Maverick Citizen: Solutions to unemployment

Government taking on the role of employer of last resort can solve South Africa’s jobs crisis

An employer of last resort programme will aim to provide unemployed workers with jobs that fit their skills if they are willing and able to work, and in the process provide public goods and services. Funding this under tight fiscal constraints can be accommodated by reordering priorities.

Almost everyone acknowledges that South Africa faces an unemployment problem. Just how bad is it?

According to the latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) the unemployment rate now stands at 34.9%. But this figure only serves to understate the real extent of unemployment. When discouraged workers are included, the expanded unemployment rate rises to 46.6% – but even this figure doesn’t capture the true extent of unemployment in South Africa.

Of the country’s working-age population of 39.7 million only 14.3 million are considered to be employed. That means only 36% of the population that is of working age (between 15 and 64) is in some form of employment. This figure does not specify the nature of employment. It includes people who are in temporary or casual employment and those working piece jobs. To be considered employed one only had to work a total of one hour in the week in which the survey was conducted.

South Africa’s unemployment problem is a structural problem. It can be traced back to the country’s history of apartheid and the nature of the development of its economy. This structural unemployment also needs to be understood in relation to the macroeconomic policies implemented by the post-apartheid government.

Until the early 1970s, South Africa experienced growth-enhancing structural transformation. Thereafter it entered a period of premature de-industrialisation, due to a confluence of factors, including low productivity, increasing reliance on expensive imports and poor export performance. In the post-apartheid era, South Africa has found itself in a long-run growth trap, with growth in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors notably absent from the economy. This has resulted in stubbornly high unemployment rates, due to an inability of the economy to absorb excess labour supply.

The Groundbreakers feeding programme in Ocean View helps many vulnerable families. Many residents rely on the one meal they receive daily from Groundbreakers due to unemployment. (Photo: EPA-EFE/NIC BOTHMA)

In the two decades following the end of apartheid South Africa’s growth path has also been characterised by a rapid relative expansion in the services (or tertiary) sector. It has shifted increasingly towards the provision of services, in particular that of financial and business services, while its labour-intensive productive sectors such as manufacturing, mining and agriculture have stagnated and declined.

While the ANC-led government made some limited gains in strengthening its pro-poor policies, the high levels of poverty, unemployment and inequality forged under the apartheid regime still remain.

Government interventions

Since the transition to democracy in 1994, the government has attempted to address the high unemployment rate and poor living standards by rolling out a number of job-creation programmes as well as an extensive system of social grants. The latter has grown rapidly over the years. In 2000, about 3.9 million people out of a total population of 44.5 million received a grant, equating to 9% of the population. By 2019 the number of total beneficiaries was up to 18.2 million, or 31% of the total population.

Across the world there has been a drive towards public works programmes (PWPs) over transfer-based social protection. In South Africa three such programmes have been rolled out since 1994: the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) from 1994 to 1999, the Special Poverty Relief Allocation (SPRA) from 1999 to 2004, and the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) from 2004 onwards.

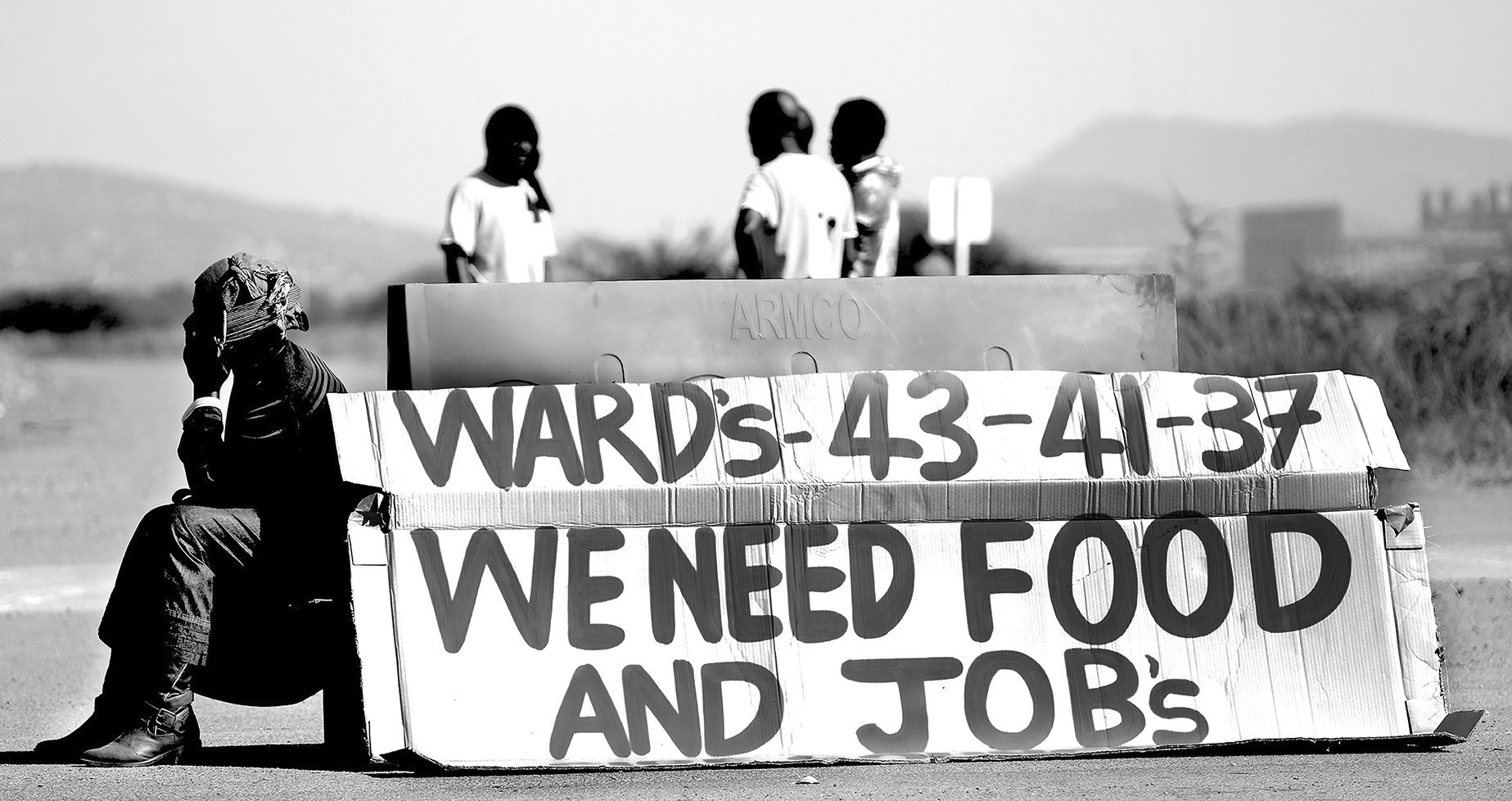

About 200 men wait for work in the informal sector at a road junction in Cape Town on 24 June 2020. (Photo: EPA-EFE/NIC BOTHMA)

The first phase of the EPWP from 2004 to 2009 took a cautious approach and was small in relation to the scale of the problem, mainly due to scepticism over whether it would work. The institutional issues experienced with the previous two programmes (the RDP and SPRA) influenced its design. In this regard, there was an increase in budgets as well as motivation for them to be in line with their respective departments. There was also an aim to address priority areas, in particular deficits in infrastructure, social services and environmental services, and to do this without undermining the public sector.

Key design features of this programme included:

- All levels of government (national, provincial, local) were expected to contribute to the target of creating one million work opportunities over five years;

- Income and training were provided, enabling people to move into other work;

- A special employment framework (to distinguish from public sector and formal employment – maximum employment duration, allowance for low wages, training, no unemployment insurance);

- Focus was placed on four sectors for implementation – infrastructure (roads, water, parks), environment (fire, wetlands, alien vegetation), social (child, home and community-based care), and economic (small enterprise development).

The target of creating one million work opportunities was met one year ahead of schedule. Work opportunities are only temporary, and thus one million work opportunities equates to only 650,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs) or “real jobs”. It was considered that while there was a general decline in the rate of unemployment over the span of the first phase (from 29.5% to 23.5%), the scale of the programme needed to be expanded significantly to properly address the problem.

People from the Seraleng mining community in Rustenburg protest over unemployment, loss of business and access to a social labour plan. (Photo: Gallo Images/Dino Lloyd)

Alongside this there was a range of issues that were identified to be addressed in subsequent phases. The duration of jobs was shorter than expected, meaning less income and less work experience for participants. Training targets were too ambitious and couldn’t be met. Wages remained static while other costs rose – in some areas wages were so low as to not make any meaningful difference to people’s lives. Differing wages and employment conditions created difficulties. And finally, implementation measures differed in performance, with those in areas of need especially limited.

The second phase of the EPWP from 2009 to 2014 set a new five-year target of creating 4.5 million work opportunities (two million FTEs). However, it only ended up reaching 91% of this target, creating 4.1 million work opportunities. While labour intensity increased steadily during this phase, it was considered that there remained too much focus on employment targets, to the detriment of other areas of the programme.

Phase three of the EPWP, from 2014 to 2019, set a target of creating six million opportunities (2.6 million FTEs). However, it only reached 73.2% of its target over the five years, creating 4.4 million work opportunities.

The current phase four of the EPWP, running from 2019 to 2024, has been scaled back rather than expanded, and will target the reporting of at least five million work opportunities (2.4 million FTEs) – this while unemployment figures continue to soar.

Limitations of public works programmes

The issues identified at the end of the first phase have continued to plague the EPWP, even though a minimum wage has subsequently been introduced for EPWP workers. These issues, however, are not specific to the EPWP. Inadequacies with PWPs the world over are recognised. These inadequacies have been attributed to poor theorisation and design features that include low wages, short-term employment, small-scale coverage and duration, poor-quality asset creation, limited training and institutional constraints.

If there are workers who are ready and willing to work at the ELR wage, the government can always afford to hire them. (Photo: Adobe Stock)

PWPs, like the EPWP, have gained popularity based on certain assumptions operating at three levels. First, at the microeconomic level, they are seen to promote household productivity without inducing dependency, provide a wage transfer (as opposed to a cash transfer), foster skill and asset creation, and assist in graduating people out of poverty. Second, at a macroeconomic level, they are seen to stimulate demand (by injecting cash into the economy), to create productivity-enhancing assets, and to contribute to national growth. Last, at a sociopolitical level, they are seen to function as political and social stabilisers. However, in practice there is inadequate evidence of significant or sustained impact in addressing the issues beyond basic consumption smoothing.

What is clear is that projects such as the EPWP are not ambitious enough to address the structural nature of the unemployment problem in South Africa. It is concerning that even these stopgap measures appear to have reached their limits and are in the process of being scaled back.

An alternative government intervention

There are alternative programmes and policies that the government could consider implementing to meaningfully address unemployment. An employer of last resort (ELR) programme is one. It goes beyond transfer-based solutions and conventional PWPs, aiming to ensure that anyone who is willing and able to work has the chance to do so.

The ELR is envisioned as a government-implemented programme that creates jobs at a minimum wage for those who cannot otherwise find work. It is seen as a permanent programme, not a temporary or emergency one. An ELR programme is also not seen as a substitute for private sector employment, rather it is intended to complement private employment. Such an ELR programme is made even more desirable in that it has the potential to lend stability to a country’s economy – but only if it is rolled out in an extensive, albeit complementary, fashion, and on a permanent basis.

This kind of programme was first proposed by an American economist Hyman Minsky. To achieve stability and eliminate poverty within the capitalist system, Minsky suggested an ELR programme whereby the government would take unemployed workers as they are and provide them with jobs that fit their skills. An ELR programme would see the government employ all unemployed workers who are willing and able to work. This would need to be implemented at a national level, since only the national government is in the position to offer an “infinitely elastic” demand for labour and ensure that anyone that is willing to work at the going wage would be able to get a job.

In addition to an ELR programme providing jobs in places where they are most needed and to the people most in need, it would also provide public goods and services. It would be able to provide these interventions directly in poorer areas. Providing these kinds of jobs for all would help to affirm the dignity of labour and allow everyone who so desired the chance to participate more fully in the economy.

Financing the programme

The financing of an ELR would not require private debt and speculative finance, thus it wouldn’t foster speculative booms. This would allow greater stability of demand and output to be achieved. Minsky maintained that a national government that has adopted a floating exchange rate is able to offer infinitely elastic demand for labour, without having to worry about affordability issues.

He also argued that ELR would not be inflationary once it was in place. Inflation would only be a temporary issue in the early stages of the programme as the move towards full employment would mean the raising of wages and consumption patterns. This would be inflationary as it would increase aggregate demand and lead to some price increases. However, maintaining full employment with an ELR programme does not have the same inflationary impact as moving to full employment and would not result in permanent inflation.

L Randall Wray is another American economist who has developed Minsky’s proposals, particularly in relation to developing countries. He argues that a sovereign government operating with its own floating exchange rate can always financially afford an ELR programme. Most developed countries now operate with floating currencies, as do a number of developing ones, including South Africa.

The only major foreseeable implication of financing a new ELR programme, for a sovereign country with a floating currency, would be a possible increase in government spending. However, this net increase in spending would be relatively small. For a country like South Africa, it would likely be in the region of 1% of GDP, as was the case with the Jefes ELR programme in Argentina and India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

Senior citizens queue for their monthly social grants outside Jabulani Mall in Soweto. (Photo: Gallo Images / ER Lombard)

This amount already exceeds that spent by governments of many countries in their attempts to fight poverty and unemployment. Even if governments are to be believed that they are operating against tight fiscal constraints, an ELR programme can be undertaken by reordering priorities.

According to Minsky and Wray, a sovereign country operating with a floating exchange rate can always financially afford an ELR programme. If there are workers who are ready and willing to work at the ELR wage, the government can always afford to hire them. It pays these wages by crediting bank accounts, and if it credits more accounts than it debits through taxation then a deficit arises. This takes the form of credits to the banking system, held as reserves. If the reserve holdings are excessive then banks bid the overnight rate down. A government can let the overnight rate fall to zero or it can intervene to sell interest-paying bonds at the desired support rate, draining the excess reserves.

This shows that government spending on ELR is not constrained either by tax revenues or demand for its bonds. DM/MC

Dominic Brown is economic justice programme manager at the Alternative Information & Development Centre (AIDC). The AIDC aims to produce and promote alternative knowledge and analysis which enables popular movements for social, economic and ecological justice to engage with the intersecting crises flowing from the natural, economic and social challenges confronting humanity.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This sounds great in theory, but when you look at the numbers it is not feasible. There are 25 million unemployed (from the figures given in this article), at just R1000 / month, that comes to R25 billion per month, which is R300 billion per year, which would be the largest budget item.

The solution to this affordability problem given in the article is effectively to devalue our currency. Unfortunately that has been tried many times before, not least of all in Zimbabwe and the results are well known and disastrous.

Rejigging spending to that extent would have massive impacts on society and the economy.

Maybe if they replaced social grants with “social jobs” (jobs that benefit society to earn your social grant) for those that are able…