I grew up in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, spent over four years living in Texas, and typically return to my homeland to visit on an annual basis.

During all of the decades I have spent in Canada and the US, I encountered a police road block only once. As Tim Cohen might say, I am not making this up!

And that road block had an air of excitement around it! I reckon I was about seven or eight years old at the time and there had been an armed bank robbery in my hometown of Dartmouth – such incidents there being as rare as police road blocks – and the bandits made off with their loot Hollywood-style in a get-away car.

With my father at the wheel and my mother in the front passenger seat, I sat wide-eyed in the back seat as a unformed cop briefly peered inside and decided that my parents and I were not persons of interest in the caper. It remains vivid in my memory because it was such a rare event in that neck of the woods.

I mention this incident because one of the many sensible proposals outlined by Leon Louw in Cohen’s new book – Leon Louw: A Legacy of Solutions – is the abolition of police road blocks in South Africa.

In the US and Canada, traffic police are expected to do their jobs and nail those who break the rules on the road on the spot without annoying the law-abiding majority. But in SA’s failed state, the thirst for cooldrink is insatiable.

“These (road blocks), Louw argues, are a theatre of futility – unlawful under the Traffic Act, costly, bribery-prone, and a road hazard in themselves. They delay drivers, who then speed recklessly to make up lost time,” Cohen writes.

“The real task of traffic police, he says, is to target actual dangerous driving in real conditions, not to entrap motorists on empty state roads. But that would require discretion and judgement ...”

Louw has actually been arrested at roadblocks because he will not show his driver’s licence until he sees a warrant and is informed if it is a traffic or police action. This is a man committed to his cause!

Free Market Foundation

Louw founded the Free Market Foundation (FMF) in 1973 and lead it for five decades until his acrimonious departure. I knew shockingly little about Louw or his overlooked role in the anti-apartheid movement and contribution to the crafting of SA’s progressive Constitution until I read this book.

Cohen has done a service to history by shining a light on Louw’s record and legacy, and he has done so in his typically readable and witty fashion.

I was also intrigued to learn that Louw had been a communist before his embrace of free markets. Veteran journalist Martin Creamer told me this while he and I were on a recent press junket and I had mentioned that Cohen’s book on Louw was about to be released.

“Back in the 80s, Louw took me on a tour around Soweto and he said ‘they need to build factories and industry here’. And he was a communist before that!” Creamer said.

Indeed he was, and Cohen relates that the scales were peeled from Louw’s eyes when he witnessed the police slaying of a Johannesburg street trader in the 1960s. Louw has since been a crusader for the right of such business people to hawk their wares where they and their customers see fit – and he has been a crusader on many other fronts as well.

One of the things this reader found striking about Louw’s conversion is the juxtaposition with the late David Horowitz, who was a radical US New Leftist and Marxist in the 1960s.

But Horowitz’s transformation took him down a sinister path – his (dubiously named) “Freedom Centre” and its online “news site” Front Page Magazine are far-right, rabidly racist outfits that had a huge influence on Trump minion Stephen Miller and continue to shape much of Maga’s fascist mindset.

Horowitz and his movement became apartheid apologists, demonising Mandela while worshiping Trump as an agent of divine providence. It is an example of how a rejection of Marxism can lead a former follower down the crooked path to fascism.

Louw’s trajectory is by contrast a noble one and a useful reminder that the anti-apartheid movement and the ideas and ideals it spawned could flow down many diverse channels and rise to a more hopeful vision of the future.

It is also a reminder – on SA’s polarised political stage with its often misleading portrayals of opposing views – that an embrace of free markets does not make a person “anti-poor”.

You may disagree with some or many of Louw's policy proposals, but reading this book leaves me with an abiding impression of a man with a deep well of empathy and commitment to human dignity.

This book is brimming with Louw’s ideas, and his influence literally spanned the world from Malta to far-flung regions of post-communist Siberia.

For the sake of brevity, I am going to unpack just a couple here.

‘Banality of the land debate’

One is the “banality of the land debate”.

“The common mantra,” Cohen writes, “is nothing has changed – but conditions range between two and 27 times better than in 1994. Louw sees this as representative of the extraordinary accomplishments of black people countrywide.”

We in fact don’t really know the racial breakdown of land and home ownership in SA but it is not nearly as skewed as the likes of the EFF and MK parties would like their followers to believe. Louw’s new outfit the Freedom Foundation is undertaking the first comprehensive survey of South African wealth, including land – its findings, I am sure, will be fascinating.

Louw has also long been a passionate advocate for providing the poor with title deeds to unlock what the astute Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto has termed “dead capital”. Among other things this could bring much-needed economic vitality to the former homelands that remain largely impoverished rural relics of apartheid.

It’s also an approach, it must be said, that has strong support across the political spectrum, with a couple of notable exceptions among the Gucci Marxist crowd.

Louw also has very libertarian views on the issues of tobacco and alcohol consumption, rooted in ideas of personal freedom. This is an area where politicians who like to position themselves on the “progressive left”, such as Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, betray the socially conservative bent they share with the likes of the White Christian Nationalists behind Trump’s Maga movement.

Read more: Prohibition – social conservatism that’s shattering working class lives

Dlamini-Zuma’s draconian banning of alcohol and tobacco sales during the initial pandemic hard lockdowns was rooted in a history that is both racist and classist – and an infringement on human choice and freedom.

Cohen relates a dinner that Louw once had with Minister of Health Aaron Motsoaledi in which the minister intoned “that he wanted to ban smoking, restrict sugar and salt, and make alcohol scarcer” on the ground that “they have no benefits”.

“Louw nearly fell off his chair. Smoking, he retorted, has many benefits: pleasure, relaxation, concentration, social confidence, relief from depression... To declare that millions of people derive ‘no benefit’ from something they plainly enjoy is not science but puritanism.”

Again, here is a space where Louw’s ideas straddle the political spectrum: opposition to what many on the Left have rightly viewed as “social control”. This also extends to issues such as abortion and gay marriage.

Indeed, for decades the Free Market Foundation wisely chose a non-partisan and apolitical approach in a bid to objectively influence whatever government happened to be in power. (Its about turn on this front was a key reason for Louw’s departure, which Cohen narrates in a brief section.)

And many of its ideas – perhaps surprisingly to some – have appeal to a range of political parties and ideological views.

There is much more in this crisply written book that provides plenty of engaging food for thought, including the questioning of assumptions about inequality and SA’s real unemployment rate – and the reasons why so many people find themselves hustling in the informal fringes of the economy.

Disclaimer: I must add that Cohen – or I should say Tim – was my editor for years at Business Maverick. Tim is a good friend who I have discussed many of these ideas with over the years over a few drinks – no benefits, ha! – and around campfires on the Orange River on a fly fishing trip.

Readers can decide for themselves whether or not this makes me an objective reviewer. But I can honestly say I enjoyed this book and found it enriching. I think you will as well. DM

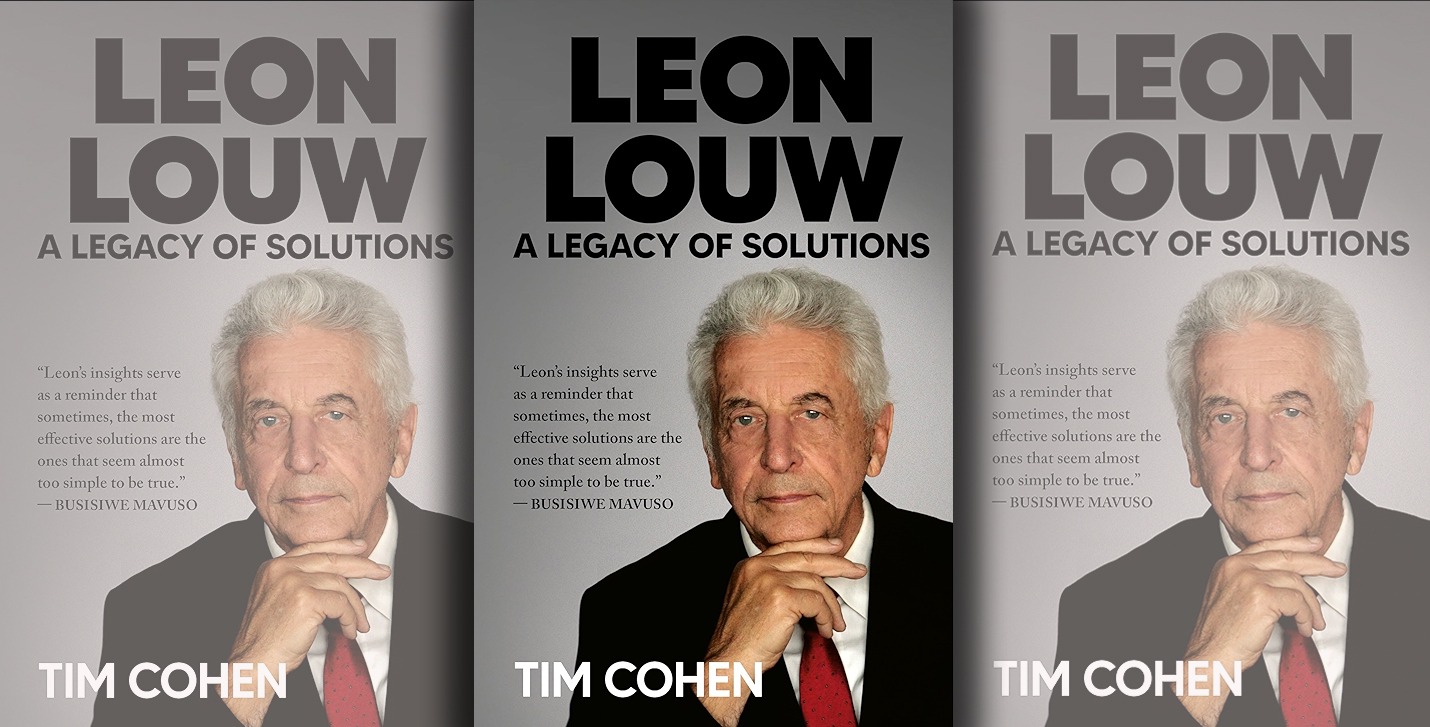

Tim Cohen discusses Leon Louw's legacy in this fascinating book. (Publisher: Maverick 451)

Tim Cohen discusses Leon Louw's legacy in this fascinating book. (Publisher: Maverick 451)