MATTERS OF OBSESSION

So, you’ve never heard of Reuben T. Caluza? That needs to change

Released on Heritage Day, Miller and Moeng’s digital album, Reuben T. Caluza, The B-Side, celebrates the ever-poignant works of an iconic, yet largely forgotten South African composer.

“So, you’ve never heard of Reuben Caluza?” the press release accompanying Philip Miller and Tshegofatso Moeng’s new digital album asks us. Well… that needs to change. And it’s about to.

Titled Rueben T. Caluza, The B-Side, the album celebrates original songs written in the 1920-30s by one of South Africa’s most accomplished composers. Released on Heritage Day, 24 September (and available to stream on SAMRO’s website, as well as on Bandcamp), The B-Side is a dynamic re-arrangement and revitalisation of Caluza’s hit songs that were featured in The Double Quartet, one of the only known recordings of Caluza’s work, created in London in 1930.

It is both a celebration of a South African genius as well as a rumination on the complexities of history and how it continues to live on in the present.

Nokuthula Magubane and Ann Masina. Image: Courtesy of Philip Miller and Tshegofatso Moeng.

The album is also the fruit of true collaboration. Composed and rearranged by Philip Miller – internationally acclaimed composer and sound artist who is perhaps most famous for his collaborations with contemporary artist, William Kentridge – and Tshegofatso Moeng, an accomplished singer, Fulbright recipient, and music scholar – the creation of the album must also be partly credited to the singers and musicians who were deeply involved in the evolution of the project, and who Miller refers to as his “musical family.” This includes South African singers Ayanda Eleki, Ann Masina, Bulelani Madondile, Nokuthula Magubane, Lydia Manyama, Rueben Mbonambi, Lulama Mgceleza, Zebulon Mmusi, Mapule Moloi, Lindokuhle Thabede, and Lubabalo Velebayi. As well as jazz instrumentalists Adam Howard, Dan Selsoc, Lwando Gogwana and Thembinkosi Mavimbela. Video designer, Marcos Martins, was central to the creation of the poignant music videos that accompany some of the songs.

But, to return to a central question, who was Reuben T. Caluza? Despite his alleged status as a “household name” in South Africa in the early 1900s, and his title as “one of South Africa’s most accomplished composers”, (as The B-Side describes him), many of us may not have even heard Caluza’s name before. And why, if he has been so long forgotten, should we be making an effort to remember him now?

The legacy of Reuben T. Caluza

In the layers of time and history that have been stacked on top of each other since Caluza was creating music (including, of course, the many years of apartheid during which most forms of non-white culture were tragically suppressed and devalued), the composer’s work has managed to fall through the cracks of mainstream South African musical history.

Tshegofatso Moeng in action. Image: Courtesy of Philip Miller and Tshegofatso Moeng.

“Wow, there is a world of music by Caluza that we never really covered in music school,” said Moeng, recalling his introduction to Caluza’s work. “He was an internationalist and he’s well-known and studied in American universities, but we are not exposed to him here.”

Miller agrees: “In the music repertoire that students go into in South Africa, there is very little about Caluza. But then at places like the University of Texas, there are musicologists and professors who teach whole courses on Caluza. It’s extraordinary. Hopefully this [The B-Side] might bring some awareness back.”

Caluza was born near Edendale, KwaZulu-Natal (then called Natal) in 1895, and, according to this short biography, displayed musical talent at a very early age. His talent was further developed in secondary school, when he attended John Dube’s Ohlange High School, the first school founded by a black South African, and one of the first institutions of higher learning for people of colour. Later, he spent time in America, where he studied music at Hampton University and then Columbia University, after which he returned to South Africa to be appointed the head of Adams College School of Music.

It was in America that Caluza first encountered ragtime, a genre which originated in African American musical communities and is sometimes credited as a precursor to jazz. Miller expands: “This influence of ragtime had a big impact: Caluza was instrumental in developing and revolutionising the ‘concert form’, freeing it up from static missionary choral performance and rather combining movement/dancing with singing performance, relating to the action-songs of isicathamiya, which became a central part of concert entertainment in South African choral music.”

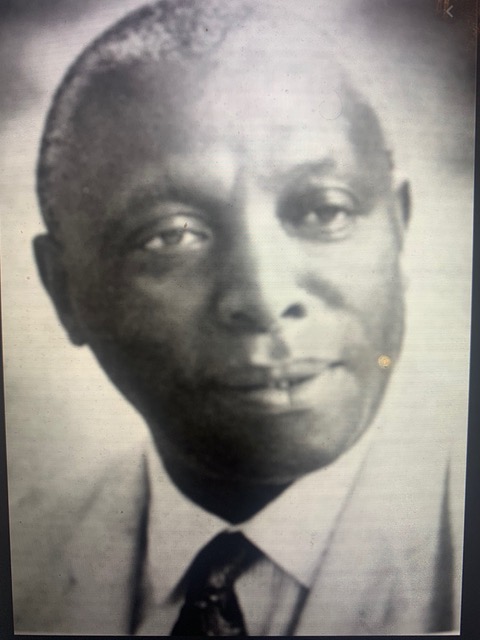

Reuben T. Caluza. Photographer unknown. Image: Supplied.

Further, and importantly, Caluza was associated with the New African Movement, a black modernist intellectual movement of the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the wake of British arrival in South Africa, which brought with it the technologies of capitalist modernity and missionary Christian teachings, the New African Movement consisted of a group of intellectuals who attempted to reconcile traditional ways of thinking with the practices and perspectives of modernity.

In his book, An Outline of the New African Movement in South Africa, Ntongela Masilela describes the “central nature” of the movement as “liberation and decolonisation by challenging, contesting and decentralising the hegemonic form of European modernity that was occupying the cultural geography and the social topography” of South Africa.

Caluza’s intellectual involvement in this movement was reflected in his music, which was, more often than not, political and anti-colonial. So not only was Caluza revolutionising the very form of choral movement (as Moeng puts it, “he was never really writing just your normal ‘choral sound’. He was always pushing boundaries”), but he was revolutionary in the content of his songs.

In The B-Side, Moeng and Miller have continued where Caluza left off by leaning into the boundary-pushing aspects of the original album in their rearrangements. “Sometimes the ear might go ‘hmm… that’s harsh’”, Moeng explains about the clashes in the songs of The B-Side, “because choral music is all simple harmonies. But with this [The B-Side], there is a lot going on. You definitely need to listen a few times.”

The reinvigoration of this great composer’s work shows us another thing: the haunting parallels of a dark history with the realities of today. The issues that Caluza tackled in The Double Quartet live on. As Miller puts it, Caluza’s music makes “just as much impact in the contemporary moment. It makes as much impact as any contemporary piece today”. Perhaps The B-Side can help us understand that not only does South Africa still suffer from the wounds of its history, but the issues of today are directly tied to those of yesterday.

Ayanda Eleki and Lubabalo Velebayi. Image: Courtesy of Philip Miller and Tshegofatso Moeng.

History doesn’t repeat – it rhymes

While The B-Side might sound very different from its inspiration (Caluza’s original, The Double Quartet) and the issues that are tackled in the songs may manifest in new ways, there is no denying the source of either.

“While they [the lyrics in Caluza’s songs] were written in the early twentieth century, you look at the lyrics and it seems like it’s happening right now,” says Moeng.

Case in point is the very inception of the project, the first song of Caluza’s that Miller revived, titled Influenza 1918. Miller explains how he came across Caluza’s name for the first time in this article written by Mark Gevisser, which traces the way that the South African government has dealt with epidemics in the past. Gevisser talks of “epidemic expediency” and how, historically, the South African government has utilised the panic and rhetoric that surrounds disease outbreaks to racially segregate the nation’s population.

Caluza’s original Influenza 1918 was a lament of the Spanish flu outbreak in 1918 that took the lives of about 300,000 South Africans. To Miller, who came across the song in our first lockdown of 2020, the composition really hit home. After extensive research, and with the help of musicologist Veit Erlmann, amongst others, Miller gathered his “musical family”, then rearranged and produced a new version of the song, all entirely remotely.

While Caluza wrote in 1918 about the Spanish influenza, and Miller rearranged in 2021 in light of Covid-19, the loss and pain (as well as little glimpses of hope) experienced and expressed in the two pandemics is painfully parallel. Not to mention the reality of the gross inequalities in South Africa that both pandemics exposed. A historical rhyme.

The B-Side cover. Image: Supplied

Miller mentions another song in the album, titled iLand Act 1913, written about the Land Act that was passed in 1913 which denied black people the right to purchase land. Of course, this law had a devastating ripple effect on the black population of South Africa, and its ramifications are still felt today.

“Expropriation without compensation. It’s now, it’s happening,” expands Miller. “Remember that terrible scene that happened last year,” he said, referencing the horrific moment when the City of Cape Town’s Anti-Land Invasion Unit was caught on video dragging a naked man from his shack in Khayelitsha, allegedly because the man was illegally occupying the land on which his shack was built.

The archive

It’s not difficult to see the necessity of digging into the past, of remembering and revitalising Caluza’s work. As Thula Magubane, one of the 12 singers involved in the project told Daily Maverick in an earlier interview, “we are chain reactions, and we must not repeat the mistakes of history”.

Nokuthula Magubane. Image: Courtesy of Philip Miller and Tshegofatso Moeng.

History, and the archival documentation of it, can change the way we view and act within the world today. Remembering a great composer like Caluza, whose powerful and important work was almost lost in the folds of history, is vital in our understanding and investment in our present-day South Africa.

The most recent video in the album, made by Marcos Martin and titled uDalimedi, is a fascinatingly nuanced take on the form and role of archives in the digital age. In the short film, a rearranged Caluza song plays over artfully animated footage of the WhatsApp group chat that the artists involved in the making of The B-Side used to communicate throughout the album’s creation. Overtime, the WhatsApp chat, which the artists initially utilised for sending music and recordings, but also to update each other on day-to-day life, grew into what Miller realised is “an extraordinary archive of the entire process”.

Martins explains the conceptual reason behind using the Whatsapp footage: “Covid brought an awareness to us of many things that we took for granted or didn’t realise we were doing. One of these things is the fact that we experience so much through conversations on chats. More now than ever, it’s less in the open air, or in encounters, but over chats that we get to know things… like the birthday of someone, or that there was a man who was taken by the police. All of this gets concentrated in one single media which is, in this case, the WhatsApp stream of conversation. You end up creating this second life that is all about narrative. It highlights the fact that every event exists in narration.”

Footage of a WhatsApp chat might sound like it could make for a terribly dull music video, but Martins’ dynamic use of movement and animation, the ebb and flow of impossibly speedy scrolling, flashes of halted emojis, and sections of zoomed-in, readable text, truly brings this example of a digital archive alive.

It’s also “talking about the speed with which we discard information these days”, explains Martins. “Because we just browse very fast through all these events. So, when I pause on some of these icons, these emojis, it’s a way of saying, look how we pass through these things without actually paying attention to each and every piece of information we are loaded with”.

The digital archive of the WhatsApp group is paired with the reconfigured and digitised Caluza song, which, Moeng explains, has only one poignant lyric, chanted over and over again. “The whole song has one sentence, which means, ‘listen to the dynamite going off under the mountain’. That sentence has so much… You can read it in so many ways, in that there is something brewing, something is going on under the surface, something is about to explode. It speaks so much about the world and what is happening in our country.”

Community and improvisation

The uDalimedi video also reminds us that it was a close-knit community, a “musical family”, that made this important project possible. “Working on this has taught me that together we are powerful, even when we are physically apart,” Magubane told Daily Maverick.

Which is why it is important to note that improvisation played a critical role in the reconfiguration of Caluza’s songs – all of the artists involved, singers, jazz musicians, and composers alike – were invited to add their own flair to the music.

“That is how Philip [Miller] likes to work. That is how he always works,” says Moeng. “He is open to interpretations. If you do something that is cooler than what he wrote… well then, go for it. Do it again.” In the creation of The B-Side, “we [Miller and Moeng] made the arrangement, the score, and then got into a room to rehearse, and things just transformed. We encouraged that. It was a collaboration between all of us.”

Philip Miller. Image: Malibongwe Tyilo

Artists in crisis

The point of The B-Side wasn’t only to remind South Africans of Caluza’s legacy, but also to help fund the accomplished and talented South African musicians that are alive and working today; a moment in history that has been especially devastating for performers.

The project owes its existence largely to the support of several funders, including the SAMRO Foundation, Nando’s, the Goethe-Institut, the Butler School of Music and the University of Texas in Austin.

“I thank our funders hugely because in this particular instance, it was really tough to get this project funded,” Miller relates, “because in this country there is no funding from the state… We have no government funding in the arts. We have a dysfunctional department of arts and culture, a dysfunctional national arts council. Over Covid, artists couldn’t survive.”

But a large amount of the credit should also go to the individuals who donated money (any amount) to the #musorelief fund that Miller initiated to fund the artists involved in the project (and to which you can still donate – the banking details are found on the fourth slide here). This money helps these musicians “literally to keep going”, says Miller, “so that they can pay their school fees for their kids and get food on the table”.

It also is an incentive to keep making and appreciating music. As Miller reminds us, “the scores are now available on the SAMRO website as PDFs for any musician to use.” The album is free to stream and is available to anyone who can get online.

“That was part of it – to let this out without a commercial imperative. It’s out there, and that was part of our mission… to get this music to everyone.” DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.