GASTROTURF

Parks and recreation at fine old tables of the Cape

The Cape restaurant scene exploded in the early Nineties and suddenly ‘foodies’ were everywhere. In the culinary madness, new restaurants came and they went, the doors opened and they closed. Flavour of the Month was never more fitting.

The breath of fresh air that blew through South Africa in the early to mid-Nineties was accompanied by a revolution in the Cape restaurant industry. Eateries sprung up seemingly every week. People who formerly had been merely people were now calling themselves foodies. I found myself as editor of Top of the Times, a weekly high-end supplement in The Cape Times, and we soon became the go-to portal for what was happening on the city’s burgeoning food scene.

Before this seismic shift in the Cape restaurant milieu, things were very different. You’d go to the Van Donck Room in the Heerengracht Hotel for a fine repast in the classic tradition. To Hildebrand in St George’s Street. To La Perla (yes, it seems always to have been there, just as Nelson’s Eye never fades). To Kaapse Tafel for a lovely old Cape selection of traditional favourites. The Townhouse or Europa for reliable fare. Mario’s in Green Point for Italian. Maharajah for Indian. The Mount Nelson Grill room for a splashy night out with dinner and dancing and trolley service at the table. The Hussar Grill in Rondebosch, and Barristers in Newlands for a taste of England. Jonkershuis and a slew of winelands places where a Ploughman’s Platter was the order of the day in the leafy sunlight with a whiff of grape must in the air. Many more, but nothing like the sheer numbers of restaurants that entered the fray in the Nineties.

A fresh breeze blew in to change everything forever. It felt as if that breeze would not blow before social change had happened. Now everyone could be part of it as segregation fell away. Where before had only been Chinese restaurants, suddenly there were a slew of Japanese places, Thai restaurants, Vietnamese, and more generic Asian ones where the menu would take you on a taste tour of various cuisines from the east. Pizzerias abounded, turning into chains that swallowed up main streets. Burgers got posh. Chefs started “stacking” food high on plates in what seemed a great idea until you shoved your fork in somewhere, anywhere, and the gorgeous vision collapsed into a mound of nondescript nosh that might have been sloshed on the plate by a canteen chef.

We’d review a new restaurant, and like lemmings the punters would leave the last one you’d raved about and proceed in single file to the next new place to be and be seen to be. I used to collect restaurant menus. Many excellent eateries closed their doors as the ravening beast snaked from one venue to another, leaving in their wake people who had spent millions or at least many thousands on revamping what often had been a perfectly nice looking interior before they changed everything to suit what they hoped was what diners wanted. As if we can ever know that. We wrote about restaurant closures as often as we wrote about openings. By the end of the decade I owned a pile of mementos of places that had been, some of which I could barely remember. (You’re welcome to remind us of some of the old places in the comments below.)

After a while it began to wear me down as I realised I had allowed myself to be caught up in something I was uncomfortable with. Increasingly, I’d return to those places that just made good food in a pleasant environment, didn’t try to be overly fussy but were relentlessly professional. There were not a lot of them.

Interestingly, one of the most reliable and attention-getting of them all was not chef-driven, but steered by the man (a chef, yes, but who relied on a head chef in the kitchen while he operated as manager and restaurant guru-in-chief) whose name was associated with it, in the way that my perennial favourite Cape restaurant, Societi Bistro in Gardens, is run by owner Peter Weetman and also not chef-driven. Interesting, in light of all attention focusing on the chef in these times. Often we don’t even know who the owners are. If they’re even present. But in the case of Societi, and the restaurant I’m about to talk about, the owner is or was always visible, with a keen eye on every plate that goes out, drawing up the menu in tandem with whoever the chef is at that moment, creating the mood, the atmosphere, choosing the decor, the colours and textures, lighting, the chairs, crockery and glassware, all the aspects that make a restaurant worth going back to. Everything about the place has to do with that person’s wants and expectations of his crew. Once you have all of that, your chef’s job is to make magic on the plate and palate. For me, some of the best restaurants are those that operate like this. The chef is an important part of what happens, but there’s a magician on the premises who knows how things must be if it is to succeed and continue to succeed.

Which is where Michael Olivier enters the story. Michael is the gentleman connoisseur, the gourmand with an unassuming smile that suggests a doffed cap and an agenda to feed you and see to your well-being, with a demeanour of old-world elegance and charm. You can imagine him being at ease in Parisian café society of the Beau Monde era, as a man-about-town in Noel Coward’s London, or as a butler to a pommaded gentleman who has to be protected from his wayward self, like Gielgud to Dudley Moore in Arthur.

Michael Olivier. (Artwork by Roelien Immelman)

He only ever approaches you with warmth, a quality ideal for one who operates front-of-house in a hospitality business, as he has done in various capacities in his life.

When, finally, I met him in June 1993, he must have been on the periphery of my life for years without me knowing it; in the way that Lanzerac and the buffet at Boschendal were somewhere in the wings of my days and years, and in the parallel worlds of shared interests. I liked him and his wife Maddy (Madeleine) instantly, and that warmth has always been reciprocated.

It was through my Top of the Times job that I met him, which until recently had always been my favourite job (this one is, now.) I’d arrived at Parks restaurant in Wynberg on the edge of Constantia, which was about to open. It was just off the Blue Route freeway at the point where Wynberg meets Constantia. It was never close to where we lived in the City Bowl, so we couldn’t get there as often as we’d have liked to, but we knew it well enough for our daughter to consider it one of the places she more or less grew up in.

The place was gorgeous, perfectly placed in an old house, and it looked so inviting, a place where you’d love to dine as long as the food was good. He described the menu and their plans winningly. It felt “right” to me, as if something was about to happen. You develop an instinct for these things, the more you’re exposed to the industry and the way individuals operate.

I didn’t know, then, that Michael had been at Boschendal and that I’d probably seen him flitting around whenever I’d been there for the fabulous old Cape buffet. Maybe he just worked his PR spin on me with great success when I pitched up that day at Parks. But I was impressed, so I wrote a story on what punters would expect from Parks and it was our lead story that Saturday. The phone at Parks started ringing and by the time they opened their doors days later it was becoming difficult to secure a booking for weeks ahead. It carried on like that for what I believe was 10 years. This is not me taking responsibility for that; in the way of these things, it is what the restaurateurs do, what they cook and how they serve it, their demeanour, that smile and imaginary doffed cap, that create the magic. And that’s all Michael and Maddy.

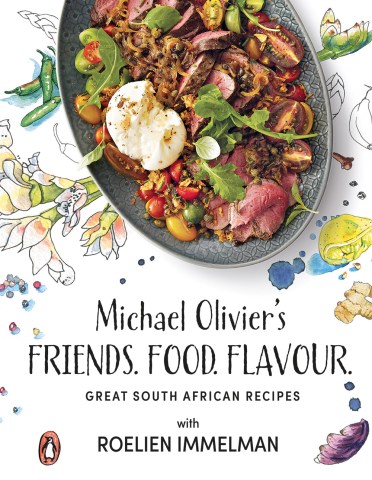

We have stayed in touch, off and on, since those days, and the other day Michael sent me a copy of his new book, Michael Olivier’s Friends. Food. Flavour. Great South African recipes, with Roelien Immelman (Penguin). What makes it special (no, I’m not in it) is the people he populates it with and the stories that the recipes tell. Most of all, a great deal of the book recalls his days at Boschendal more than at Parks, because it is very much about the old favourite Cape and country dishes that were served at the endless groaning Boschendal buffet.

The contents are presented as a buffet. Voorgeregte (first courses) such as samoosas, snoekpatee, komkommersoep (cucumber soup). But everything is given its colloquial or Afrikaans name because most of us use those names. This is because those words indicate, not just any old cucumber soup, but the komkommersoep that our antecedents made.

Soetpatats. (Photos in Michael’s book by Mike Robinson and Athabile Mpofu/ artwork by Roelien Immelman)

So, for main courses you’ll find kerrievis (yes, pickled fish, how very Cape is that), good old bobotie, and “outydse hoenderpastei”. That’s a favourite of mine, and I first ate it at, yes, Boschendal, and it correctly contains mace and cooked ham, though I was surprised to see no sago among the ingredients. There’s an “old Cape chicken curry in the style of Louis Leipoldt”, denningvleis, which is a real old Cape tradition, and waterblommetjiebredie of course. There’s cabbage bredie too (also in the Leipoldt style) and the redoubtable tomato bredie, which for me is the king of the Cape bredies. But wait, there’s more: a lamb knuckle and quince bredie, and that idea truly recalls the Leipoldt take on such dishes. A stroke of genius.

Chicken biryani. (Photos in Michael’s book by Mike Robinson and Athabile Mpofu/ artwork by Roelien Immelman)

On any good Cape buffet, and especially at Boschendal where you’d loll for hours on a sunny day, there should be many side dishes including the expected country vegetables. So there’s geel rosyntjierys, pampoenkoekies, the beloved sousboontjies, the arguably even more beloved slaphakskeentjies (sweet and sour onions), soetpatats, and boereboontjies (mashed potato with green beans). Honestly, you could fill up on that alone and with a bit of each of those on your plate alongside your hoenderpastei and tamatiebredie you could be assured of a long nap before it was time for sundowners on the stoep.

What else are we going to end this glorious Cape repast with but a slice of melktert or malvapoeding, but if we choose those, what about the gebakte appels, hertzogkoekies and koeksisters? You buy some to take home, that’s what. But we’re not actually having lunch at Boschendal, so we’ll just have to make them, and there they are, in the book.

Arroz de Pato. (Photos in Michael’s book by Mike Robinson and Athabile Mpofu/ artwork by Roelien Immelman)

Interspersed among all these jewels of Cape cuisine are other recipes Michael adores. Fattoush. Panzanella, the Italian tomato and bread salad. Dolmades. Oeufs en Meurette (Burgundian eggs in red wine). Green summer minestrone. “Simple curried eggs”. Zucchini in agrodolce. Risotto of Chicken of the Woods and Black Garlic (it’s a fungus, not actually chicken). Dalewood Wineland Wild Mushroom Brie topped with panko crumbs, enoki mushrooms, thyme and lemon pangrattato. And plenty more, including recipes by his many friends such as Mira Weiner, Mark Dodson, Nicky Fitzgerald, Ming-Cheau Lin and Prue Leith.

Catching my eye in particular were Refogado of pork neck with a Bo-Kaap spice rub, lager-baked gammon, back bacon with plums, and Arroz de Pato, or Portuguese duck rice.

Boereboontjies. (Photos in Michael’s book by Mike Robinson and Athabile Mpofu/ artwork by Roelien Immelman)

Funny how a book can pluck you from where you’re sitting and take you all the way back to the Winelands of the Eighties and Nineties, with sojourns at a table at Parks, with Michael smiling in his apron from table to table, Maddy hovering in the wings dealing with nitty-grittier matters, and me watching my wine consumption because I have to drive home.

That’s one thing that has improved. The availability of an uber so we can just chill and enjoy the thing properly. Or use the recipes in this book to recreate those days and times, right in our kitchens, then pull up chairs at the dining or kitchen table and tuck in, with a toast to old times and old and new friends. DM/TGIFood

Buy Michael Olivier’s Friends. Food. Flavour. here

Buy Michael Olivier’s Friends. Food. Flavour. here

Tony Jackman is Galliova Food Champion 2021. His book, foodSTUFF, is available in the DM Shop. Buy it here.

Follow Tony Jackman on Instagram @tony_jackman_cooks. Share your versions of his recipes with him on Instagram and he’ll see them and respond.

SUBSCRIBE to TGIFood here. Also visit the TGIFood platform, a repository of all of our food writing.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Constantia Nek restaurant…many romantic evening were spend there!

Ah, I still often (and fondly) think of Kaapse Tafel and silently hope someone someday will reopen the doors. Even in the late ’80s, it had an old-fashioned feel and was one of the few places in Cape Town where you could find traditional South African dishes. And that dessert trolley at The Townhouse! Two special restaurants.