PHOTO ESSAY

Iraq’s water plight – the drought between two rivers

In October 2021, I arrived in Iraq’s southern city of Basra. Situated in the heart of the arid MENA region, Iraq is being ravaged by the soaring temperatures, drought and water scarcity characteristic of climate change. In this respect, it is but an acute representation of a global problem. But that is not all. It is also at the heart of what will only become an increasingly visible geopolitical problem: competition and control of natural resources.

Ninety-one percent of Iraq’s water originates in Turkey, Iran and Syria, leaving the country at the mercy of those controlling the taps upstream. Accompanied by a translator and fixer, I set out, travelling northwards from the very south, across the country, to explore the impact of these combined forces on those most directly affected – and what that might forebode.

Poisonous snakes emerge from fields and slither into homes in Iraq, threatening people and claiming lives. In neighbouring Iran, crocodiles previously known for their “blissful” nature are attacking the same people with whom they have peacefully existed for as long as anyone can remember.

Almost 120,000 people were sickened and admitted to hospital by contaminated water in Basra, Iraq. Large protests over water and electricity claimed 23 lives. Water protests roiled Iraq’s Kurdistan in August 2021.

In Iran’s Khuzestan and Aligudarz Provinces, at least three people were killed in July 2021, in weeks-long violent protests over water scarcity.

In Turkey, record-low rainfall led to warnings in January 2021 that Istanbul’s water supply was in imminent danger of running dry, while in May 2021 Turkish farmers blocked streets with tractors to protest against a water shortage which left crops shrivelled and animals without fodder.

Across the region, people abandon farms and migrate, stressing local metropolitan areas, losing lives to international migration and inflaming political instability.

This is not the scenario of a horror film, but the real-life consequences of climate change, of warming temperatures that are threatening all living creatures and exacerbating the competition for life’s most vital resource: water.

No country is spared, and natural resources know no national boundaries. But ultimately, each country does what is best for itself – regardless of its impact on neighbours.

Iraq is one of the world’s most water-stressed countries, ranked fifth in vulnerability to water and food availability and extreme temperatures in the UN Environment Programmes 2019 Global Environmental Outlook report.

Upland rice being picked by workers in Banihelan village, Kurdistan, Iraq, in October 2021. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

Temperatures have risen by at least 0.7℃ over the past century; extreme heat events are occurring more frequently. The World Bank estimates temperatures will rise 2℃ by 2050 while the average annual rainfall will decrease by 9%.

President Barham Salih, in a recent piece in the Financial Times, noted that desertification affects 39% of Iraq and “increased salinisation threatens agriculture on 54% of our land”.

Unicef reported in August 2021 that 60% of children in Iraq lack access to clean water, while half of schools have no water at all. With Iraq’s population of 40 million expected to double by 2050, demographic growth will exponentially worsen the situation.

Meanwhile, dams in neighbouring Turkey and Iran choke Iraq’s famed rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, in the heart of what was once known as the Fertile Crescent.

In October 2021, I embarked on a journey from Iraq’s southernmost point, travelling from the fishing community of Al-Faw at the Shatt Al-Arab estuary on the Persian Gulf up to the Iranian border in Kurdistan in the country’s north, exploring the impact of climate change and water scarcity along the way on those most directly affected.

It was a route of despair, as people abandoned desiccated farms for lives on the edges of unwelcoming cities in Iraq – or beyond. It was a route of anger and suppurating rage – at Turkey and Iran, whose dams finished off the few farms climate change had not yet entirely defeated, and at a government unable to force the two countries to open the taps.

It was a route of crisis, with Iraq expected to run out of usable water by 2025.

Wars about water have already started. The west is fighting Iraq over oil. Iraq is fighting for its survival (Anwer Nathar, geologist, Basra)

Mesopotamia, or the Land between the Two Rivers

The Shatt Al-Arab river – “the River of the Arabs” – begins in biblical paradise, formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers at Al Qurna, where Adam took the forbidden fruit from Eve and the famed Garden of Eden thrived on its waters – emptying about 200km south into the Persian Gulf soon after Iran’s Karun river joins the flow.

Water markers run up the side of the Darbandikan Dam, Kurdistan, Iraq, October 2021. The water level is at a low unprecedented in its 65-year history, which severely compromises the dam’s ability to generate power. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

It has been an artery of life for millennia, relied on for water for people, animals, agriculture and fish over its entire length, feeding the once fertile lands and bringing nutrients crucial to marine life in the delicate ecosystem of the Persian Gulf.

But today it is a very different story.

The level of water in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, both of which start in Turkey, is dangerously low, depleted by as much as 50% by the prolonged drought and elevated temperatures of climate change, and by the dams upstream in Turkey and Iran. The decreased level of freshwater has resulted in seawater intrusion as far as 150km upstream, drastically increasing the salinity of the river, ruining water supplies, agriculture and fish in both river and sea, and threatening the critical ecosystem on which the whole Persian Gulf itself depends.

Al-Faw

The sun has just risen over the estuary where the Shatt Al-Arab river empties into the Persian Gulf. Fishermen are unloading the morning’s catch from a half dozen pangas. Adjacent, a row of large, rust-encrusted dhows sit tethered to the muddy, rubbish-strewn shore.

Abu Baneen Al-Miaahi (43) surveys his morning’s catch. Small blue crabs fill the boat’s hold; silver fish with gulping mouths fill several coloured plastic laundry baskets on the deck.

“Now there are so few fish, a lot fewer than before,” he sighs. “Because the river has gotten smaller, the water in the river is less and the sea gets buried little by little.”

Grabbing a basket, he hoists it onto his shoulder and, surefooted, negotiates the narrow wooden plank onto the muddy shore.

Al-Faw, once dubbed the Ma’Al-Sabr – the Enduring Waters – is dying.

Twenty-five thousand fishermen used to live here with their families. Now, there are only 7,000, according to Badran Al-Tamimi (73), the head of the fishermen’s union in Al-Faw.

“Before, we had 1,600 large fishing boats and 2,800 small fishing boats, but now there are only 180 large and 750 small fishing boats.”

He gestures at the boats lining the shore.

“When I was younger, fishermen used to live a very good life,” he says sadly, shaking his head. “But those who have left fishing are not doing well either. They are cleaning streets.”

Siba

Once upon a time, not so long ago, people would chuckle and boast that Iraq had more date palm trees than people – indeed, so many trees and farms, it was said the country looked “black”.

Siba, about 65km south of Basra, accounted for a good deal of the description. Renowned for the fertility of its alluvial soil, its abundant water and its natural resources (oil), it was once a thriving, comfortable community.

Haha Khadra (30) on her farm, Imami Zamen. One of the last remaining inhabitants of the village, she concedes sadly that they will have to leave soon, that their life on the farm cannot be sustained. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

So richly endowed was Siba that it rebounded from the devastation of the Iran-Iraq War, which was fought in the area. But that was then, when, before the war, Iraq had 30 million date trees – 13 million more than today. That was before the level of the Shatt Al-Arab river plunged, seawater turned it saline, temperatures rose to an unbearable 50°C in summer and the winter rainfall ceased its once-reliable pattern.

Today, the bleak, deserted, sunbaked landscape challenges you to believe it was ever not thus.

Abdullah (32) climbs out of his skiff and ties it to the bank of the canal leading to the Shatt Al-Arab river. He carries a cooler with a dozen small fish lying in brown water and puts it down in the shade by the house on his father’s farm; land which had been in the family for generations, passed down from fathers to sons.

The family’s farm is one of the few still being worked in Siba. Ironically, the fact that there are so few farms left here works to the family’s advantage, enabling them to sell at a local market with little competition. Even so, it is nothing like before, when they lived comfortably off the farm’s revenue. Now, they struggle to make ends meet.

“The problems really started between 2009-12, when the droughts began and the salt water started rolling in,” Abdullah explains. ”Before then, we used to even be able to drink the river water. Now we have to buy it.”

A family of ducks waddles across the dirt path by the house – a toddler, shuffling in two different coloured adult-sized plastic flip flops, close on its heels.

“And the river level has really gone down in the past five years,” he continues angrily, “Iran and Turkey are closing down on us and not giving us water.”

Abdullah’s father, Abu Jalar, has joined us.

“And the heat now is just too much,” he adds. “It goes to 60°C in the summer. Before, it wasn’t anything like that. There is no rain. Last year it rained twice. When I was young, it used to rain all winter, day after day.”

Abu Jamal checking for new growth on his farm. Once renowned as a fertile rural area, where farmers made good livings on their crops, Siba is now nearly deserted , as its farmers find themselves unable to eke out a living as water becomes scarce, rainfall rare and temperatures rise due to climate change. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

The heat has spoiled the famed dates. No longer fit for human consumption, they are fed to the animals. It has killed the fruit trees which used to grow here in abundance – pomegranates, bananas, apricots, figs; they have now swapped to vegetables.

“Heat and saltwater are why nothing is growing here,” Abu Jalar grimaces.

The family is continuing to farm out of desperation: the land and the river are their only resources. “It’s our only chance to make a living. We are forced to do it. But there is no future in it. I can’t force my children to do this,” he says sadly, his voice trailing off.

We turn off a dirt road lined with palm trees, as Abu Jalar takes us to see his crops. A chest-high tangle of vines sprawls under an irrigation system of pipes pierced with tiny holes which drip water onto the plants; opposite, young plants are sprouting from three neat lines of mounded earth, pipes snaking in between. Presiding over all is a large, red water tank.

Abu Jalar bends over to inspect the new growth. Straightening up, he sighs.

“People get depressed and their morale is crushed. My neighbour asks me, why should I farm? For whom? People are getting sick and depressed. Some are having mental breakdowns. Someone in Zubayr even killed themselves.”

Saltwater and snakes

Not far from Abu Jalar’s farm in Siba, Nabil Aboud (44) has called it quits. He had left the farm which had been in his family for generations – “forever” – relocating his wife and two children to a rented house and taking a job as a security guard at the oil facility. He comes here sometimes, unable to let it go.

Rising temperatures and infrequent rainfall – drought punctuated with an occasional flood that drowned plants – had turned the environment into an adversary. However, it was the snakes coming into the house – venomous snakes with triangular-shaped heads – that finally forced his hand. After two attacked him in the house, he realised they couldn’t stay there. After all, two people had already been killed by snakes in their homes in Siba: 55-year-old Talib Bedran and 60-something Matra Muhamed. Matra had been moving bricks when the snake bit her on the finger. Her attempt to remove the toxin failed and she died in hospital.

The vegetable and fruit market run by Media (36). Most of the stock comes from Iran. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

Driven by thirst, the snakes had begun appearing in 2012 when the water in the river started to get salinated. Their appearances have since become both more frequent and more aggressive. With so many places now deserted and so little water about, they are everywhere.

“The water problem destroyed everything,” Nabil says. “Saltwater and snakes made us finally leave.”

“We used to drink water from the river, but since the dam in Iran we can’t do that anymore. Instead of flowing into the Shatt Al-Arab, as it used to, the water now flows back to Iran. It makes a huge difference.

“The Karun used to push away the salts and now nothing does,” he explains. “And then Turkey closed the water with the Ilısu dam two years ago. Due to what Turkey did, it got even worse and finally we couldn’t take it anymore.”

“Our lands and our farms got ruined because of Turkey and Iran,” Nabil stresses.

A pot of plastic flowers hangs on the wall in the deserted house. A drawing of a Qur’an over a doorway. A curtain with a cheerful, idyllic palm-fringed beach scene. Clues to the lives once happily lived here. Out back, palm trees, many just dead stumps, mimic the refinery chimneys with their flickering flames beyond.

This is where Nabil’s father was born and died. When his own sons were born, Nabil dreamed of the day they would inherit it and pass it on to their sons. That was when it was so beautiful here that people came from all around to ask permission to picnic on their land.

Water markers inserted high up on the rocky shore show just how low the water has dropped in the Sirwan River. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

Now, he is no longer his own boss, working freely and being free on his own land. It is a change he has found devastating. “It really upsets me. I just want to give up.”

Surveying his land, with its stunted trees, he sighs.

“I am very hurt. You see your palm trees dying and your land is dying. It’s the end of the line for our family. It’s ended.”

Basra

Across Iraq, temperatures have risen by at least 0.7°C over the past 100 years.

Thirty years ago, explains Professor Shukri Al Hassen, an environmental expert at the University of Iraq, temperatures would reach 50°C on one or two summer days. Now, the temperature stays there for weeks on end.

Drought was also previously an infrequent event. But since the 1990s and early 2000s, drought waves have doubled six times, he explains. Rainfall used to average 160mm a year. Now it is only 60mm to 70mm. The 2020-21 rainy season was the second-driest in 40 years.

“Two districts, one town and several other large areas have been removed from the classification of agricultural land. Thirty-five fish farms have closed. Now, only 7% are operating and the other 93% closed because of a lack of water. Farmers have left their farms and animals,” says Hadi Hussein Quasi (53), Basra’s manager of agriculture, sitting at his desk in his office, behind four neat piles of documents, an Iraqi flag on the wall behind him.

“These areas were full of orchards and gardens and farms – and they are now all out of commission,” he acknowledges, destroyed by extreme heat, water scarcity and the salinity of both water and soil.

He estimates that the farm closures have cost the agricultural sector of the economy 30%, while those who have been forced to abandon farms have seen their standard of living plummet.

In October 2021, Iraq’s president Salih emphasised the gravity of the long-term threat of climate change to the county, noting: “Desertification affects 39% of Iraq’s territory and increased salinisation threatens agriculture on 54% of our land.”

Sewerage, hospital water and water contaminated with the chemicals used to clean bodies in nearby Najaf pours into the Euphrates River here. The lowered level of the river increases the concentration of pollution – a fact which is attributed to the spike in cancer cases in the area. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

According to the World Bank, it will only get worse, with temperatures in Iraq expected to rise by 2°C by 2050, and rainfall to decrease 9%.

The oil industry, ubiquitous in this part of Iraq, uses five million barrels of water per day and further exacerbates the crisis, as do the dams: the Ilısu in Turkey and the Karun River diversion in Iran.

“The dams are one of the prime reasons for the water problems in Iraq,” Professor Shukri says.

“We live in a catastrophe due to the dams in both countries,” he continues emphatically. ‘All these elements” — climate, oil installations and the dams – “unite to create an environmental crisis.”

The consequences cascade: less water in the river concentrates pollution and salt. According to Abu Abdullah Haider Sami, 39, the station operator of a water purification plant on the Shatt Al-Arab river in Basra, 118,000 people who were hospitalised in 2018 had been poisoned by water that had actually been purified.

He explained that, at the time, they had been using standard river water filters, switching them out every month due to the extreme levels of salt and waste they had to deal with. Clearly, it wasn’t enough.

“They were useless,” he shrugs. After the poisoning, they switched to using heavy-duty sea filters. But as the water quality continued to deteriorate and the level of salt continued to increase, they installed a second set of sea filters. Now the water is run through both sets of filters, thoroughly purifying it twice.

The doubled time and equipment have added to the cost.

“Right now, salt levels reach such insane levels that a tonne of purified water, which used to cost $1.50 when salt levels were 1,000ppm or below, now with salt levels of 15,000ppm, costs $25 a tonne, due to the extra purification,” says Anwer Nathar (50), a geologist and owner of the purification facility.

In the summer of 2019, he explains, the level went up to an even more staggering 18,500ppm, pointing at the salt heavily encrusting the valves where the water circulates through the purification process.

“The long-term solution is obvious. We open the water coming from Turkey and Iran.”

Iraq should be able to force Turkey and Iran into releasing enough water, he says: the problem is political. “Iraq is strong – but,” he snorts derisively, “it’s like it took anaesthesia. Like Mike Tyson is drugged and is fighting a rookie and the rookie will win.”

Ghalib Ammon (50) has lived here his whole life, as have generations of his family, but lack of water is making it impossible to stay. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

If not resolved, the water scarcity and climate change will cause local military conflict in the south of Iraq, he warns. “Wars about water have already started. The West is fighting Iraq over oil. Iraq is fighting for its survival.”

Nahran Omar

The road heading north out of Basra closely parallels the Shatt Al-Arab river. The river once fed the lush farms and palm trees that stretched to the horizon here, but today it is a vast, monochromatic wasteland, punctuated only by the flame-belching smokestacks of oil refineries.

Extreme proximity to the smokestacks of the neighbouring oil business has caused diseases in the area to escalate. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

Fifty kilometres north of Basra, the village of Nahran Omar nestles at the nexus of the triad of elements comprising Iraq’s environmental crisis – climate, oil installations and the dams.

As the sustained droughts and sweltering temperatures of climate change and the dams in Turkey and Iran crippled the farms which had previously thrived, oil installations, bearing down at a proximity which has cast the area in a permanent flickering golden light, have added to the problems, spewing toxins into the air, killing crops and causing rates of disease to skyrocket. In 2003, there was only one flare. Now there are more than five. The increase in diseases has grown in tandem with the oil installations.

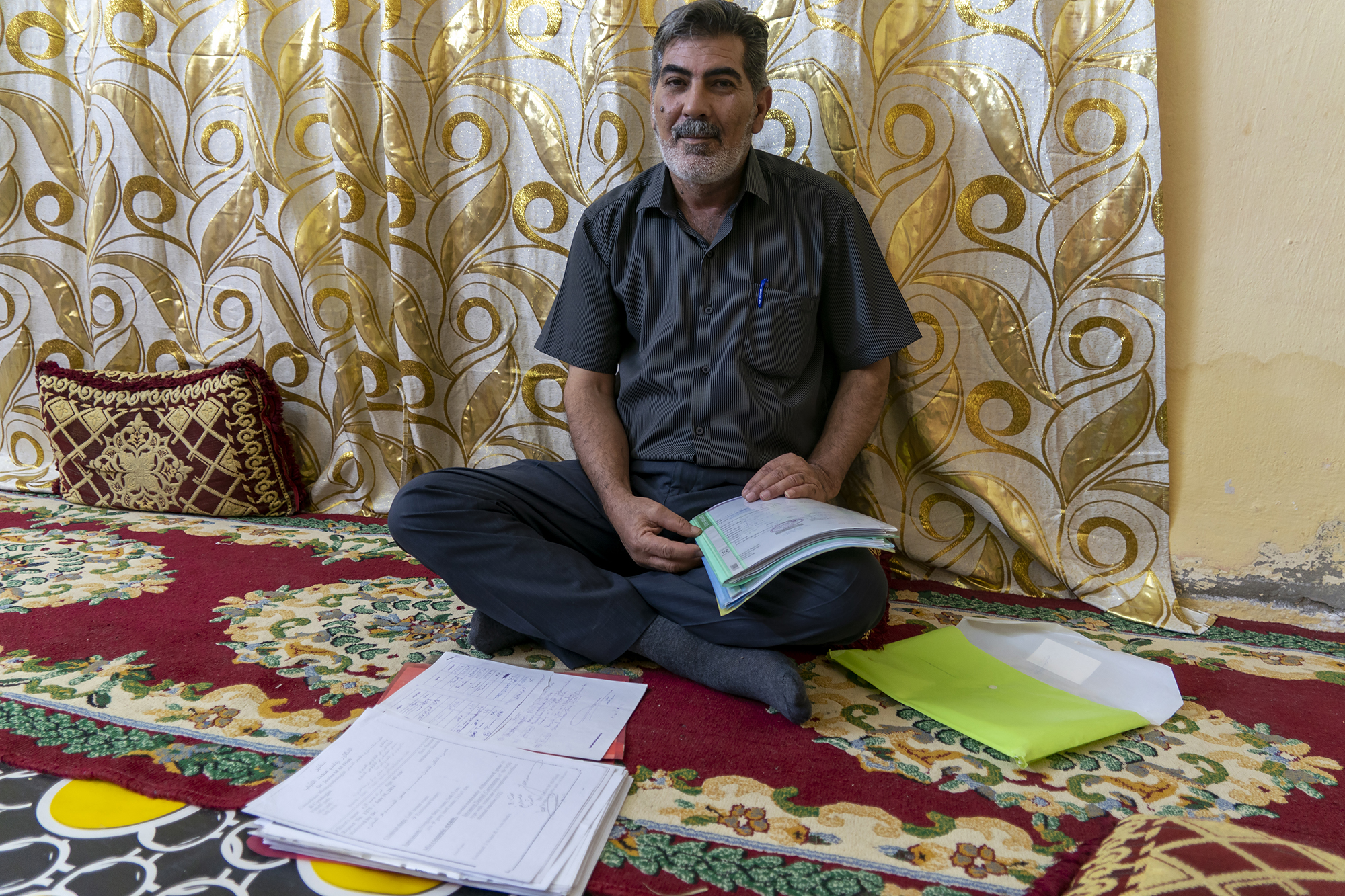

Mayor Bashir Al Jabiry (55) sits cross-legged on the red patterned carpet in the living room of the house he has lived in for two decades. He spreads out a 7cm-thick sheaf of medical reports and documentation detailing the rise of diseases in the area on the rug in front of him, loosely organising them into piles.

“These are medical reports of different kinds of cancers and skin diseases,” he says. “These are medical reports for people who have died through cancerous diseases and who are cancer patients here now.

“And these,” he says sadly, pointing to another stack, “are reports of the deceased.”

The smokestacks of the oil refineries hover in the background as the population of the marshes becomes increasingly impoverished because the water is disappearing. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

By Jabiry’s accounting, 54 residents have died of cancer in the past six years, while 33 are currently ill with cancer. In this village of 1,500, that amounts to roughly 6% of the population.

“In this small area of around 150 houses,” he adds, “one-third have diseases – diseases of various kinds. Right now, there are more than 100 cases and around 40 are severe.”

Nearby, Saddiq Tahar (51) is surveying his small date grove as the sun sets. The trees flicker gold as the flares of the refinery smokestacks hovering just beyond his garden wall cast ghostlike shadows.

Saddiq no longer cultivates most of his land, nor raises any livestock – this grove is all that is left, the rest lost to the ravages of pollution, the heat of the flares, water scarcity and climate change. There is too much salt in the water for the dates to survive, he explains, and, pointing to grey specks on the fronds, the oil drops kill the dates. His income has dropped to a fraction of what it was.

Worst of all, however, was the loss of his son, Jaffa, who died from leukaemia when he was only 16, a junior in high school with a promising life ahead of him.

The mayor has filed innumerable complaints and compiled countless health and environmental reports attesting to the toxicity of the environment, agitating for change and compensation. He had a small victory when 90 people, chosen, he explains, “at random”, were given 500,000 dinars “as assistance, not compensation, by the South Oil Company, an Iraqi company based in Basra”.

“Assistance, not compensation,” he emphasises. “Compensation would be a concession of guilt.”

Half a million dinars would not even cover a doctor’s appointment, he points out.

But nothing has been done to compensate for the decimation of the once-vibrant community.

“Of course, it makes me angry. Everyone here is angry.”

“Farming is almost eliminated. The emissions from the oil fields rain oil drops on people and on crops, killing the crops. It is like it is raining, but with oil, when the emissions get very thick,” he says, his voice thick with emotion. “Some days, because the emissions are so thick, you feel as if there is no oxygen.”

“Life here has almost disappeared.”

Al-Hawizeh Marshes

The contrails of belching smokestacks follow us as we travel north, a dirty smudge hanging low in the blue sky.

Beyond Al-Qurnah, we turn off and head east towards the Iranian border and the Al-Hawizeh marshes which straddle the Iraq and Iranian borders. We pass a small factory where people shape the bone-dry and umber-coloured earth into bricks, and an occasional mud home whose primitive construction contrasts with the omnipresent flaring smokestacks of the oil refineries in the distance. Now and then, we pass through a small, deserted and dusty village, plastered with pictures of martyrs.

Mayor Al-Jabiry lays out the records of those afflicted with cancer in Bahrain Omar due to the toxic emissions spewing from the oil refinery smokestacks. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

This once-fertile land was a cradle of civilisation in ancient Mesopotamia. The Marsh Arabs have lived here since that time, fishing and raising water buffalo.

Myths and mystery abound about the Al-Hawizeh marshes. Salomon’s treasure is believed to be buried here, protected by a “djinn” – an invisible spirit inhabiting the Earth – in the Tel-e-Fil, a hill where lights are said to inexplicably appear at night, and where venturing too close apparently makes a person dizzy.

But now, both the land and its ancient peoples are under threat of disappearing.

Over the past eight years, the water level has dropped dramatically from 2m to a mere 17cm in some places, explains economics professor Ahmed Saleh Na’ma (50). He points to where narrow, low marsh boats sit beached on a tangle of mud-encrusted reeds on the dry, cracked shore – fully 200m from the water’s edge. We watch as a boat disappears behind a curtain of reeds in the distance.

Only a few years ago, he explains, the water came up not just to where the boats lie beached, but a full 100m further up the gently sloping shore.

Ghalib Ammon (50) has lived here his whole life, fishing and raising water buffalo, just as his family has done for centuries. He survived the Iran-Iraq War, Saddam Hussain’s draining of the swamp, and being shot by the Islamic State as he fought with the Hashd Al Sha’abi militia. But he doesn’t see how he can survive here anymore. There’s no water.

“I am about to leave, along with everyone else,” he says sadly. Adjusting the black-and-white patterned keffiyeh wrapped around his head, he turns and gestures at the pools of water below, set within a reed-rimmed dry expanse of land. A handful of water buffalo are lazily making their way across. The water used to come up to where we are standing, he explains. Now it is 4m below.

“Every summer is hotter than the one before and there is not nearly as much rain as before,” he says, pausing to watch as a pick-up truck filled with reeds passes by, a young girl dressed in a full abayah sitting atop.

The Ilısu dam, Ghalib says, has made the water scarcity unsurvivable. Not since Saddam drained the marshes has it been dried out as it is now.

“The lack of water is destroying agriculture, fishing – and when the water buffalo have water, they produce 30 litres of milk. Without water, it’s only 10. It’s not just me… everyone is leaving for the same reason.”

He sighs. “If this year doesn’t get any more rain, I doubt anyone will be here next year.” His voice trails off.

Najaf

North of Nassiriya, the clumps and patches of green become more numerous, interspersed between areas of pure desert, tawnier in tone than further south, where it has an unattractive grey cast. A Bedouin leads a herd of skinny camels. They have walked all the way from Basra, where they normally live, in a search for water, I am told.

Natural small depressions in the sand with remnants of water are encircled by wide ribbons of dried salt. A shallow, narrow canyon briefly splits the desert to the east, parallel to the road. The striated layers of earth seem to betray a distant past when water coursed through.

The Hafar river, a tributary of the Euphrates, branches off the road to the east as we approach Diwaniyah. Crossing the Shatt Al-Shami, another tributary of the Euphrates, fields of wheat spread out to the east.

“Iraq has a lot of water,” the driver remarks dryly. “Only Iraq doesn’t get to benefit from it.”

Those displaced, forced to leave their farms, come to cities like Najaf, leaving behind everything they have ever known and land that has been in families for centuries, to settle in urban areas – usually squatting on the fringes – where, after lifetimes of working for themselves, they must find jobs, working for others. It is a huge rupture, an incalculable loss of income, culture and morale for which they are ill equipped.

“Now we see that agricultural land is getting less and less due to low levels of water reaching farmers because of climate change and the decrease in water releases from Turkey,” explains Adam Hamid Nassar, Najaf’s manager of the environment.

“The whole direction is against farming. It has led to the migration of peasants to the cities.”

This translates to more population, more needs and more problems, he observes. The infrastructure is stressed; the electricity supply can’t cope with the extra demand. Schools, built to accommodate smaller student bodies, lack the capacity for the numbers of additional children arriving, displaced from farms by climate change. Children end up sitting on floors; teachers are forced to deal with unwieldy class sizes that degrade the quality of education, angering parents.

Migrants, who often end up working low-paid jobs in cemeteries or “hammams” (public baths), are blamed for crime, accused of stealing electricity and water, and the areas where they live are seen as havens for gangs. There are frequent complaints from nearby neighbourhoods. Tensions are at boiling point.

“An underclass is growing from those leaving farms due to environmental problems,” Nassar warns.

It is only going to get worse.

Iraq is losing roughly a staggering 250km2 of arable land – or 100,000 Iraqi donums – to desertification every year, according to a June 2021 report by Iraq’s Parliamentary Committee for Agriculture, Water and Marshland. Inevitably, this will create ever more environmental migrants and instability. In October 2021, Iraq’s agriculture ministry announced that the crop planting area for 2021-22 would be reduced by 50% due to water shortage.

Read in Daily Maverick: “On the fence about climate change? We check the facts with three experts”

“We are between great drought and total collapse and are mostly reliant on rainwater. If there is no rain, there is no agriculture,” says Haider Muhammed Saleh (51), the chief engineer of urban environment for Najaf. He doesn’t mince his words: “Soon Iraq will hit the phase we call the ‘Juhid Al Mai’,” he says bluntly.

The “Juhid Al Mai” (literally “water efforts”) is the catastrophic point at which Iraq will run out of useful water; the tipping point, where the little remaining water becomes toxic, contaminated by the waste and sewage disposed of in rivers and by skyrocketing salinity: the lower the water, the higher the contamination.

Nail Aboud at his abandoned farm. Water scarcity and snakes forced him to abandon the farm which had been in his family for generations. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

“We expect the Juhid Al Mai to come in 2025,” he says, pausing to allow the impact of his words to settle. “2025.”

Turkey’s dams and hydroelectric facilities on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers were already estimated to have reduced water in Iraq by 80% since 1975 – even before the Ilısu dam, which sits on the Tigris River in southern Turkey about 65km above the Iraqi border, was filled in 2019.

The dam has reduced the water level of the Tigris River in Iraq from its pre-Ilısu flow of roughly 600 cubic metres per second to about 300-320m/second, according to Ramadan Hamza, a senior expert on water strategy and policy at the University of Dohuk.

It is nothing short of catastrophic, dramatically compounding the impact of climate change. Even the 300-320m/second is not a sure thing: the tap is controlled by Turkey.

Releasing 500 cubic metres per second, as Iraq has asked, would make the difference between survival and disaster. ”If they gave us 500cu/sec, it is not enough, but,” Saleh acknowledges, “it would be enough to survive”.

But Turkey isn’t releasing that amount, and with 22 more dams planned on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers as part of Turkey’s ambitious Southeastern Anatolia Dam Project, the problem is only going to get worse.

“A water war is expected,” he warns. “Our fate seems to be drought. It is a disaster and that is the situation now.

“Iraq might not be capable of waging war against Turkey – Turkey has more power and alliances – but if Iraq had a wise government, they could use the oil file to apply pressure – to create economic pressure on Turkey. When you have diplomatic problems, war is the last resort.”

Newly elected parliamentarian Hadi Hassan al-Salami, who ran as an independent in Iraq’s 2021 elections, is angry.

“The national development plan 2018-21 and ministry reports all speak of the water pollution, the destruction of the environment and the infrastructure of the public services, including water services,” he thunders. “And they all remain ink on paper!

“International agreements reached on water issues with Turkey and Syria! They are also just ink on paper – all of them, all ink on paper, nothing more!”

He is determined that the new parliament, with the unprecedented winning numbers of independent candidates, will have the mettle to tackle the situation.

“We as winning parliament candidates will go to Turkey and Iran and Syria and demand they comply with international agreement, and if they don’t, we have measures. These countries all benefit from Iraq and we have measures to take in order to serve the interests of the people who elected us.”

He leaves unspecified what the measures might be. Instead, he underscores the importance of resolving the situation with a line from a Qur’anic verse.

“We made from water every living thing,” he intones gently.

Kufa

The river is wide, idyllic, the far side thick with palm trees. Eleven-year-old Muktada Abbas Fadey cycles over to the riverside and dismounts, dropping his bike to the ground on the top of the steep bank where a tangle of reeds descends to the water roughly 4m below.

“Pe-ew,” Muktada says, wrinkling his nose at the foul smell coming from the river, the Shatt Al-Kufa, a tributary of the Euphrates.

“And it is even worse at night,” he says, pointing to the two pipes coming from under the road, which are spilling thick, green, opaque water into the river – water contaminated with all manner of untreated waste from Kufa and nearby Najaf. All the waste from the area’s hospitals enters the river here, as does the chemical-laden water used to wash the millions of bodies put to rest in the world’s largest cemetery in Najaf.

Read in Daily Maverick: “20Twenties: Eve of Destruction – Daily Maverick featuring Anneli Kamfer”

The consequences of such heavy contamination are evident: in crops, thousands of donums of land can’t be planted because of pollution; in animals, who, when slaughtered, are found to have tumours that render the meat inedible; and in humans.

Cancer in the area is rife and has been on an upward trend over the past 10 years, according to Dr Haider el Shibli, manager of the tumour centre in Najaf.

The trend, he notes, has kept pace with the escalation of environmental degradation. Ahmed Hussein Al Ghali (45), ambassador of childhood diseases, has observed the same pattern, witnessing an increase in cancers attributed to environmental causes, something Abu Zain Al Abueen Hassan Hakim (40) has experienced first-hand.

He has thyroid cancer. His mother has brain cancer. His sister has bowel cancer. “Now in Kufa there isn’t a house that doesn’t have cancer in it,” he sighs.

When Abu Zain Al Abueen Hassan Hakim became ill six years ago, the environmental problem he had long been aware of became personal. He stopped making videos about public services and became an activist, putting all his efforts into exposing corruption and demanding sewer and water projects – thus far, in vain.

It is a dangerous business.

“I am sitting with a pistol beside me to protect me,” he admits, sitting in his voluminous living room in Kufa, its windows double-hung with two layers of heavy drapes, colour coordinated to the couches encircling the room.

“You expose corruption to save people’s lives. It’s a humanitarian thing to do. But you are endangering your own lives. We know this road of activism ends in death,” he says, reeling off the names of activists who have been assassinated recently.

As we walk through the majestic remains of the ancient city of Babylon, Dr Ahmed Aziz Salman points out that the problem with water is not new. However, he notes, environmental changes which evolved over millennia for the Sumerians, have today taken fewer than 40 years – and the pace is accelerating.

A small island newly formed in the middle of the depleted Tigris River in the centre of Baghdad is a sobering reminder.

Sulaymaniyah

Eight hundred kilometres north of Basra – 265km north of Baghdad as the bird flies – the bald ochre hills of Iraq’s Kurdistan roll gently east from Sulaymaniyah, an occasional deserted farmhouse or green speck of a tree punctuating the monochrome. The hills tighten and close in as the road climbs, until we arrive at the Iraq side of the Iranian border. Below, nestled in between steep cliffs, the Sirwan river carves a narrow path as it travels from Iran into Iraq.

Mossin Aziz (49) and Atatam Hamarashi (42) man the lonely border post. Mossin points at the striations on the sides of the cliffs below, where the water level honed over centuries is scribed, but today the water is far below.

At the base of the hill where the river bed opens on the Iraq side, instead of spilling into the rocky bottomed, widened river bed, as it should, the water flows shallowly in a narrow path, leaving water level markers inserted among stones smoothed over centuries by a rushing river many metres from the water’s edge.

Mossim is a farmer from a village near Darbyhan. He had only taken a job at the border post when he could no longer support his family through farming. First, he explains, when droughts started becoming more frequent and prolonged, he adapted by changing crops, reducing his livestock and tightening his belt. But when Iran opened the Daryan Dam on the Sirwan river and cut the water downstream into Iraq, it was the final blow: there was no longer enough water to survive.

Local fishermen find they no longer can make a living and are forced to move into work which is usually the least desirable – such as cleaning streets. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

Their loss has been Iran’s gain. It is cheaper now to buy agricultural products from Iran than it is to produce them.

It is decimating the area – 50% of agricultural land has been lost.

There are 300 houses in Mossin’s village. Now, all but a handful are empty.

“Water is a life source,” Mossin says sadly. “When they cut the water, they cut our life.”

Halabja

“Tomatoes, cucumber, beans, figs and okra… that’s all that we sell now that comes from Iraq,” Media (36) says as she fills a bag of pomegranates for customer Backtair Horramy at her Halabja fruit and vegetable shop.

“The rest we get from Iran. And if the drought continues like this, we will lose everything – all the farms.”

Read in Daily Maverick: “Climate change threatens the livelihoods of all of humanity, especially those in the Global South”

Horramy grew up in Halabja. He survived the 1998 chemical attack but he couldn’t survive the water scarcity. After the Daryan dam was built, he could no longer make ends meet. Reluctantly, he abandoned his farm and relocated to Sulaymaniyah, a city of 750,000 about 80km northwest of here.

But he can’t quite let go of a place which is in his blood. He has come today, as he does periodically, for the memories.

Near Halabja

A dozen troughs sit on the side of a dry field, a pipe snaking from them down through a gulley and into thick green water which sits at the bottom of a deep hole. This was once a fertile area, where anything would grow and where tobacco and rice were popular, lucrative crops. Now, those who are still trying to eke out a living from their farms, have switched to wheat and barley, crops which require less water. Livestock and acreage have been sold to make ends meet.

“The water in this well used to be 6m high – it used to come nearly to the road,” Kewan Akram (28) says, scowling in frustration as he adjusts the pipe, trying to coax some water out of the hole and into the troughs. “But since Iran finished the dam, it is nearly completely dry.”

Sarkwat Rashid (39) Kewan’s colleague, is looking on in despair, as if willing the water to reach the troughs.

Kewan is from nearby Zardahall village, where, he explains, there is no water at all anymore: “The river was a source of water but slowly, slowly there was climate change, and then Iran started stealing the water. We have been destroyed,” he fumes. “We lost our animals, we lost our farm – all because of the water shortage. We are devastated.”

The loss of the ancestral farm sent Kewan’s father spiralling into a deep depression, from which he has not recovered. Kewan now works as a day labourer.

“One more year of drought, it will be desert here,” Sarkwat explodes. “The Iranian government suck your blood – but our government is worse, taxing us a lot but providing no services!”

Imami Zamen

Upturned boats sit on lizard-like scales of dried mud which stretch 500m to a narrow strand of the Sirwan river – the river relied on in these parts and curtailed by Iran’s Daryan dam. Nabil Musa is a Kurdish environmental activist who has been coming here for years. He is stunned. He’s never seen the water this low before.

The nearby town of Imami Zaman depends on the Sirwan river for water but when it is low, the water in wells dries up and, with a prolonged drought, there is no hope even of rainwater.

The water scarcity has driven most of the 70 families in the village to leave. Immigration is on the minds of everyone else.

A basket of Barbie dolls sits in a corner of an empty house, a crumpled old photo of seven young boys is tacked to the wall: signs of the Laten family’s once happy lives before their departure a month earlier. Safi Laten (22) has come back now to check on the house.

“There is no way to survive here anymore,” he shrugs. Immigration is the answer, he says.

Smugglers come through frequently. The previous day, 57 people had left for Belarus from a nearby village.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Azad Khalid Muhammed (62) and wife Famia (51) have parked their SUV and are surveying the parched fields extending to the horizon. Azad – a supervisor of language teaching before the school closed – and Famia raised 13 children here. Nine of their children have already gone abroad and now they are contemplating sending the remaining four.

“The water here has disappeared now,” Azad explains, “There’s none anymore. None for animals, vegetable farms, fruits or fishing. We lost all of them. That is why everyone is migrating.”

The smuggler has told Azad and Famia that for $3,500 each, he could put them on a plane bound for Minsk within a few days.

“It’s like a flood of people. Only the poor people and very, very rich stay behind,” Famia says sorrowfully. “We’ve lost our culture and our morale. It’s displacing everyone.”

Read in Daily Maverick: “Climate change compensation fight brews ahead of COP27 summit”

Hazha Khadra (30) is one of the village’s few remaining residents. She fills a trough with water from a hose for her cows as her small daughter runs behind giggling. With no water from the river and with drought killing crops for fodder, what they spend on water and animal feed is more than they can earn.

“We cannot continue like this,” she sighs. “We will have to leave too.”

She stares out over the hills.

“This land has been in my husband’s family for years.” She falls briefly silent. “He will be devastated to leave, but we don’t have a choice.”

“But if Iran opened the dam, we could stay. All the water would return and the wetlands would come back to life. We are furious that Iran controls our lives with the tap. And we have no power to change it.”

Darbandikhan Dam

The Sirwan river runs on the border between Iraq and Iran, before it turns decisively into Iraq, spilling into the picturesque Darbandikhan Lake which, at its southern tip, brings water to the Darbandikhan Dam.

The dam was built between 1956 and 1961 to supply hydroelectric power, irrigation and flood control to the region. Today, however, the water level is catastrophically low, a level unprecedented in its 65-year history, and its capacity to function is crippled.

For the first time since it was built, the roof line of the factory gravel mine used when constructing the dam sticks out above the water level, and a bone-dry rocky bottom leads into a spillway, far below the level of the hatches through which it needs to flow.

Arkan Muhammed (57) has been working as a driver and security guard at the dam for 18 years. “We were okay until Iran completed the dam three years ago. They have really destroyed us. They can release the water but they don’t.”

The water is 9m lower than last year and it is dropping 8cm a day, he explains.

“Water is a natural resource – a natural human right – of course I am angry with Iran. Between drought and Iran, if we continue like this we will really be in trouble. We need to pray for rain, and for Iran to release the water.”

The huge windows in his office overlook the dam; a screen on the wall displays a grid of images from the dam’s cameras. There is no water coursing through the dam right now. Water markers run up a dry wall; the water many metres below.

Ali Abu Kareem (53) stands outside the yellow building housing the dam operations at the base of the dam. A project manager and the machine operator, he explains that the problem with the dam in Iran is that they have built tunnels and canals which divert the water back into Iran, to their agriculture, instead of allowing it to run into Iraq as it should.

“They are choking us. Seventy percent of our water comes from Iran.”

At this level, the dam cannot generate the electricity it should, he explains. Water should run through 24 hours a day, enabling, as designed, the dam’s three turbines to produce 250 megawatts of power each. Now, however, they can release only six hours’ worth of water in 24 hours, producing a mere 50MW. It is not nearly enough to supply power for Erbil, Kurdistan’s capital, as is intended.

“Electricity supply has been reduced by 80%,” Kareem says, pointing out that electricity for Erbil now depends on coordinating supply with other dams. “We don’t even release it now for the electricity. We release it because we don’t want the people downstream to suffer.”

Read in Daily Maverick: “From smart agriculture to 3D-printed houses, 4IR tech can help combat the climate crisis”

It can get worse. If the water drops a further 4m, there won’t even be enough pressure to release the water at all, choking everyone downstream and compromising electricity in Kurdistan’s capital.

“But forget about Iran! Of course what Iran does is dangerous – but the biggest danger is climate change and global warming,” he says.

“Have a look. You can see the trees. We have a wildfire here every year. Greenery is disappearing. This year we had hardly any rain – there is less and less rain and it’s hotter. This year with the drought we had high temperatures. I am praying for rain.”

He pauses and looks at the surrounding brown hills.

“Water is life. When you don’t have water, people will go. You don’t have life. Even birds will migrate.”

It used to be so different. “When I was little, it was paradise,” he says. “It is just heartbreaking.”

Banihelan Village

A narrow strand of the Sirwan River snakes below the eroded river banks, a slash of blue amid hills which undulate in tones of umber until they erupt into distant mountains. An occasional eagle soars above the parched and deserted landscape, until, as we turn the corner, a bright-green field spreads out on the side of the road. Roughly a dozen men are bent over picking the crop.

Farhan Hussein (52) pauses to talk, a bundle of upland rice stalks in his arms. This is his farm but, he explains, it is a shadow of what it was. “Now we get only two and a half tonnes of rice. Back in the day, we would get 100 tonnes.”

Lack of water in the Shatt al-Arab River allows salt water penetration into the waterway, affecting fish in the river, and lack of freshwater entering the Gulf threatens the ecosystem of the entire Gulf. (Photo: Susan Schulman)

He looks out over the fields, where the men are hard at work. “It’s not enough. We are just not going to be able to continue to live on the rice,” he says, shaking his head. Turning away, he gets back to work.

Lalihan Village

Turning off the main road, we bump over a rough, stony road heading in the direction of the river and Lalihan village. There is a certain otherworldly beauty here as layers of stones merge into layers of sand, progressively rose-hued as they rise into hills beneath a bright-blue sky.

It is impossible to see how anything could ever have thrived here on such stony, arid land – but it did. There was grass enough to feed the livestock and water enough for animals, crops and the local population alike. Farmers lived a good life.

A tangle of green vines pokes out over the cinderblock wall surrounding the compound where Jalad Rostum (53) lives with his wife, Fatima Hamma Said, and their three adult children. A huge man with hands like shovels, a bushy moustache and deeply creased laugh-lines, Jalad invites us in. A thicket of vibrant orange flowers blooms under the wall, in colourful contrast to the monochrome of the hills beyond.

In the 1990s, Jalad began to observe climatic changes. Rainfall lessened, droughts started becoming more common and the temperatures increased. “That is when the crisis slowly began,” he explains.

But when Iran built the Daryan Dam in 2009, things took a drastic turn for the worse. With the water on the river reduced, dependency increased on rainfall, which continued to diminish, and drought became the norm.

“We had to stop growing everything. Nothing grows anymore. No rain. No water. It’s impossible,” Jalad says.

Farmers are losing money right and left. With no grass, they have to buy food for cows. With no water, they can’t feed them properly, diminishing their worth in the marketplace. It is a losing proposition and one that is happening fast. Five years ago, Jalad had seven cows. Now he only has two.

He has lost $5,000. Some here have lost $100,000.

It is unsustainable.

“We can’t stay here. We will be next to die,” he says. “When water dies, we will be next. One more drought, one more year of drought, and we are facing death.”

Fatima’s face has crumpled. She is on the verge of tears.

“It’s the most devastating thing. We have been born here and if we have to leave, we are going to die.” DM/OBP

Requests to visit Turkey’s Ilısu Dam and environs were denied. Relevant ministerial departments refused to answer questions despite multiple requests.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.