MAVERICK CITIZEN: NIDS-CRAM WAVE 5

The need to counter vaccine apartheid begins on home turf

President Cyril Ramaphosa recently called out Europe, the UK and the US about their so-called vaccine hoarding, claiming that this behaviour amounts to vaccine apartheid. However, what is the South African government doing about vaccine equity at home?

Ronelle Burger is a Professor in Economics and a researcher at the Research on Socio Economic Policy group. Vasti Roodt is an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy and the Head of the Unit for Social and Political Ethics in the Centre for Applied Ethics.

We can define the fairest allocation of vaccines as one that leads to the greatest reduction in harm for all citizens and not only the vaccinated. Reduction of harm is framed broadly to include both health consequences such as loss of life and social and economic consequences such as loss of livelihood.

In an imperfect world of supply and logistical constraints, we need to prioritise who gets vaccinated before whom. But how do we reconcile such prioritisation with fairness? By accepting the principle that vaccinating some ahead of others should not be at the cost of others. It would be unfair to expect some people to bear the full burden of continued exposure to harm merely so that others could benefit from vaccination.

Vaccinating the groups at greatest risk of dying and with the highest concentrations of cases will reduce hospitalisations and deaths. This, in turn, will ease the medical case for lockdowns. The social and economic impact of lockdown is devastating. The harsh first lockdown in April and May last year led to the loss of almost 3 million jobs, a rapid rise in hunger as well as increased reports of gender-based violence and mental health problems.

Paired with these moral concerns about the large consequences of prioritisation decisions are the practical worries about efficiency and logistics, given fiscal constraints and the likely need for ‘top-up’ vaccinations next year.

Nurses who are vaccinating are also no longer attending to their other duties and as a result, health services are likely to suffer. To maximise value and minimise cost, we must optimise the number of vaccinations per nurse per day.

A more rapid roll-out will also ensure that we reduce the waiting time for persons with mortality risk who are placed towards the back of the queue in the Phase II group. This in turn will reduce the scale and severity of the trade-offs between different prioritisation scenarios.

South Africa’s approach has been to prioritise healthcare workers in Phase I, followed by a Phase II that is set to prioritise persons of 60 years and older, essential workers, persons in congregate settings, teachers, and persons over 18 years with co-morbidities. Within the large Phase II group of over 16 million people, we have chosen to first vaccinate those over 60, then teachers, after that police officers with those 50 and over to follow by the middle of this month.

There is good reason to prioritise healthcare workers based on their vulnerability, exposure and, crucially, their frontline role in fighting the pandemic. They are responsible for the care of everyone else who falls sick.

Teachers’ prioritisation is based on a combination of exposure — which has become more pertinent with the early evidence that the Delta variant affects children significantly more than previous variants did — and the value of minimising learning losses and children dropping out of school.

We all have an interest in the care and education of the next generation, and this may be one of the most critical investments for our future, so it makes sense to prioritise teachers.

Older people are more likely to fall ill with Covid-19 and require hospitalisation. The rationale for age-based prioritisation is therefore a combination of mortality risk and safeguarding access to healthcare for everyone.

In each case, vaccination of the prioritised group does not solely carry benefits for those vaccinated. It also reduces the risk of harm for the as-yet unvaccinated.

In Gauteng and the Western Cape, the share of those 60 and over who have been vaccinated is three times higher for the insured, compared to the uninsured. In the country as a whole, it is twice as high.

This resonates with what we already know about our country: those with resources are better able to navigate bureaucratic systems. The relatively affluent can more easily register online. Their personal networks provide useful information and practical tips, while access to a car enables travel to outlying vaccination sites that may have excess capacity to allow walk-ins.

This has enabled the better resourced to beat the system and get vaccinated earlier, while others need to wait for their vaccination slot. And this can explain the faster vaccinates rates of the insured to date.

Yet the progress in vaccinating the affluent comes despite higher levels of vaccine reluctance and hesitancy amongst this group. The most recent wave of the Nids-Cram Survey shows that vaccine acceptance is significantly lower amongst respondents with characteristics that correlate with affluence, such as living in urban formal residential housing, having Afrikaans as a home language, and self-identifying as White.

Conversely, vaccine acceptance is higher amongst respondents living in traditional settlements, amongst isiZulu, isiTsonga and Setswana speakers, and amongst black respondents.

Those with the greatest trust in the state’s vaccine rollout are thus the very people who have been least served by it.

In our ambitious narrative about the country we aspire to be, it matters that we pursue equity not only in our stated priorities but also in the implementation of those priorities. We need a vaccine rollout strategy that is as equitable as possible and achievable.

We must make it easier for those with the fewest resources to access available vaccines.

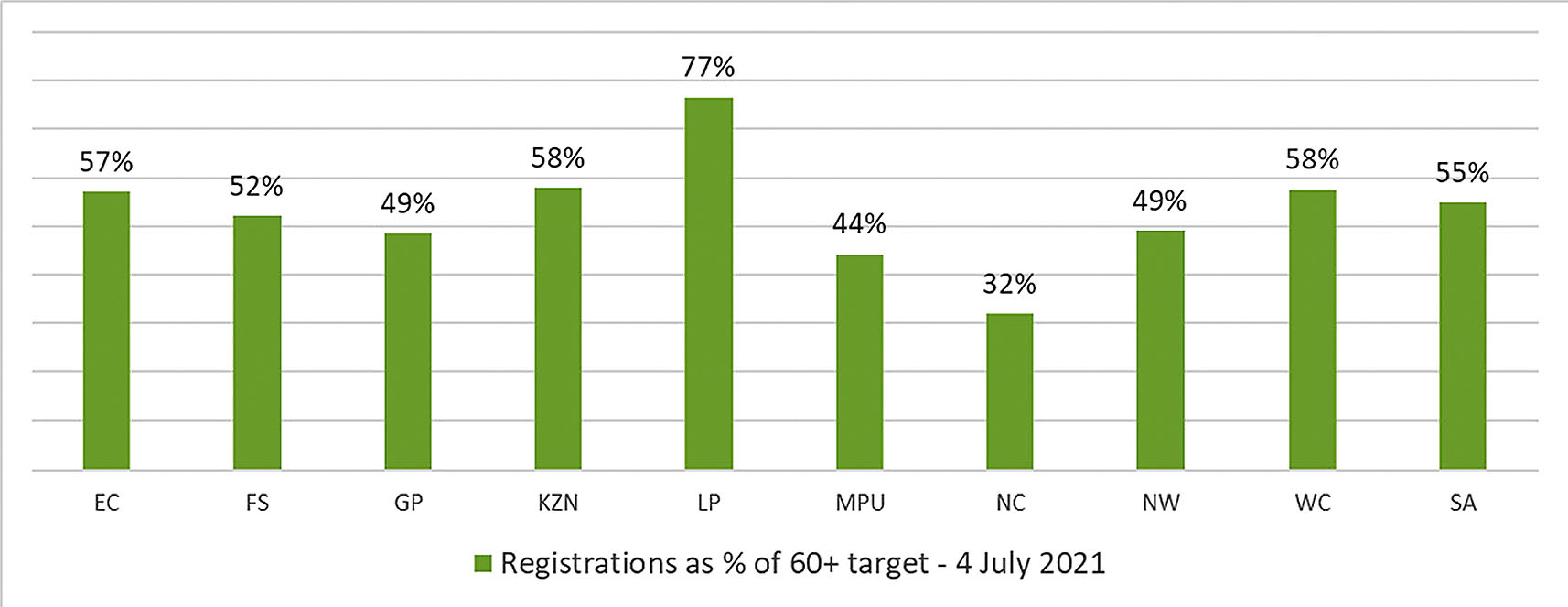

Fortunately, we have the case study of Limpopo’s vaccination campaign to guide this effort. South Africa’s poorest province is leading all other provinces — including richer provinces such as Gauteng and the Western Cape — in its rapid progress with registrations and vaccinations of the sixty and over group.

How did they do it? Given the province’s strong traditional and religious roots, they have chosen to first vaccinate prominent and trusted leaders including bishops and the Queen Mother of the Bapedi.

There is evidence for vaccinating community leaders early. The Nids-Cram survey shows that even among the staunchest opposers of vaccines, 38% say that they would be willing to get vaccinated if a trusted community leader was vaccinated and remained healthy.

Limpopo has also equipped its Community Health Workers with smartphones to enable door-to-door vaccine registrations of its high share of illiterate elderly. It also helps that they have vaccination sites in close proximity to communities.

More convenient ways of registering for vaccinations, and facilitating the spread of reliable local information about vaccines and vaccination centres, are vital for overcoming the obstacles that a lack of resources can create.

If we want to thwart vaccine apartheid at home, with future deaths of the pandemic being highly concentrated amongst the poorest South Africans, other provinces would do well to follow Limpopo’s lead.

We might complain about global vaccine distribution, but let us start in our own backyard. The poor are not accessing vaccines at the same rate as the wealthy. The consequences of that are both predictable and avoidable. DM/MC

Ronelle Burger is a Professor in Economics and a researcher at the Research on Socioeconomic Policy group. Vasti Roodt is an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy and the Head of the Unit for Social and Political Ethics in the Centre for Applied Ethics.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider