OP-ED

The nexus of race, racism and Afrikaner identity in South Africa (Part Two)

This series seeks to establish the theoretical and historical underpinnings of the relationship between race, ethnicity, culture and space, in both colonial and post-colonial South Africa with specific reference to Afrikaners. To what extent does the phenomenon of race, as opposed to racism, give rise to socioeconomic and cultural asymmetries in society?

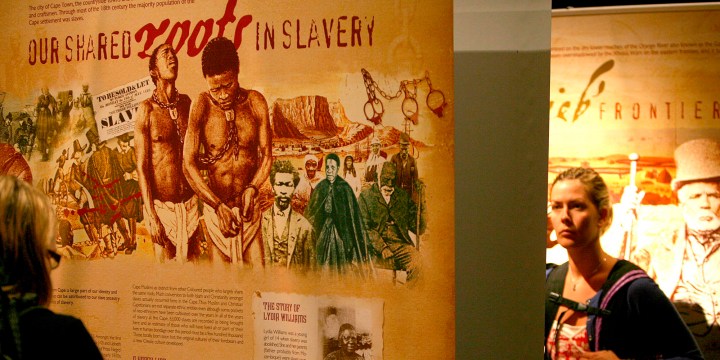

Between 1657 and 1658 a number of slaves arrived in the Cape – exported by the Portuguese from Luanda, Angola – and a number of them are believed to have been brought to the coast of Angola by slave dealers in chained gangs along trade routes stretching deep into central and southern Africa (Schoeman: 2007). This consignment of slaves, by virtue of the wide region they were collected from, represented a diverse range of African ethnic groups with different cultures, languages and dialects with very little social cohesion among them. Schoeman explains that on arrival in the Cape they did not keep their own names, as did the Guinean slaves who arrived later, who, according to Schoeman were, without exception, given European names or nicknames by the Dutch.

The Afrikaner and the identity question

Captured and indentured women were also enslaved. In December 1658, a mixed group of Heeren-Seventien (xvii) employees were captured and kept as slaves after some escaped from the settlements. In March 1660, another group of 41 convicts including free burghers also escaped. By 1717 there was an imbalance in the ratios of both enslaved and settler women. Fifteen thousand enslaved women and girls were imported from East Africa, Madagascar, Indonesia and India. “Liaisons” between locally born French Huguenots, German and Dutch settlers and free slaves were encouraged.

Williams (2021) argues that slave owners preferred light-skinned slaves, exploiting women even if it meant fathering the children themselves, in order to improve their “breed or livestock”. She stated that light-skinned slaves had a higher monetary value and served as a status symbol. According to William, the Dutch also bought Asian women on slave markets where they were advertised as “brides for sale”. Just over 1,000 captured slaves and indigenous women are recorded to have been married to settlers between 1652 and 1795, and only two former slave men are reported to have married settler women.

However, the British and the Dutch colonists refused to provide their offspring with the citizenship of their countries to enable them to assume the father’s national identity. Presumably, they were embarrassed to have had children with slave women, worse still of a different ethnic group. These children became known as “Basters” or “Baastards”.

However, on European settled farms, they were given skilled jobs such as craftsmen, and transport riders. They were also given weapons to protect and chase away the black people who were settled on some of the farmland.

This belligerent group was later joined by shipwrecked Maroons, Oorlams Afrikaners and Droster (colonial officers), banished Khoi and San, fugitives and convicts. With the blessing of their settler relatives, they became liquor traders, slave and horse riders, trading with passing ships in the Cape and the West Coast. They reported to their Cape masters/relatives on land they considered Terra nullius, inalienable and no-man’s land available for settlement by Trekboers and the British.

The Griquas were named by a British missionary, Reverend James Campbell in 1813 and their nation was established as a political, and not a cultural group in 1886. Griqualand West, Griqualand East, and Griquatown were awarded to them for their deadly frontier wars against indigenous people.

In 1992, when Patrick Tandy, Nazeem Ismael, and myself interviewed the kaptein of the Rehoboth Basters (bastards) in Namibia, who were resisting settlement of the Nama people in Rehoboth. His defence was that the land was given to the Basters in 1886 by the Germans, therefore, he did not want his ethnic group to be contaminated with blacks. Despite the fact that they were rejected by the whites who did not want to give them their ethnic or European national identities, many of the light-skinned Basters/Bastards are said to still carry their great-grandparents’ DNA. It is clear from this background, the apartheid racial categorisation notwithstanding, that it is difficult to explain and justify the logic of ethnic and blood purity of any of the South African ethnic groups – whites, coloureds, Khoi, San, and black Africans. Many of their DNA would probably show a drop of the other group’s genes, save to say some genes become more dominant than others.

The Afrikaner is predominantly of European descent, but through time and the disconnection with family roots, they have lost their mother tongue, geographic, national, and cultural identity with their European original countries. Equally, the slaves who were imported from West and Central Africa whose names were changed to European names lost their original identity, and acquired new identities.

Verwey and Quayle (2012) are cited by Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert as saying, the word “Afrikaner” means African. Therefore, it follows that to claim to be African is at the core of Afrikaner identity. In contrast, Breyten Breytenbach, as referred to by Verwey and Quayle (2012), stated that despite the fact that “Afrikaans” is just the Afrikaans word for African, in his view “he both belongs and does not belong in Africa”.

This sums up the dilemma the Afrikaner as a national or ethnic group is faced with.

The Afrikaans language developed as a common language of communication, as was the case with fanagalo, which grew from the commonly spoken languages on the mines.

The English developed their institutions and by using the missionaries they developed and promoted their culture through educational institutions. Afrikaans as a language also grew up in reaction to the English who imposed their imperial values on other groups. Therefore, Afrikaans as a language borrowed words from Dutch, French, English and even from Russian. While the name is derived from the continent of Africa, the root of the language is Dutch. Equally, the ethnic group that emerged from this amalgamation and fusion of cultures produced a single ethnic cultural identity glued together by a common language.

The Afrikaners have no problem in identifying themselves with the continent of Africa, as whites from Europe have no problem in being referred to as Europeans, and they remain proud of their national Dutch, German, French, or Belgian identity. This identity dilemma might be complicated by the race and racism concepts which are often conflated.

In November 2010, Afrikaans author Annelie Botes shocked many South Africans when she said, “Ek hou nie van swart mense nie” (I don’t like black people). In the Mail & Guardian of 26 November 2010, Botes was cited as saying “in my daily life there’s no one else that I feel threatened by except black people”.

She went further to say, “if a courier comes to my door and he is white, coloured, or Indian, I’d have no problem inviting him in for a glass of water. But I would feel threatened by a black man”. She went on to say she would never appoint a black gardener, and the reason she gave was that in her formative years in Uniondale there were no black people. “If one was walking around it was a trespassing crook. And then you must run, because he’s going to catch you.” (“In my grootwordjare op Uniondale was daar geen swartmense nie. As daar een rondloop, was dit ’n bandiet wat dros. En an moet jy hardloop, want hy sal jou vang” in Cornel Verwey and Michael Quayle: 2012).

While this statement may have caused a stir at the time, her race identity should not be substituted with her racist upbringing. In short, her race identity has nothing to do with her racist ideology. She bases her hate or dislike for black people on the white stereotype that blacks are inherently criminals, ignoring the causal relationship between poverty and criminality.

The economic inequalities in the country and the socioeconomic asymmetries are partly responsible for the increase in crime which happens to emanate from the group that experiences its negative effects the most, black people.

However, this cannot be said of PW Botha’s 1985 address to his Cabinet which was also deeply racist, and yet bordering on denouncing the very fabric of the existence of the black race, suggesting that black people are less than human. Given the office he held, this statement was not only insulting, it was dehumanising the whole race group, when he said:

“We do not pretend like other whites that we like blacks. The fact that blacks look like human beings and act like human beings do not necessarily make them sensible human beings. Hedgehogs are not porcupines and lizards are not crocodiles simply because they look alike. If God wanted us to be equal to the blacks, he would have created us all a uniform colour and intellect. But he created us differently… Intellectually, we are superior to the blacks, that has been proven beyond any reasonable doubt over years. I believe that the Afrikaner is an honest, God-fearing person, who has demonstrated practically the right way of being… It is our strong conviction, therefore, that the black is the raw material for the white man. And here is a creature that lacks foresight. The average black does not plan his life beyond a year… Let us all accept that the black man is the symbol of poverty, mental inferiority, laziness and emotional incompetence… Isn’t it plausible, therefore, that the white man is created to rule the black man?”

For me, it is this blurring of the lines between race and racism which should also be carefully watched. It is not always obvious where the boundaries of racism begin and end. However, historically, the life of the Afrikaner and their identity is interwoven with both the positive and the negative socioeconomic development of South Africa.

JC van Rooy, the chairperson of the Afrikaner Broederbond in 1944, stated that “God created the Afrikaner people with a unique language, a unique philosophy of life, and their own history and traditions in order that they might fulfil a particular calling and destiny here in the southern corner of Africa.” Van Rooy’s statement was less ambiguous about the identity of the Afrikaner and where they belong.

Conclusion

Since there is no inherent causal connection between the expression of a political ideology or ideological orientation of a person, and his/her race or national identity, and further noting that culture knows no geographic boundaries, there is equally no dialectical logic to justify the link between race, racism, and a specific geographic location. Race/ethnicity denotes a social group identifiable by their specific biological features, culture, language, religion, and values. These attributes – unlike the granting of a liquor licence which is attached to a specific geographic site – culture, language, religious values and beliefs are carried by the individuals wherever they go and are influenced by the environment within which they evolve independent of the group’s consciousness precisely because culture is not static, it is dynamic. DM

Read part one here

Dr Thozamile Botha is a member of the Stalwarts and Veterans Group of the ANC. He has a PhD in Sociology from the University of Johannesburg.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8881″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Like so many academics, the author makes the mistake of grouping Afrikaners. Afrikaners are a grouping only on home language affinity. It is the same mistake the self-aggrandising Afrikaners of Stellenbosch make when they ascribe to themselves custody of the Afrikaans language and culture. They would have a heart attack if they had to meet the Afrikaners of the cape flats 25km away that outnumber the Stellenbosch Afrikaners 20 to 1.

Trying to describe any other characteristic, whether it is racism, religion, cultural belief or anything else is a HUGE mistake. There are Afrikaners of every color, the majority are by some margin not white persons.

Even within single families there are huge differences. Take Breyten and Jan Breytenbach as a classic example.

I may as well try and write a piece about the attitudes to race and racism of the Irish.

I find some of the translations really problematic. Sure, words undergo semantic drift so they might have had different meanings at the time, e.g. “baster” or “baastards”. If you go with the English “bastard”, it’s simply children out of wedlock: a fair reason for embarrassment (at the time). If you go with the “basterdised” meaning, you’re closer to the Afrikaans meaning of “mixed”, accurate pertaining to interracial offspring. Likewise “bandiet wat dros” is quite unthreatening compared to “tresspassing crook”. Taking the “I would feel threatened” comment and turning that into “bases her hate” is also quite a dramatic change in tone. Maybe these are nitpicks or I’m missing the context from the original documents, but as just those two items already significantly colour (pardon the phrase) the conversation and take-aways.

I agree with you 100%. Whoever the author really is, he has no real idea what the differences are between Afrikaners, Afrikaans-speaking, people of Afrikaans heritage, people of mix language heritage, people with an Afrikaans language upbringing, people with an Afrikaner upbringing, etc. and the list goes on and on. Now this drama/comedy/documentary series comes in several parts, but the 1st two episodes of this “expose” is already falling short on several accounts. For example, I have to read this in English, but the number of Afrikaans-speaking (home language) South Africans outstrip the number of English speaking (home language) by a ratio of 3:1.

Now what makes this whole series of articles even more ludicrous, is that it is written by someone whose home language, or culture, is unlikely to be even remotely Afrikaans-speaking, or Afrikaner, despite having a PhD, and the surname of Botha. To top it all, he is a stalward of the ANC.

This to me is a real failure on the part of DM