/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/label-analysis-2.jpg)

While the headlines of the moment are concerned, correctly, with the corruption and turmoil in the leadership of our police services, this may turn out to be an important moment for our formal politics. Current dynamics, along with some very recent events, may now be driving the final nail in the coffin of public interest in our politics. And the result will be that the government gets weaker while other institutions grow stronger.

There can be no doubt that public interest in our politics, and our politicians, has been waning for many years.

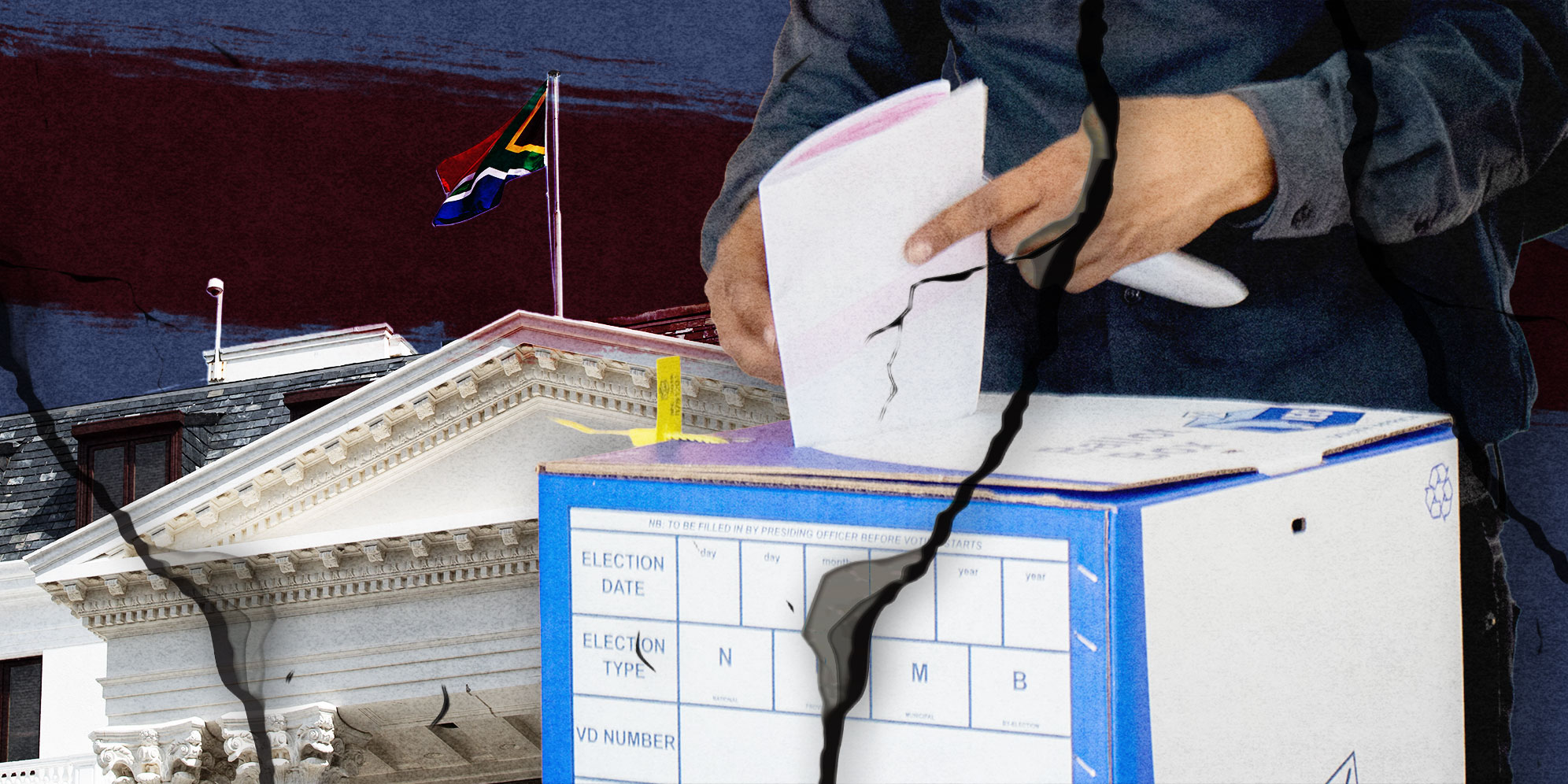

Election after election has seen much hand-wringing at the fact that real voter turnout – the number of people who are allowed to vote versus those who actually do (rather than the number of people registered to vote with the Electoral Commission) has been declining.

It may seem intuitive that as our politics becomes much more competitive, with many more players catering to many more constituencies, there would be more interest in politics.

In 1999 there was no chance the Democratic Alliance (DA) or any other party would provide a proper challenge to the African National Congress (ANC). This is not the case now, where the coalitions that will take over after an election can be difficult to predict.

At the same time, our needs have become incredibly urgent.

The future of Joburg as a viable city could hang on the result of this election, and the likely coalition that governs after it.

And yet all of the available evidence suggests that the percentage of people who vote will continue its fall in next year’s elections.

While it is entirely rational to demand that people vote, considering our history and the huge sacrifices that were made to ensure this right for all South Africans, people cannot be forced to vote.

And considering their options, they cannot be blamed either.

Consider the state of our major parties, and the way they have behaved.

The ANC has almost become defined by corruption. Despite its various promises of “renewal”, the fact that people such as David Mahlobo or Malusi Gigaba can continue to represent it shows nothing has changed.

Just last week a report found that the ANC’s deputy mayor of Tshwane, Eugene Modise, receives money from a security company that has a contract with the city.

Considering he is in office through a coalition in which ActionSA provides the mayor, this may well implicate Herman Mashaba’s party as well.

At the same time, while the ANC cannot afford to lose President Cyril Ramaphosa as its leader at this moment, it is entirely possible that the Phala Phala scandal will return to haunt him.

The Constitutional Court has still not handed down judgment in the claim that Parliament was wrong to not follow the recommendations of its independent panel into Phala Phala. Considering the weakness of Ramaphosa’s explanations for keeping foreign currency in a couch, it is entirely possible the court makes a finding that reopens this process.

Meanwhile, the uMkhonto Wesizwe party is beginning to closely resemble a circular firing squad.

Its leaders appear determined to fight with each other, while one of its now-former MPs, Duduzile Zuma-Sambudla, is implicated in selling members of her family to fight for Russia in Ukraine.

Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters seem to have also lost the political initiative.

In the past, the DA would have stood to gain from all of this.

As Dawie Scholtz has explained, in the past there has been a big voter differential in terms of race (in the last national election 73% of white people voted, while 55% of black people did; and in previous elections, it has been greater, particularly in local elections).

While there may be many reasons for this, one simple explanation may be that many former ANC voters felt there was no one for them to vote for, while DA voters were energised because of how they feel about service delivery.

But recent events in the DA have shown the party may now be losing its claim to be free from corruption.

The revelation that its leader John Steenhuisen was misusing the party’s credit card, along with the unresolved dispute over the removal of Dion George from the Cabinet may all create the impression the party is not as clean as it was.

Of course, the processes around this are not yet resolved, and it may well be that either new facts emerge, or the DA concludes this in a way that demonstrates it can act against corruption.

But unless it achieves that, it may well turn out that the DA is no longer seen in the way it once was.

This may mean that an important constituency no longer believes there is a party for them.

In the end, it appears the number of people who believe there is no one worth their vote is only going to rise.

This in turn means that the legitimacy of the government is undermined, and in the longer run, for various reasons, the government itself becomes weaker.

This then creates space for other institutions to grow relatively stronger.

The first example of this is obvious.

Taking the gap

As the state has grown weaker so it has allowed the private sector, companies, to enter the gap. More and more, the government is coming to almost rely on companies to provide services previously provided by the state.

This process is likely to continue for many years to come, whether it be in providing electricity, managing Transnet or in other areas.

Meanwhile community groups and NGOs appear to be increasing their relative power as well.

In some middle-class communities, local groups are taking over the running of public facilities, such as swimming pools or even roads.

Then the rise of local vigilante groups, which have been active in many communities for many years, will continue.

It is very likely that a spaza shop owner, having caught a person stealing from them, will hand over that suspect to one of these groups rather than the police, simply because they want the theft to stop.

But these are not the only groups.

One of the more disturbing trends in the past few years has been the rise of corrupt men (they are almost all men) who profess to be religious leaders.

People such as Shepherd Bushiri (who stole millions before absconding to Malawi) or Timothy Omotoso (who despite the findings of a High Court ruling is clearly guilty of rape and abuse of young women) or Alph Lukau (who claimed to have brought a dead man back to life), have amassed huge followings.

They are able to do this partly because they peddle hope to those who receive very little, and often nothing, from the government.

In the process they end up with access to resources that often include weapons and armed men.

It is likely that still other groups will emerge seeking to take advantage of the vacuum left by a lack of interest in politics.

As much as our politicians may be lacking, the government matters.

And while those who are rich with loud voices might prefer a weaker government, a weaker government is almost always bad for the poor.

Unfortunately, this is a likely outcome of our looming season of political apathy. DM

SA and the upcoming season of apathy

SA and the upcoming season of apathy