OP-ED

The nexus of race, racism and Afrikaner identity in South Africa (Part One)

This series seeks to establish the theoretical and historical underpinnings of the relationship between race, ethnicity, culture and space in both colonial and post-colonial South Africa, with specific reference to Afrikaners. To what extent does the phenomenon of race, as opposed to racism, give rise to socioeconomic and cultural asymmetries in society?

Is there any rational logic for the Afrikaner to strive for cultural autonomy to be exercised in a separate geographic space within South Africa? It is my view that the logic of race/ethnic identity cannot be explained without analysing the context of a people’s economic and historical sociocultural evolution.

Plato, cited by Blackburn (2006:30), argues that custom or ethos arises in the way we have imagined conformities arising as we coordinate on things like rituals, or patterns that enable us to cooperate. He goes on to assert that laws enacted by reason shape custom, but they cannot exist without it. Plato discouraged the presumptuous thinking, in this area and others, that reason can float free of its earthly and earthy constraints in nature and custom.

It is the analysis of the dialectical logic of the contradictions inherent in an object which provides concrete answers to complex problems. Race is not only a social construct, it is also, using EV Ilyenkov’s (1977:320) analysis, a concrete unity of mutually exclusive opposites, which is the nucleus of dialectics. This draws a distinction between a theoretical determination of an object such as value created by labour or the surplus value of labour power in the process of production, and the surplus value resulting from class exploitation where race is a coincidence and not the cause.

A good example of this is what Engels observed in the streets of Manchester in the 1840s, where the Irish workers lived in dirty streets and squalor driven by class exploitation and not necessarily by race. Class and race are mutually exclusive to the extent that race is not a precondition for wealth creation, but capital accumulation feeds on racism.

However, racism with its contradictory identity raises the question of whether its existence is derived from any dialectical logic and whether striving for social cohesion where racism is a major factor is a logical outcome. It is the intention of the writer to test the validity of this theory against the historical experiences of the racially and culturally diverse South African rainbow nation within the realm of a geographically integrated economy, and the cultural-autonomy discourse.

According to Proudhon (1840), the necessity of finding a compensation for the misery resulting in every nation, from abroad in the absence of economic equilibrium locally, is “real, though, an ever-concealed cause of war” (Proudhon, 1840:13). In the South African context, the cause of civil war, viewed from the perspective of race and ethnicity, may be located in the misery of poverty, economic inequalities, and the disconnect between the black Africans and land.

Meanwhile, some among the white population view this issue differently: for them the basis of civil war might be the failure of the black government to adhere to their request for the right to cultural autonomy and a separate territory where such autonomy will be exercised. Therefore, to avoid or stop the potential for racial conflict is to find a discursive rational middle road. Historically, the reasons the Afrikaners identified as the cause of the black struggle for political and economic emancipation was a communist-driven agenda. Therefore, all their strategies were designed to divert attention from the real causes of the conflict to external factors, thus ignoring the real internal issues.

Contrary to this argument, it is the absence of economic equilibrium which can be attributable to the ethnically and racially accumulated wealth using racial capitalism to enrich a race-based Afrikaner ethnic group. The negotiated Constitution of 1996 and the Bill of Rights were drafted to provide a mechanism by which the state can intervene to assist in ameliorating the economic misery in search of economic and sociocultural equilibrium. Driven by the desire to attain social cohesion, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa continued to protect individual private property rights and accumulated wealth, regardless of how it was acquired.

The rationale for this was not to condone what racism did, instead it was to enable the parties who were engaged in the civil war to develop self-corrective measures without coercion. The objective was driven by the desire to build the elusive rainbow nation ideal.

Some of the strategies intended to address the aspirations of mitigating the resultant inequality and misery which is caused by poverty, partly arise from the post-apartheid inherited economic structure, exacerbated by the poor management of the economy by the neoliberal black elite as well as by corruption. While racism is an active expression of the differences between the ethnic groups, it cannot be held liable for all the economic misery the majority of the population faces.

The racist differences pointed out are neither scientifically nor religiously justifiable, except they are a social and political construct relevant to a specific historical moment. Racism is not a unilinear phenomenon, it mutates and presents itself in different forms and shapes and it cuts across all racial/ethnic groups whatever their racial identities.

In essence, race is a concrete example of a mutually exclusive unity of opposites where class and race coexist to produce a specific identity, relevant to a specific historic moment, taking advantage of race/ethnic power relations to advance narrow capital accumulation.

The effects of the 1913 Land Act

The effects of the 1913 Land Act went far beyond addressing just the race/ethnic question, the racist motive of the Afrikaners coincided with the promotion of their class interests. Race and ethnic differences were manipulated to serve class interests. A good example of this strategy is demonstrated through the way the Afrikaners and the Broederbond conducted their business within the National Party in pursuit of the combination of their ethnic and class interests, at the expense of other groups. Characterising the Broederbond strategy, Lindie Koorts sums it up as follows:

“The non-purified sections of the National Party who were known not to sympathise with purified politics or known to be active Fusionists were simply ignored and shunned as apostate brothers and kept in the dark as much as possible as to what was transpiring in the politics of the country.”

The objectives pursued by the Afrikaners were achievable provided each ethnic/racial community member acknowledged its rights and obligations to the other and its related limitations. Alternatively, they could be achieved by means of coercive force. Society expects that those who are privileged will assist the disadvantaged and poverty stricken within the ambit of the ethnic or racial classification. This view is premised on the notion that poverty is not only determined on the basis of race or ethnic classification, it is also determined within the realm of the political, economic, and the social continuum.

The success of poverty alleviation is contingent upon mutual respect between the dominant social classes in society, and the recognition of each other’s contribution in the development of the economy, while being cognizant of one another’s vulnerabilities. This contingency has to take into account the essence of the existential dependency relations between labour and capital, cognizant that race is incidental to the equation rather than being the cause of creating the socioeconomic hierarchy.

The black community and the media in general interpret the 1913 Land Act as a fundamental cause of land dispossession in South Africa (Beinart and Delius, 2015:24). A Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) statement cited by Beinart and Delius (2015:24), stated that “at the stroke of a pen, the majority of the population were cruelly robbed of their land, the source of their food and the site of their families’ homes for generations.”

Meanwhile, Beinart and Delius read the purpose of the 1913 Land Act as if it was an “interim measure [which was designed] to maintain the status quo of land occupation and ownership…” They argued that it was recognised by most in the 1910 Union government, particularly by the Native Affairs Department (NAD), that more land would have to be set aside for black African settlements. This interpretation of the 1913 Land Act has to be viewed against the background that the status quo of land ownership was racialised, the bulk of the land was divided between the English and the Afrikaner ethnic groups of European origin.

The 1913 Land Act was not meant to dislodge African people from land they occupied in customary tenure or owned in private tenure, instead, according to Beinart and Delius, the Act was designed to change the terms on which Africans could occupy white-owned land, by extending the areas already reserved for African communal ownership.

The Act set aside preconditions for undermining the African labour tenancy, it further segregated the land, and marginalised Africans in the reserves. The 1923 Native Urban Areas Act defined urban blacks as “temporary sojourners” who were welcome in the urban space only insofar as they ministered “to the wants of the white population” (1923 Native Urban Areas Act). This is an illustration of the nefarious intentions of the 1913 Land Act which was an expression of the contradictions of the unity of the mutually exclusive opposites, race and class, coexisting in the objectives of the act and the mission of racial capitalism.

As Plato identified, “a threefold support to the idea of law, which are: nature, custom, and reason” (Blackburn, 1972: 30). He argued that “nature gives us purely animal material with which custom or culture, and reason, have to work. Custom or ethos arises in the way we have imagined conformities arising as we coordinate things like rituals, or patterns that enable us to operate” (Blackburn, 1972: 30).

Race, ethnicity and national identity

One of the Afrikaner members of the Afrikaner Africa Initiative (AAI) wrote recently:

“The more Afrikaners become Afrikaners again, the better our engagement with other communities becomes: an agricultural project in collaboration with Princess Gabo of the Barolong Boo Seleke; new relations with the Zulu king; the relationship with the Zulu community at Nkungumathe; the struggle for a school for the Nkandla community; beautiful new relationships with the Khoisan and other Afrikaans communities; and the wonderful relationship with the Mbeki Foundation.”

The above text establishes a principle that before one extends a hand of help to others he/she must first make sure that his/her own house is built on solid foundation.

It might be of interest to contrast the first line of the above quotation with what Professor Njabulo Ndebele said in reference to Chinua Achebe’s novel No Longer At Ease, written in 1960, which narrates the story of an Igbo man, Obi Okonkwo, who left his village for a British education and a position in the Nigerian colonial civil service.

According to Achebe, Okonkwo struggled to adapt and fit into the Western lifestyle. Ndebele draws a parallel between Achebe’s story and TS Eliot’s poem, The Journey of the Magi, which Ndebele recites thus: “We returned to our places, these Kingdoms, But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, With an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death.” – Alex Dodd (30 September 2014)

This sounds like an expression of despair from a person who still loves his culture but has progressed beyond the static traditional culture of his village because for him culture is not restricted to geographic space. This emerged from a debate between three professors: Prof Harry Garuba, Prof Njabulo Ndebele, and Prof Sarah Nuttall on the topic of race and identity politics in the John Berndt Thought Space on 18 September 2014, hosted by the Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative, University of Cape Town.

The above debate brings to the fore the issue of the clash of cultures and the challenges people experience to adapt to conditions of change even within their own historical environmental settings separated by the lapse of time.

A professor friend of mine at one of the Gauteng universities questioned me about the rigidity or not of black African ethnic and cultural identity. He asserted that a large number of the Gauteng black African population – in Johannesburg in particular – no longer have relations with the birthplace of their parents and grandparents in rural South Africa. Some of them are the third and fourth generation living in Gauteng, with little or no connection at all with their roots except the knowledge that their ethnic group is Xhosa, Sotho or Zulu. They don’t even speak their mother tongue fluently as they have been influenced by the languages spoken in Gauteng.

Therefore, these third- or fourth-generation Gauteng citizens can no longer be assigned to any particular province as their cultural home other than Gauteng. Even if one tried to impose that identity by virtue of ethnicity, “they will no longer be at ease here”; everything is alien to them. This raises the same question about Afrikaans-speaking South Africans and their relationship with Europe.

This suggests that national and cultural identity should not only be defined by geographic space. An evolving ethnic and cultural dynamic plays a significant role in defining social values that create uniqueness, and diversity among ethnic groups independent of the geographic space of their parents. The reference to Magi’s paradox where he is happy “to return to our places… but no longer at ease here”, suggests that culturally things have changed so much that he no longer fits in the society of his birth. In a sense he is a stranger in a place which his parents called home.

This is consistent with Breyten Breytenbach’s confession that he “belongs and does not belong in Africa”. This is a problem of national identity similar to some Afrikaners who claim to be Africans, but have a problem in calling themselves South Africans.

It is a fact that from a race perspective, there are Afrikaners who are still looking to return to the old Kingdom, just like there are black Africans who would selectively prefer to return to the past if only they could swap their economic position with whites.

It is interesting to note that at the end of the 19th century Africans organised themselves and “worked with whites who were sympathetic to their cause to secure an expanding role in what they believed was an evolving British system that could result eventually in fully nonracial representative government” (Karis, T and Carter, GM, Volume 1, 1972:8). These Africans were seduced by the slogan “equal rights for every civilised man south of the Zambezi” which was a guide to legitimate political activity. They assumed that the word “civilised’ was inclusive of them. They, however, ignored the fact that the author was Cecil John Rhodes, who “intended it first, for Afrikaners, then coloureds, and only ambiguously for Africans” (Karis and Carter, 1972:8).

These contradictory objectives and interpretations characterise the complex concept of unity in diversity and social cohesion. The diverse views and interpretations of society are not only characteristic of the Afrikaner community, they are a reflection of the complexity of the human mindset of people and leaders in society. Tukufu Zuberi, a social statistician from the Sociology Department of the University of Pennsylvania, giving the Martin Luther King Jr Lecture, stated that “race is only a cause in the process when the structure of race is a subject of discussion”.

This should be seen in the context of a narrative of the relationship between nations and among nations themselves (Zuberi). He further argued that stratification exists in every society that has race and ethnicity. However, the issue arises in the process of explaining the causes of stratification in society, then race and ethnicity become a subject of discussion. The history and the ethnography of where we think we came from becomes the starting point of the discussion of race and ethnicity in the attempt to explain the stratification of society. Race is not genetic, hence his argument that race is not an illusion and, secondly, it is not a system of colour coding. It is a process of thinking through a European logic by classifying people who are not white, black. This social classification is meant to construct a narrative and a mindset which seeks to justify that people who are not white have a lower intelligence quotient (IQ) than whites.

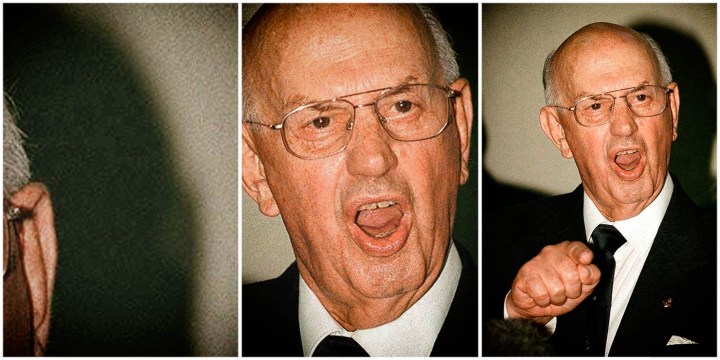

Koorts (2014: xii) in her biography of DF Malan, makes the observation that what biography strives to achieve is to “enable a contemporary reader to share in this understanding of the past, disagreeable though it may be at times, without any attempt at apology or justification”, noting that biography is part of the history from the lived experience of the individual.

The concept of autonomous cultural community presupposes a group of mutually respecting people sharing a territory, common language, culture, belief systems, and shared values. A cultural community implies some degree of relative close proximity of members of the community sharing a common language and value system. This necessitates the building of institutions designed to support and promote the group culture, cultural artifacts, and a people’s language in order to sustain coherence and consistency.

However, cultural identity is never pursued for its own sake, its underlying objective is always to create geographic and social spaces within which the practice of group and subgroup cultures can be exercised peacefully. Therefore, if “Magi is no longer at ease” in that geographic and cultural space, does forcing him/her to that space still help to build social cohesion and free him from the cultural straitjacket? It seems to me that a person forced into that situation, like Magi, should be “glad of another death”. In the case of South Africa, another death could mean declaration of a civil war which the Constitution sought to prevent.

The tension arises in instances where two diverse communities are pursuing two different sets of agendas such as Afrikaners seeking cultural self-determination in terms of section 235 of the 1996 Constitution, while black Africans are still striving for economic equality to reverse the effects of the 1913 Land Act. This presents the contradictions in the concept of social cohesion without at the same time offering solutions to the economic asymmetries between the racial groups that have grown apart for centuries. DM

Dr Thozamile Botha is a member of the Stalwarts and Veterans Group of the ANC. He has a PhD in Sociology from the University of Johannesburg.

Read Part Two here.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8881″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.