Africa

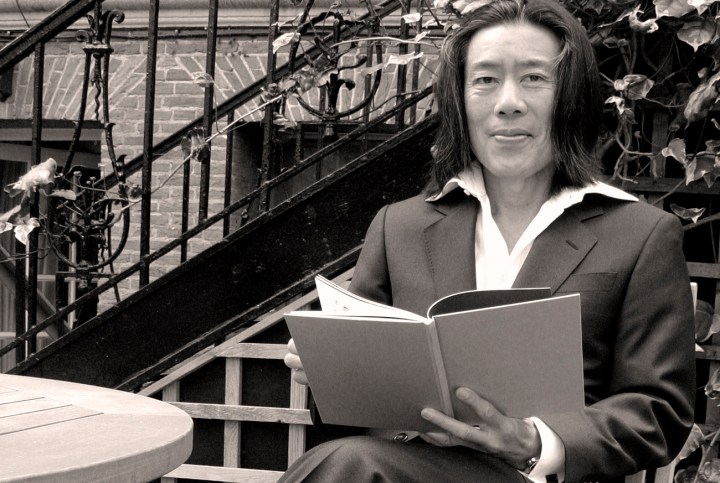

A conversation about southern Africa with Stephen Chan

Author and academic Stephen Chan has some firm opinions about politics in southern Africa over the last decade or so. And he maintains South Africans can't fully understand our own history until we start paying more attention to that of our neighbours – Zimbabwe in particular. By THERESA MALLINSON.

For anyone interested in southern African politics, Stephen Chan’s latest book, Old Treacheries, New Deceits, is required reading. Labelling it “required” doesn’t mean it’s boring: Chan peppers the book with personal anecdotes from time spent in the Commonwealth Secretariat back in the 1980s, and it’s clear that he’s privy to inside information regarding South Africa’s mediation in Zimbabwe.

The time Chan has spent living in various southern African countries over the years – not to mention his extensive research about others – means that he’s able to view the region from a bird’s-eye perspective, able to attempt to illuminate some of the complex connections that those of us living on the ground don’t always the time to explore.

Chan says his first trip to Africa was accidental. “I was working for the Commonwealth Secretariat in London, at the time of Lancaster House conference that agreed on independence for Zimbabwe. I was a very, very young junior official; I did the paper clips on the documents. After it was over I thought that was the end of it and took leave… I just thought, ‘thank god, Christmas holiday’. And I came back and there was a note on my table saying ‘don’t unpack, you’re leading the reconnaissance group to Rhodesia’, as it then was. So I anchored the Commonwealth observer process in the Matabele land provinces for the three months in the beginning of 1980 until independence came, and just hung around after that.”

It was after time spent in the early 1980s at the Commonwealth office in Uganda that Chan decided to make the switch from officialdom to academia. “Uganda… was one of the assignments as part of the Commonwealth job, and this was the tail-end of the clean-up after the fall of Idi Amin. All the big ministries had already been reconstructed… no one was interested in doing the ministry of social development and youth affairs. They gave me that… I went to quite a lot of the wild lands where the war was still going on (and) just saw the real destruction and destitution of it all and thought official international life wasn’t getting the full picture, so I decided to leave and become an academic so I could write about it fully – only to discover that the academic world didn’t give the full picture either. It’s been a constant struggle. But I have more freedom as an academic than I did as an international official, obviously.”

While Chan is a well-respected academic, and professor of international relations at the School of Oriental and African Studies, he feels it is important to also write for a lay audience. “I want to tell a story that people can read. It has to be a complex story, you can’t dumb down the content, even if you simplify the worlds. But I am rather sick of academics just talking to other academics, otherwise why do all of this? A lot of my field research has been pretty risky stuff, so why tear your hair out… unless you have something to say to ordinary people, and ordinary readers.”

Although Chan is based in London, he comes out to southern Africa every year. He visits other parts of the continent as well, but chiefly focuses on the south. “I just like this part of the world,” he says. “There are many problems here which are very interconnected, and one of the reasons for writing the book, for instance, (is that) people here in South Africa, although they’re very knowledgeable about the frustrations and difficulties of taking this place forward, seem to have no knowledge or even any deep interest in surrounding countries.

“When I was living in Lusaka in the 1980s all the liberation groups like the ANC were in exile there… There was a lot of stuff going on which contributed to the final liberation of this country, but could not have happened without having that base in Zambia. If you go down the streets here and ask anybody ‘what do you know about Zambia?’ the answer is almost inevitably ‘very, very little’ – I think it’s a pity.

“This country caused immense damage to the surrounding region. And I think it’s quite natural for a process of denial and ignorance to be commonplace. You’ve got to be very, very careful that you’re not like the Japanese are with the Chinese, and absolutely repudiate the truth of what happened. The truth of what happened was really very profound for many of the surrounding countries, Angola and Mozambique, in particular, and to a more limited extent in Zambia.

“South Africans even tend to misunderstand the complexities of a country next door like Zimbabwe, for instance. So key linkages in the book are really about trying to explain about what went on in the relationships between those two countries, and then Zambia as a third party from the liberation days,” he says.

One way in which Chan brings our recently-lived history back to life, is by focusing on the personalities of Mbeki and Zuma; Mugabe and Tsvangirai. Regarding his approach, he says he doesn’t believe in “this goodies and baddies nonsense”. Speaking of Zimbabwe, he calls himself a staunch critic of Mugabe, but is cautious not to completely vilify him. “I’m very well known in Zimbabwe for not pulling any punches. But even so it doesn’t help to demonise somebody – even your worst enemy you have to try to understand.” On the other hand, as Chan phrases it: “Even the goodies make mistakes”. About MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai, he says: “My friend, the prime minister, has made quite a number of mistakes as well, and I’ve said as much.”

Commenting on Mbeki’s mediation in finding a compromise peace deal for Zimbabwe, Chan is even-handed. “To be fair to President Mbeki – and I have said he got it wrong – I’m not sure anybody else could have got it right, it was such a complex issue. But I do think that the final settlement was wrong. I do think Prime Minister Tsvangirai should have been the president. I have no problem with a power-sharing government, but the wrong man became the president. The principle of inclusiveness is fine, but democracy still has got to be reflected in that.”

As Zimbabwe is set to vote again next year, Chan’s book provides a useful behind-the-scenes look as to just went down in the 2008 elections. As well as focusing on Mugabe and Tsvangirai, he provides insights into the machinations of the Mujurus (Joyce Mujuru is the deputy president, her husband, Solomon, who died in a fire last week, was also a powerful force within Zanu-PF); Simba Makoni, who ran as an independent presidential candidate after leaving Zanu-PF and Arthur Mutambara, who led the breakaway faction of the MDC.

If you need a refresher course in contemporary southern African history and politics, Old Treacheries, New Deceits will get you up to speed – and send you scurrying to check out Chan’s prolific back catalogue for further insight. DM

Read more:

- Stephen Chan’s website.

Watch more:

- Interview with Stephen Chan by Think Africa Press.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider