Last week, the author and academic Jonny Steinberg suggested that there may well be important reasons why Cyril Ramaphosa has been so cautious since he became President seven years ago.

The implications of this are profound. It suggests that there are forces at work that have constrained him.

Obviously, it would appear most of those forces are in the ANC, and this thought process may devolve into a suggestion that he fears being removed from his position if he tries to reform the state.

As Steinberg points out, the consequences of this could be fundamentally destabilising to the state. It would, presumably, mean the end of the coalition between the ANC and the DA, and open the door to former president Jacob Zuma and MK.

The social strife this would create could affect our trajectory for decades. Steinberg is, of course, correct to raise this argument.

It also points out why Ramaphosa has been so slow to act. He has said many times that he wants the ANC to renew itself, and yet has done very little as leader to make this happen.

And yet, the balance of power may now, strangely, start to shift.

ANC constraints

The main reason that Ramaphosa might have refused to be assertive has clearly been the balance of power in the ANC. If he had overwhelming support, it would surely be easier for him to move.

The fact that so many people implicated in corruption were elected to leadership positions in the ANC at its 2022 conference (including people such as ANC chair Gwede Mantashe) suggests the balance of power in the party does not support his publicly stated renewal efforts.

It was surely this that led to Ramaphosa’s appointment of people like David Mahlobo to his government.

This, in turn, led to the intense pain that former Chief Justice Raymond Zondo has spoken of, at having to swear in people he made findings against at the Commission of Inquiry into State Capture.

More recently, Ramaphosa’s decision to fire the DA’s Andrew Whitfield suggested, to this writer at any rate, that perhaps he was under pressure in the ANC to act against the DA. The fact that he had to give in to this demand would suggest that he had to comply.

However, the dynamics in the ANC, which for the moment appear to be focused on the decision to work with the DA in national government, may be about to reset themselves.

Read more: ANC succession battle — the pros and cons of the top candidates vying for Ramaphosa’s job

It seems likely that the main issue will now be the race to succeed Ramaphosa at the ANC’s elective conference, due in just two-and-a-half years.

As has been pointed out many times, this is unprecedented territory for the ANC. For the first time since 1994, it is not clear which groups will support which candidates.

Instead of two or three clearly defined factions supporting certain candidates, there now appears to be a much looser collection of people who may simply follow their own individual interests.

It gives the impression that perhaps many people are still waiting to see who will gain momentum; they’re essentially looking for someone to support.

Of course, Deputy President Paul Mashatile has made it clear he has leadership ambitions. But consistent reporting by News 24 about his lifestyle, and the revelation that he has now declared that he owns a mansion in Constantia in Cape Town, with no explanation of how he could pay the R28.9-million it cost, suggests he is struggling to find momentum.

The coalition glue

At the same time, it is likely that the ANC will soon begin to appear weaker than it does now.

While it may still be dangerous to make predictions about the local elections (due next year or early in 2027), it seems likely the party will suffer a big decline in support.

Certainly, from public discussions in provinces like Gauteng, it appears that many residents are angrier than ever before at their circumstances. If they hold the ANC responsible for this, as is likely, it could well lose huge support.

This means that while the ANC would still be the biggest party in the national government, it would lack moral authority. And those who might oppose Ramaphosa might themselves lack public legitimacy.

At the same time, it should not be forgotten that when Ramaphosa has appeared to be assertive, he has received public support.

For example, his comment that the ANC was “Accused Number One in the dock” appeared to be welcomed by many voters.

If the ANC appears to become weaker, this might, strangely, open the door for Ramaphosa to be more assertive. His strength might turn out to be that he is the only person all members of the current national coalition will accept.

This means that for ANC leaders, there could be literally no one else in the party who could take over government and keep the current coalition in place.

If the local elections do show that the party is losing support (and this would become clear on the campaign trail long before the actual vote), those in the party might realise their only way to keep the power they have is for Ramaphosa to stay.

While it might be possible to form a coalition with MK, that would be highly dangerous and could lead to the ANC simply falling apart.

This means that Ramaphosa’s political authority (as damaged as it may be from incidents like Phala Phala) may suddenly be slightly stronger.

Read more: Reports link Cyril Ramaphosa campaign to shadowy figure at the heart of cop scandal

He could use this unique position to then implement whichever reforms he would like to.

And, if this is the case, it would be a harbinger of what is to come. It would show how the personality of the President would become much more important in the coalition era.

Of course, in our situation, it is foolish to make any predictions. But Steinberg is correct to raise the point that Ramaphosa might well have had good reasons for appearing to be so cautious.

But some of those reasons may soon fall away. DM

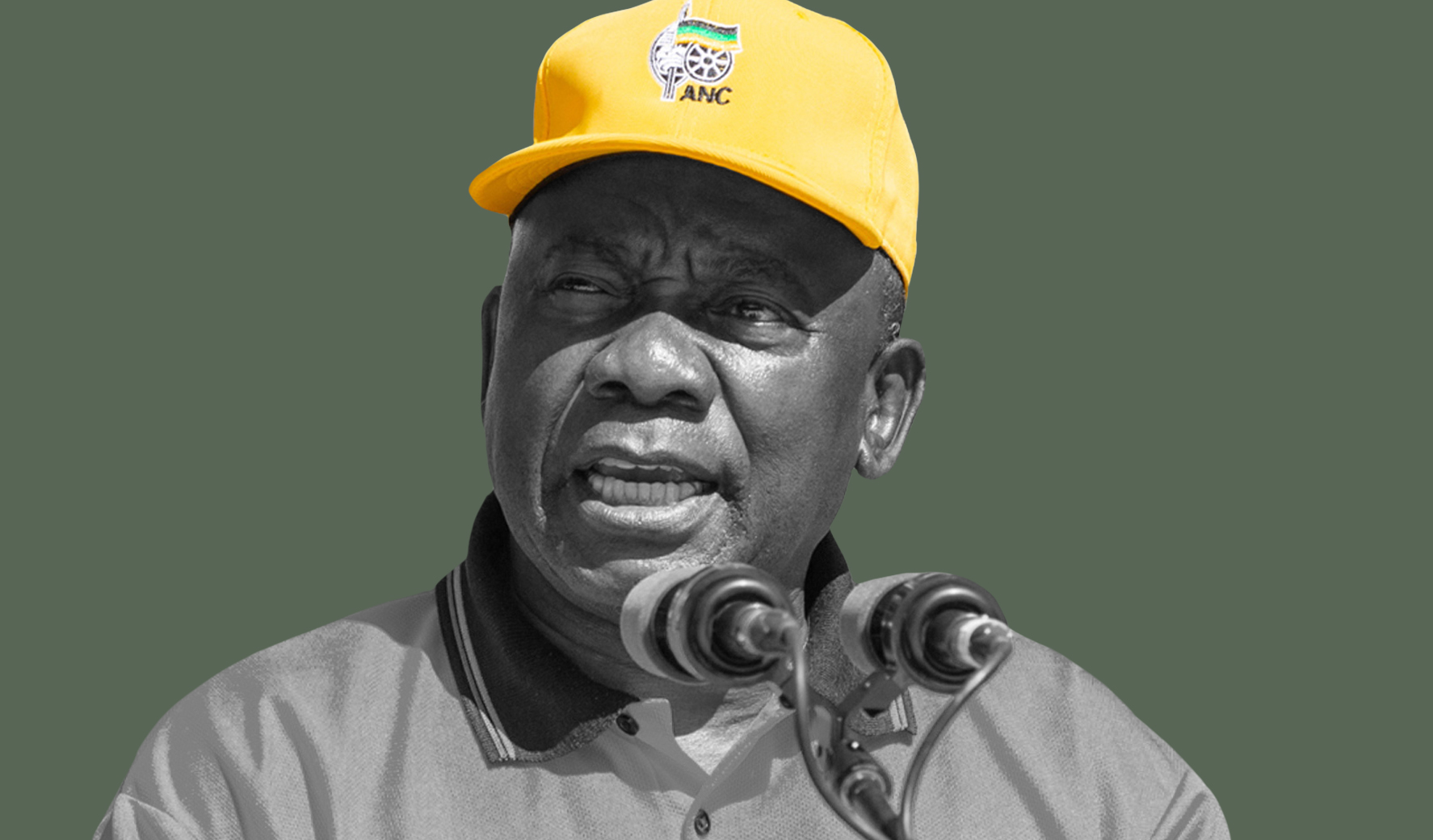

ANC leader, President Cyril Ramaphosa. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Yeshiel Panchia)

ANC leader, President Cyril Ramaphosa. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Yeshiel Panchia)