BOOK

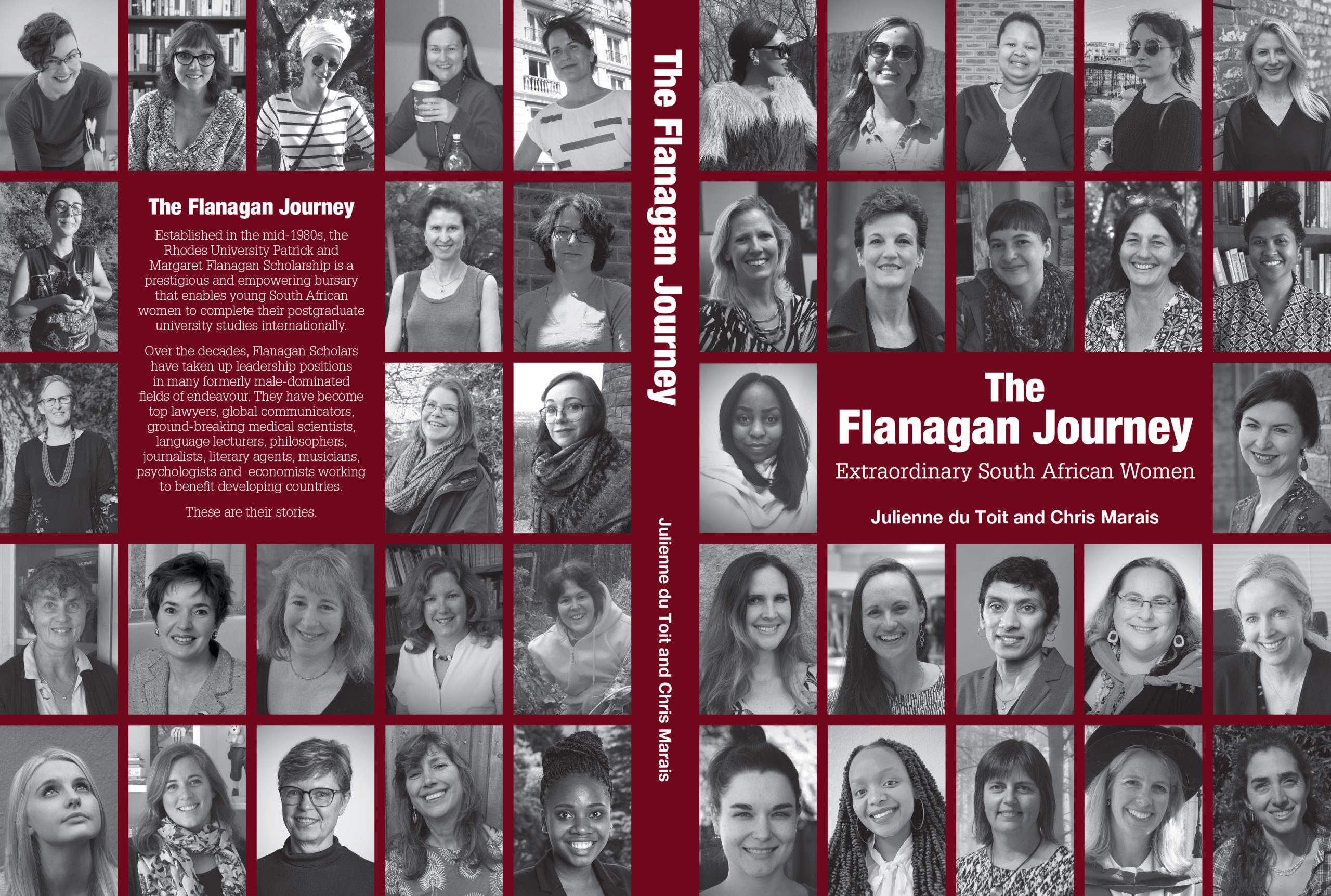

The Flanagan Journey: Extraordinary South African Women

A book about 45 remarkable South African women who studied overseas and made their mark on the world.

In late 2019, Rhodes University’s Research Office approached us to collaborate on a very unusual book.

What director Jaine Roberts and postgraduate funding manager John Gillam had in mind were the profiles of 46 women who had been awarded a scholarship between 1985 and 2020.

The Patrick and Margaret Flanagan Trust bursary was for women only, specifically those who wanted to do postgraduate studies at a major overseas university like Oxford, Cambridge or Edinburgh. Other than that, and being bright English-speaking academics, they had little in common.

The result is a book published by Rhodes University in mid-2021, The Flanagan Journey: Extraordinary South African Women.

These Flanagans, as we began to call them, had pursued studies in medicine, history, economics, musicology, business, various aspects of law, psychology, English literature, virology, plant genomics, statistics and physics.

They came from universities all over South Africa and went on to do their master’s or doctoral studies at institutions including Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, Cornell, St Andrews and the London School of Economics. Others had opted for Global South universities – Peking University in Beijing, the University of Dar es Salaam or the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, India.

Some had made a life for themselves overseas. Most had returned to South Africa.

Professor Ameena Goga, now a unit director at the SA Medical Research Council, was awarded the Flanagan in 1995. Image: Supplied

Asafika Mpako, now working at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, spent her 2017 Flanagan year doing her master’s in management science and public policy at the University of Peking in China. Image: Supplied

The Number One Flanagan Detective Agency

There was one big problem. Records were out of date, and alas, women often change their surnames when marrying.

We started with those who were straightforward to find, simply because they have fairly high profiles.

Locating Rebecca Davis of Daily Maverick and Yvonne Beyers, editor of Huisgenoot magazine, was trouble-free. So too Professor Ameena Goga of the SA Medical Research Council, who has come into prominence because of her work on HIV and Covid. Isobel Dixon, a well-known book agent representing many South African authors (including Deon Meyer) in London, was easy to contact.

No matter her profession, Dr Zosa de Sas Kropiwnicki-Gruber was always going to be a doddle, thanks to her distinctive name. Dr Thando Njovane was lecturing at Rhodes University, so contacting her was no problem either. Quite a few were still overseas studying, having gone on to doctorates or postdoctoral research fellowships. John Gillam could help us track them, usually via their families.

Cassidy Parker, the Flanagan awardee of 2008, went to do her master’s in English literature at the University of York, UK. Image: Supplied

Isobel Dixon, the Flanagan awardee of 1993, studied literature at the University of Edinburgh and is now head of books and MD of the Blake Friedmann Literary Agency in London. Image: Supplied

But some Flanagans seemed to have vanished without a trace. For weeks, sometimes months, we followed up leads, Googled like mad and still came up empty handed. Then we had a breakthrough, and another, and another and eventually we started calling ourselves the Number One Flanagan Detective Agency.

Carla Schier was one of the most elusive. She had done her master’s in environmental history at St Andrews University, came back and started work at The Citizen newspaper and then, after two years, apparently disappeared into thin air.

It turned out she had gone to America, studied and practised midwifery, and had then fallen under the spell of professional cake-making. She was living happily ever after in Seattle, having changed her surname twice.

One Flanagan, now on a farm in Portugal, had changed her first name and her sexual orientation. Pheiffer Sutherland was only found because we were complaining bitterly about this particular vanishing act to Simon Pamphilon, the book’s designer. He happened to have good friends in the linguistics department at Rhodes University, where this missing Flanagan had studied. He made some enquiries, we followed up on his lead, and voila, another Flanagan was in the bag. At which point Simon became an honorary branch officer of the Number One Flanagan Detective Agency.

In the end we tracked down 45 out of 46 of the Flanagans. One, Leanne Peiser, is still in the wind.

Professor Jennifer Scott, who studied political science at Oxford in 1987, is now at New York University’s Department of Corporate Communications and Public Relations.

Image: David Plakke

Nonjabulo Mlangeni, awardee of 2016, went to read for her Master of Arts in African American studies at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA).

Image: Supplied

Zooming and Skypeing

Chris and I managed to have face-to-face interviews with those living or working in Makhanda (Grahamstown) and Cape Town before Covid-19 locked down the country. Then, from April 2020, while everyone else was learning to bake sourdough bread and brew pineapple beer, we were having long and fascinating Skype and Zoom interviews with women living all over South Africa and overseas.

During these interviews and research into their fields, Chris and I gained insights into financial derivatives, the inner life of plants, night duty for paediatricians, the world of book agents, music therapy, developmental psychology, Zapatistas, speculative fiction, macroeconomics, the grammar of transgender, film studies, HIV activism, the weird world of viruses, the partition of Africa, collective self-deception, public health, public law, the Naxalite communists, the National Credit Act and the intriguing genre of black horror.

We also learnt about a phenomenon called the Impostor Syndrome, which beset many of these young academics. Development psychologist Dr Lauren Wild of the University of Cape Town (and one of the Flanagans) explained:

It’s the “voice that says ‘I don’t really belong here, they made a mistake’. As South Africans we have a tendency to put ourselves down and think we’re not as good as they are overseas.”

She added (as many did) that it was pleasant to discover that South African academics hold their own in international institutions.

Daily Maverick journalist Rebecca Davis did her MPhil in linguistics at Oxford University during her Flanagan year (2006). Image: Supplied

Dr Rebecca Hodes did her PhD in the history of medicine science and technology at the University of Oxford, and is renowned for her work in HIV/AIDS research and activism.

Image: Supplied

Highs and lows

We heard about the amazing breakthroughs, encounters, experiences, friendships and insights the Flanagans gained, all their highs and many of their lows. A few of these included living in shared or tiny quarters, episodes of loneliness, being homesick, feeling unsure.

Asafika Mpako, who used her Flanagan year to study at Peking University before being accepted at the London School of Economics, initially struggled to adjust to Chinese people constantly wanting pictures of her. She coped by turning the camera on them.

Cheree Olivier took a while to adjust to the cold and rain of the Netherlands, and found comfort in pancakes and chocolates while studying public international law at the University of Leiden. She dropped the weight when she returned.

Amy Langston headed off to study statistics at the University of Glasgow a few months before Covid-19 shuttered everything in 2020. She was cloistered away in shared accommodation and wrote her exams online before coming back and starting to lecture at Rhodes University.

Sally Hutton, the first woman to become managing partner at a major law firm (Webber Wentzel), used her Flanagan year to study legal research at Oxford. Image: Supplied

Yvonne Beyers, editor of Huisgenoot magazine, studied English literature at the University of Edinburgh during her Flanagan year in 2003. Image: Supplied

Thanks to Margaret Flanagan

The awardees told us how they grew academically and personally from their experiences. Many of the Flanagans mentioned how grateful they were to their benefactor, who had died in 1982, leaving a bequest to send young women overseas to study.

In her last will and testament, Margaret Flanagan wrote:

“My underlying intention in making provision for the award of scholarships is my belief that the future of any country is, to an important extent, dependent on the women of that country being educated.”

Jaine Roberts of Rhodes University’s Research Office sums up her legacy in the foreword:

The book “is a testament and tribute to the achievements of all the scholarship awardees and to what Margaret Flanagan’s bequest, carefully invested and managed by Rhodes University, has been able to support to date, and will continue to support in perpetuity”. DM/ML

This article first appeared on Karoo Space. If you are interested in getting a signed copy of The Flanagan Journey, email [email protected] for more details.

Flanagan book cover. Image: Supplied

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.