Maverick Life

Underwater otherworld: A dive into the Cape’s kelp forests

It’s an alien world right on our doorstep, in the frightfully frigid waters of the Atlantic. Keith Bain meets the world’s foremost ambassador for Cape Town’s kelp forests and discovers the reward for enduring that bracingly cold seawater.

Even with a wetsuit, it’s not my cup of tea. I’m a ninny from Durban so the mere thought of getting into the sea off the coast of Cape Town is triggering. Never mind spending prolonged periods voluntarily bobbing about the icy waters of False Bay, even if we’re to be snorkelling through the seaweed in search of living treasures.

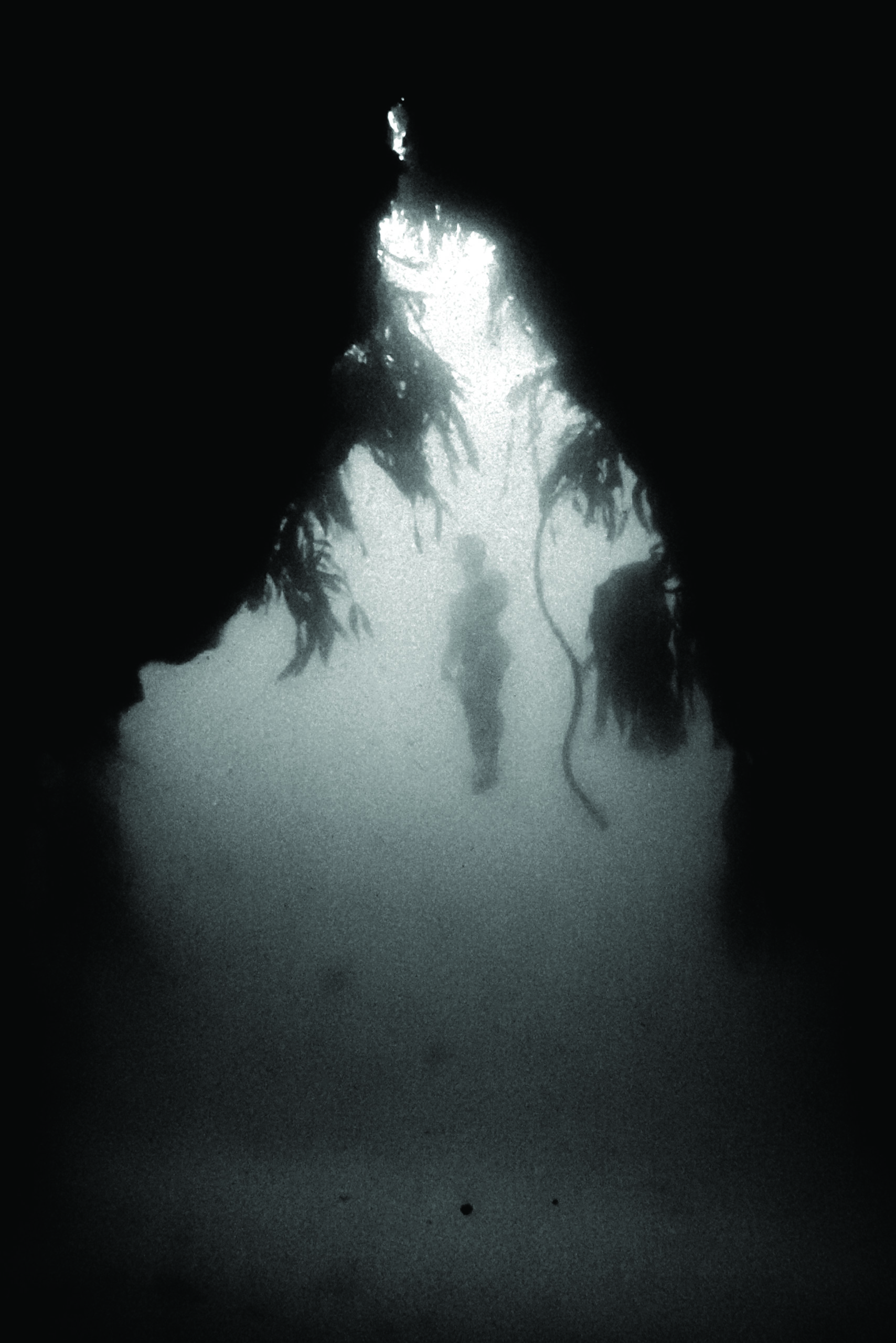

Underwater wonderland. Picture by Pippa Ehrlich.

Roger Horrocks filming in the seaforest on ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture by Pippa Ehrlich.

The most recent such expedition was in Simon’s Town, with the hardy crew from Shark Warrior Adventures. It was only the thrill of having penguins swim towards us that kept me in the Zen zone (“Just breathe,” a seasoned cold-water junkie had told me, “you need to stoke the cold fire within”). Still, I could feel a mild level of chill-induced panic working its way through my system.

But then there was the unbridled joy of finding humongous stingrays gliding below us like gently flapping flying saucers the size of VW Beetles. The kind of sighting that takes your breath away, makes you forget everything that ails you. Certainly, watching those majestic creatures put a pause on my physical discomfort.

Nevertheless, there came a point when my jaws were chattering uncontrollably as I lost the will to fight the sensation of freezing – this, despite the fact that the sun was shining brightly, and I was squished inside a wetsuit.

Like I said: a Durban ninny.

By contrast, there’s someone like Craig Foster. Not only Cape Town born and bred but raised near the water’s edge, in Bakoven, where the winter waves would pound against his family’s bungalow and he and his brother spent many happy days foraging in rock pools and being smashed against the boulders.

Craig Foster. Image courtesy of Sea of Change

As grown-ups, the brothers became award-winning documentary filmmakers, exposing themselves to incredible extremes to capture riveting episodes of life in Africa.

Eventually, after three hectic films about crocodiles, Foster reached a kind of burnout. He was tired, stretched beyond his limits, his body weak. That’s when his memory drew him back to the ocean. He felt its call, he says, a powerful desire to get into the sea just in front of his home in Simon’s Town, and swim with nature.

No ninny, Foster went in bare-skinned. “I don’t scuba dive. All I wear is a mask, fins, a hoodie because cold-water ear has set in, and a weight belt. No wetsuit. I go minimalist, with a small high-power, tucked-away camera. One breath of air and off we go.”

It sounds horrific, but spend an hour listening to Foster talk about his underwater adventures, and he’ll convince you to get in that water, too, coaxing you into the life-giving embrace of the cold Atlantic as though your life depends on it.

He says it took a year to adjust, physically, to the cold – going against everything your body tells you, complaining about the pain, overcoming the desire to get out. He forced himself to go back over and over again. After a year, he says the body starts to crave the cold.

Behind the scenes of ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture by Faine Loubser.

Diving. Picture courtesy of Sea Change Project

While Foster started going into the water for a personal reset, something else happened over the weeks, then months, and now about 10 years of daily – that’s correct: daily – dives. Not only was his vitality restored by the cold, but he found himself falling in love with the creatures he encountered in the water. “It’s paradise. I live on the edge of a vast wilderness, a golden forest filled with incredible animals, many unknown to science. Some tiny, some quite enormous.”

That “golden forest” is in fact a kelp forest, a vast aquatic ecosystem stretching from Cape Agulhas, at the southern tip of Africa, to central Namibia. Foster calls it the “Great African Sea Forest”. And it’s among the most productive ecosystems on Earth.

To the naïve, casual observer, though, kelp forests don’t look like much. From outside the water, they might seem like nothing more than tangles of oceanic weed, or dodgy, murky water, perhaps.

But that seaweed, comprising such giant kelp species as sea bamboo (Ecklonia maxima), split-fan kelp (Laminaria pallida) and bladder kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera), forms the foundation of an intricate food web, enabling an extensive variety of lifeforms to thrive. This abundance includes fish species like southern mullet, strepies and Hottentots that dwell permanently among the kelp as well as many more that move through it to look for food.

Kelp grows extremely fast – up to 13mm per day – and although requiring sunlight to photosynthesise, it doesn’t need roots to extract nutrients from the substrate, instead absorbing them directly from the water. They’re not plants, but algae, and what look like roots are actually a modified anchoring system called a “holdfast”.

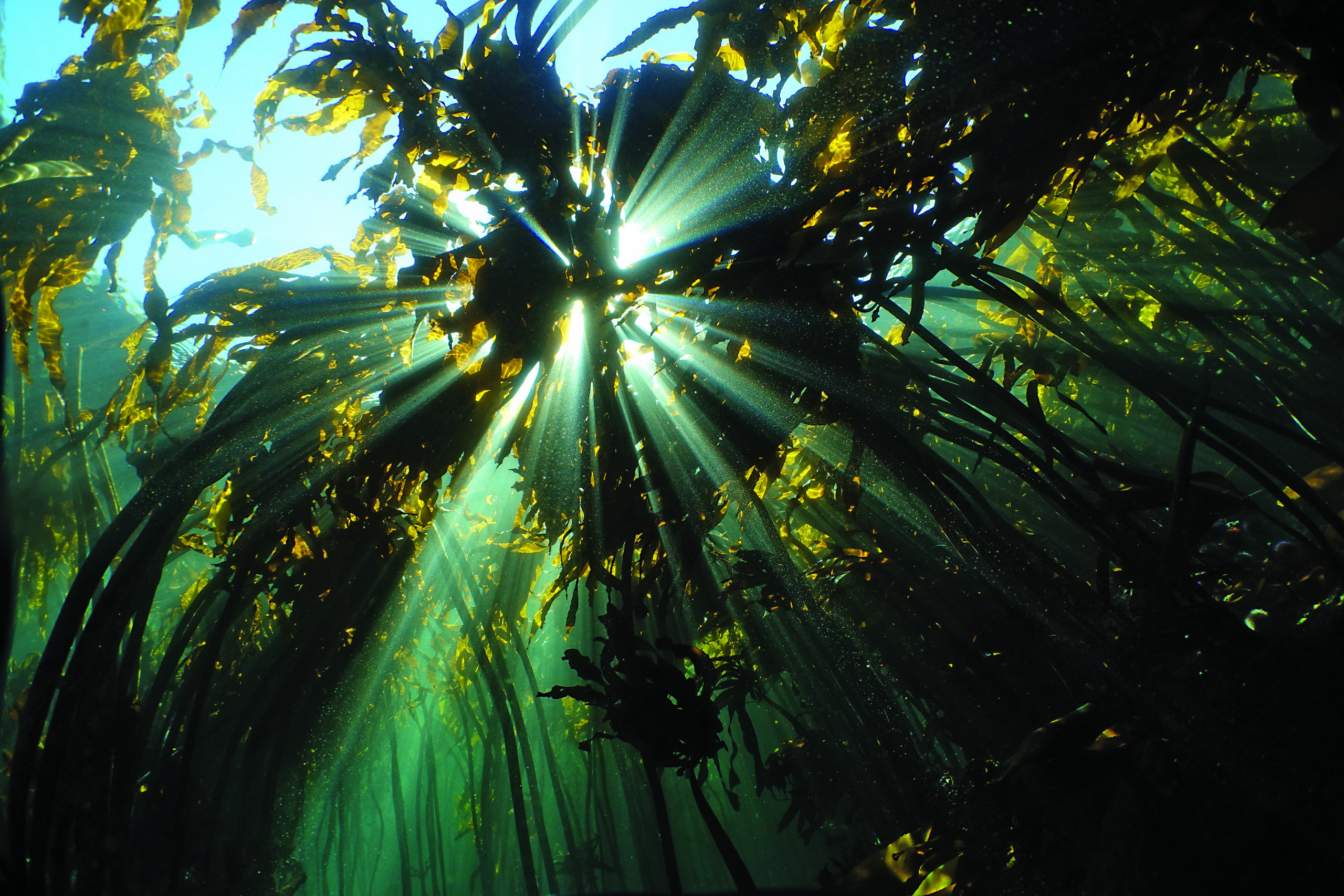

Up through the kelp forest. Picture by Craig Foster.

Kelp forest from below. Picture courtesy of Sea Change Project

Because they exist under water, it’s difficult to meaningfully explain the scale of these vast ecosystems; they seem to defy imagination. “If kelp forests were on land, we’d be utterly blown away by their magnitude,” says Jone Porter, education director at the South African Association for Marine Biological Research. “They’re massive, but because they’re in water they don’t need big, strong trunks the way trees do.” In other words, they operate in a manner that’s almost alien to us land-going humans; below the surface, it’s another world.

Dive in, as Foster does, and the scene is indeed otherworldly. The kelp – up to 30m tall – buoyantly dances as the current moves it side to side, so that there’s this incredible play of sunlight filtering down from above, streaming through the gaps almost hypnotically, the light glancing off the mirror-like silvery scales of fish that seem to fly through the canopy the way birds do in the arboreal world.

“Many of the animals are in the shallower waters, just five to 10m below,” says Foster, adding that some of these creatures make our most mind-blowing science fiction seem tame. It’s not just that these species are weird to look at, but might possess incredible shapeshifting abilities, or a seemingly supernatural talent for mimicking rock surfaces or wiggling into tiny crevices to evade predators. Their interpersonal dynamics, their daily struggles for survival are mind-blowing.

“Right in front of my house I can find the biggest stingray in the world – a 4[1/2]-metre creature that will come right up to me. They’re incredibly gentle as long as you don’t threaten them. Or I can be among huge numbers of sharks – packs up to 60-strong. From white sharks to cow sharks, spotted gully sharks to smaller catsharks.”

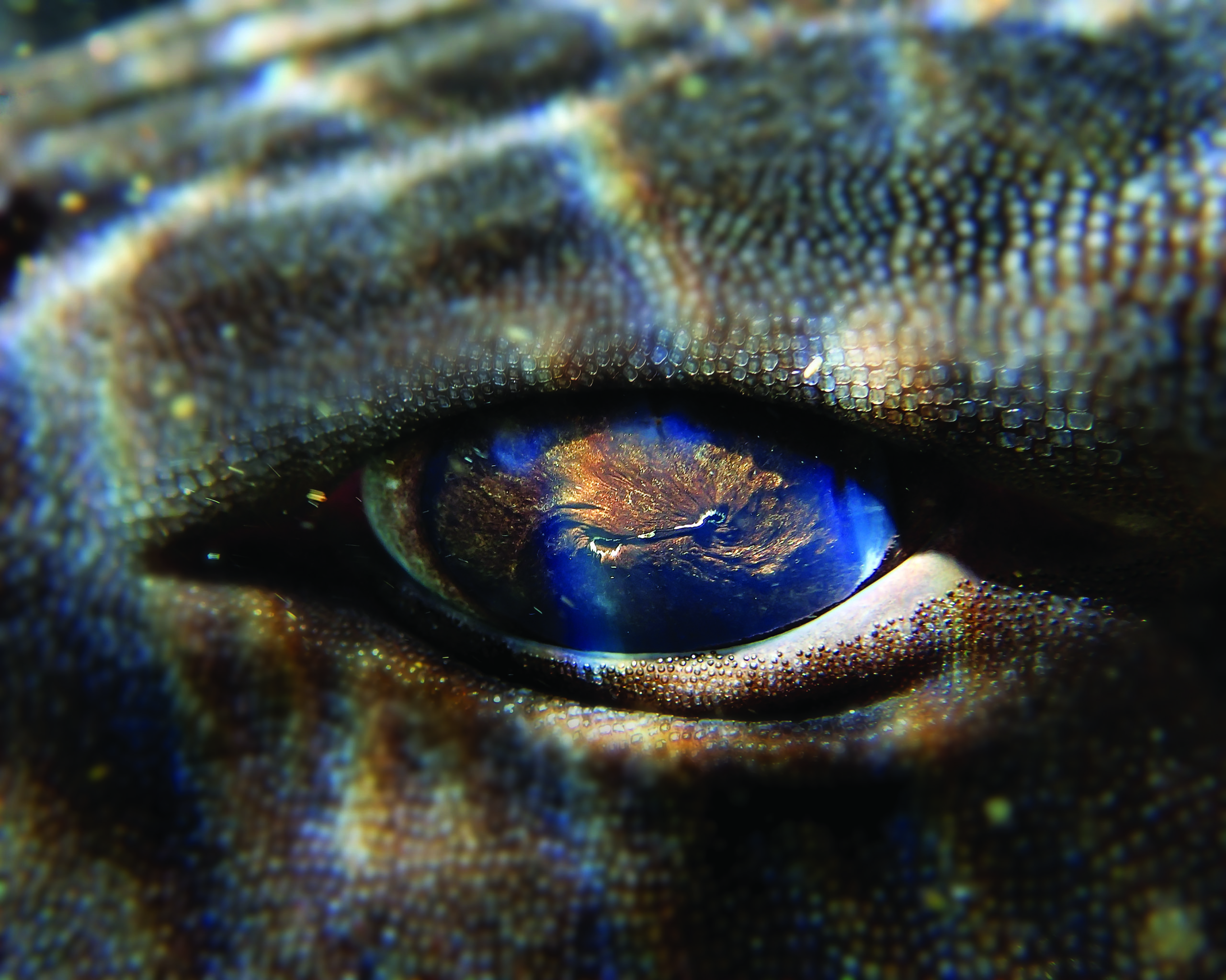

Close up of a catshark eye. Picture courtesy of Sea Change Project.

Photograph By Pippa Ehrlich, while filming ‘My Octopus Teacher’.

Picture by Craig Foster.

Glimpse closely into the eye of one of those pyjama catsharks, he says, and you witness something astonishing. Because it’s nocturnal, it collects aragonite (a crystal form of calcium carbonate) from the water and processes it to build a shiny mirror at the back of its eye. This enables it to gather even faint moonlight and navigate through the dark forest at night. It sees 10 times better than humans do in low light.

One animal everyone hopes to see in False Bay’s kelp forests is the seven-gill cow shark, among the most prehistoric shark species, recognisable by their seven gill slits – other sharks have five. Watching them feed in social packs is a highlight for divers.

Casual sightings are one thing, but as Foster’s decade-long interaction with the kelp forest suggests, it takes more than the odd visit to really get to know its inhabitants intimately. Foster’s perseverance has made him a serial discoverer of new species – he’s even had a shrimp, Heteromysis fosteri, named after him.

What’s heightened the magic of Foster’s dives is that the years spent in this environment have taught him to completely relax around animals, enabling them to more readily engage with him, demonstrating behaviours that will blow your mind.

He’s had a Cape clawless otter reach out to touch his face, a catshark lie in his outstretched hands, and one of those enormous stingrays wrap its wings around him. Which is, as you can imagine, potentially very scary.

“I’m not particularly brave,” he says. “But I’m not scared of great whites; because I’m used to them. I’ve slowly been introduced to small sharks and then bigger and bigger ones over the years. I know what to do, and I know that they probably won’t kill me. I know what to do if they try. It’s not bravery.”

Picture by Craig Foster.

Octopus. Photographs by picture by Craig Foster.

Octopus. Photographs by picture by Craig Foster.

Octopus walking on two legs. Picture courtesy of Sea Change Project

Octopus using shells as protection or defense. Courtesy of Sea Change Project

A blue dragon – or sea swallow. Picture courtesy of Sea Change Project.

Urchin eating. Picture courtesy of Sea Change Project

It was one shy creature’s bravery, though, that has perhaps most deeply touched Foster’s soul. Some of the most memorable times he’s spent in the sea have been with a common octopus he befriended after she literally reached out to him, overcoming her instinctive fear. The two formed an unprecedented bond that became the subject of a documentary that caused a worldwide stir in 2020 when it was dropped on Netflix.

The film shows how, over the course of a year, Foster was able to document this octopus displaying a vast repertoire of astonishing behaviours, from walking along the bottom of the sea using two arms as though bipedal, to literally playing with fish, and using shells to instantaneously create a defensive shield.

The film is by now known to just about anyone with a pulse and an interest in wildlife; it has not only racked up awards at festivals around the world but is among the nominees for an Oscar in the documentary feature category. It’s quite an accomplishment given the intimacy of the filmmaking, not to mention the complexity of the human-animal interaction that happens in front of the camera.

It is as if humans had managed to make contact with an alien life form – and overcome the vast gaps of understanding such a meeting might conceivably entail. It’s thanks to the level of trust that Foster forges with this octopus that the film becomes one of those rare cinematic events when a reality that’s revealed seems somehow more imaginative, dreamed up or unreal than most fictional films.

Pippa Ehrlich. Director of ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture courtesy of Sea Change Project

While filming ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture by Craig Foster, courtesy of Sea Change Project

While filming ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture by Craig Foster, courtesy of Sea Change Project

While filming ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture by Craig Foster, courtesy of Sea Change Project

While filming ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture by Craig Foster, courtesy of Sea Change Project

Behind the scenes of ‘My Octopus Teacher’. Picture by Faine Loubser.

Some of it is barely believable. And yet that’s the point of the film: To reveal this mysterious animal’s incredible intelligence and demonstrate why her habitat – the kelp forest – is worth saving.

Even if, like me, you’re a ninny with an intense dislike of the cold, the promise of seeing such wonders does tend to make up for the immediate physical discomfort of getting into those frigid waters. And, if not, the cold will only make you stronger, apparently.

“There’s a Master Switch that gets flipped,” says Foster. “The cold has healing powers. It changes the hormonal functioning of the body. There’s a total transformation, a rush of hormones all the time to the brain.”

And if not, so what? Once you’ve dipped into this alien world what’s going to leave a lasting impression is not the shivering, but the extraordinary abundance of life. And the countless implausible miracles that are happening, ceaselessly, between the gigantic strands of algae that form this precious forest beneath the sea. DM/ML

Few have done as much to spread the word about the African kelp forest as Craig Foster who established the Sea Change Project, a collective of journalists, filmmakers, divers, naturalists and scientists seeking to bring awareness to this important and vulnerable ecosystem. Their hope is that it will be declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, affording it better protection from ongoing threats such as overfishing and pollution. Their work includes Sea Change – Primal Joy and the Art of Underwater Tracking (Quivertree Publications), a book featuring 336 pages of astonishing images and a captivating story documenting an eight-year collaboration between Foster and Ross Frylinck, a surfer and free-diver who joined him on his kelp forest explorations. Few things will soften your heart, though, as much as My Octopus Teacher, the Oscar-nominated Netflix documentary detailing Foster’s relationship with a common octopus he befriended during his kelp forest dives. seachangeproject.com

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Beautiful. Free!

What an amazing story and what an amazing human: Craig Foster.

What a beautiful account of the octopus.

Get ready for the Oscar!!