’”

All of which intrinsically endorses the column published in Ha’aretz last year by Moshe Arens. Though it doesn’t stand as a feather in Israel’s cap that it can only make peace with dictators, the realpolitik of the situation is plain: Morsi, as the first democratically elected president in Egypt’s history, is going to have to make decisions that keep his ratings high.

And, as he well knows, if there’s one thing his constituency isn’t shy about demanding, it’s a strong position on the state of Israel. DM

Read more:

- “Morsi’s Win in Egypt Sparks Fear in Israel,” in the Daily Beast

- “Israel’s worst nightmare: Egypt’s new president elect,” in the GlobalPost

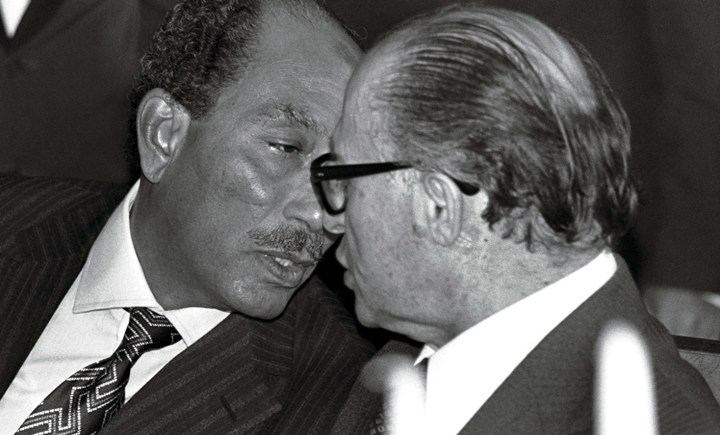

Photo: Egypt President Anwar Sadat (L) head to head with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin in 1977 when Sadat made his historic visit to Jerusalem, becoming the first Arab leader to visit the Jewish state since its birth in 1948. Sadat and Begin went on to hold secret talks at Camp David with United States President Jimmy Carter and eventually signed a peace treaty in March 1979. (REUTERS)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider