“I remember this one time, I was trying to go into Arts on Main for a meeting. At the time I was carrying a China bag, because it’s safer to carry in Joburg… I could put my phones and laptop and money in there. People won’t pay you any mind because they don’t think you have anything valuable in it,” says 43-year-old artist Senzeni Mthwakazi Marasela, recounting an incident in Johannesburg’s Maboneng Precinct, at the Arts on Main hub of studios, galleries, workshops and eateries.

“The security guard said to me: ‘Sorry, auntie, you can’t come in, no hawkers.’ I was taken aback a bit. I’d only been wearing the dress for a couple of months, and I think in my head it had become like a second skin, so at that moment I wasn’t thinking about the implications of entering spaces in Joburg in that dress.”

The dress is made from the ubiquitous Shweshwe fabric that has been woven over time into culturally significant clothing in different parts of South Africa, such as when it is worn by newlywed women in Xhosa culture. At the turn of the century some designers incorporated it into their collections, making it “trendy”. Yet, it remains mostly tied to specific cultural events or practices, and worn by older women in rural areas.

Marasela would wear that dress with a “doek” on her head, sometimes with the checked China bag. She wore it – one of 21 identical dresses she made – every day as part of a durational performance that lasted six years, from 2013 to 2019.

The dresses Marasela wore as part of her six-year-long performance, now hanging at Zeitz MOCCA. Photo courtesy of the museum

The dresses are hanging at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (MOCAA) in Cape Town, as part of Waiting for Gebane (18 December 2020 – 02 May 2021), an exhibition covering nearly two decades of her practice. It started in 2003, when she first embarked on a project, Theodorah comes to Johannesburg, inspired by her mother Theodorah’s stories of travelling there in her youth.

“My mother had this habit of wearing dresses obsessively and then discarding them. So in 2003 I decided to take one of her dresses, a yellow dress. I wore it and I went to the places she and my father remembered having been – I tried to retrace their steps as part of that project to create work about Theodorah’s experiences in Joburg.”

Theodorah Comes To Johannesburg, 2004, Photographic series. Courtesy of the artist

Theodorah Comes To Johannesburg, 2004, Photographic series. Courtesy of the artist

Theodorah Comes To Johannesburg, 2004, Photographic series. Courtesy of the artist

Theodorah Comes To Johannesburg, 2004, Photographic series. Courtesy of the artist

Theodorah Comes to Johannesburg 12, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

Marasela’s work embodies not only her parents’ experiences, but those of her aunts and many other black women who travelled to the city from villages and townships.

The Theodorah in Marasela’s art went there in search of her husband after many years of waiting – symbolic of the journeys of many South African women – the wives, sisters, mothers and girlfriends of migrant workers, or those who waited for imprisoned fathers, brothers, and uncles during the apartheid years.

“I think it was at Wits… that I chose to work with fabric [and] it continues to be the material of my choice,” says Marasela, who graduated from the University of Witwatersrand in 1998.

“There was a project that I did using heirlooms, things people inherited from their mothers, things you find in a kist when you get married or a family tablecloth that has been passed down through generations. It was about looking at how attitudes about people that occupied space and memories are also transported through domestic objects, intimate objects as well.

“And then I realised that fabric or things that we wear are historical documents because they carry so much information. We remember what we were wearing at certain events, we make an effort to wear something to certain events. There’s largely a particular reason we have for putting something on.”

Indeed, her dresses – as they hang at the museum, supported by her photographic documentation, watercolour paintings and embroidered textiles – carry the story of her experiences over the six years she wore them. Each of them reflects something about our society; our ideas of who is allowed where, and the pressure to assimilate or be ostracised.

- Theodorah Carrying the World 2019 Red cotton thread embroidery on house linen. Courtesy of the artist

- Theodorah Carrying the World 2019 Red cotton thread embroidery on house linen. Courtesy of the artist

- Theodorah Carrying the World 2019 Red cotton thread embroidery on house linen. Courtesy of the artist

- Theodorah Carrying the World 2019 Red cotton thread embroidery on house linen. Courtesy of the artist

Eventually, she made it into Arts on Main when the person she was supposed to meet came down and explained to the guard and apologised to Marasela. “I thought, ‘this is terrible’; it means that there are people who don’t get access to spaces because they look a particular way. It disturbed me for weeks,” she says.

Not long after she had another experience when visiting an office in Sandton for a work-related meeting. “I was sitting in the reception area and I was the only person there. And the person I was supposed to meet came out and kept on saying, ‘we’re waiting for Senzeni’, even though I had told them I was there already.” Later, when she confronted the person about the incident, they told her they thought she was “someone visiting one of the workers”.

Then there was an incident at a party in Camps Bay, Cape Town, where she was asked to go and wash dishes by someone who assumed she worked there.

Her experiences of being profiled in the dress aren’t limited to South Africa. “I was in New York, Venice, Amsterdam, Greece; I became this freak as I travelled. I think Africans in those spaces assimilate through clothing first, and then they learn the language. And then me dressed as Theodorah, I stood out like a sore thumb,” says Senzeni.

In New York, she was held up at the airport because they thought she was a refugee. Her luggage was searched and she had to explain why all her dresses were the same. “They wanted to know if I was trying to sell things. The only thing that saved me was going on my social media and showing them my page. Then they apologised and let me through.”

In Italy, thinking they were being charitable, some people tried to give her food, assuming she was a refugee. In Greece, they found her to be “exotic”.

Perhaps one of the most revealing experiences in terms of the role clothes play in ideas of assimilation and belonging, was with her family.

While it wasn’t a big deal when she wore her mother’s yellow dress as part of a limited performance and photographic documentation in 2003, the experience took its toll on them when she embarked on the six-year performance in 2013 as Theodora, in the red dress.

“I began to notice when cousins my age wanted to take photographs [at family events], they would move away from me, as if me being in the picture would ruin the photographs, because they’re all dolled up. I also noticed they would often ask me to take the photograph.”

After two years of not being invited to be part of family pictures, she decided to buy her own camera with a self-timer, so she could be.

“Initially, my parents were frustrated by the performance. My mother thought that, like I had done with the first dress, that I would wear it when I needed to work then I would take it off. I remember there was a time when my father offered to give me money to go and buy clothes. I think in the last year of the performance, he kind of relented… he left me alone. I think in year five and six he totally stopped complaining, there was just this acceptance. One time I caught him explaining my dress to all the relatives, that I am an artist and this is what I’m trying to do, and this is my life’s work. Now, my mother explains it because she’s seen and she’s understood what I do. She explains what I do much better. Even though she was so frustrated by the dress. But I had to work quite hard to be part of the family memories, as Senzeni as well, to be able to have these photographs and say I was there at so and so’s wedding, I was there when the family gathered. Otherwise, I would not be there if I didn’t have that self-timer.”

The pictures and the family moments they capture reflect not only the difference in clothing between Marasela’s Theodorah and her family, but very real moments, and at times a certain tension that speaks to the discomfort of family members around Theodorah and the kind of person her attire represents.

While for many in her professional and family life the dress became a barrier to entry, in other places it became a shield and a sort of invisibility cloak.

“I source so much stuff from downtown Johannesburg. And typically before I go I have to spend the night before thinking about what I need to carry so I don’t get mugged, what I need to wear so that I don’t get assaulted. Going out to Joburg for me as a woman can’t just be a random decision, I need to plan it. I can’t stand out, I need to disappear in the crowd and not draw attention to myself. It’s extremely traumatic, you know. There are women who have told me that when they go to work in the morning they have to carry sharp scissors and knives, to arm themselves just in case. In a way, the dress gave me a lot of protection, and I would get these men complimenting how ‘decent’ I look.

“One has a lot of difficulty trying to understand why being in the city centre should be so brutal for black women, why even the edges of the shops are occupied by these aggressive men who are out to police the behaviour of women and what they wear,” says Marasela.

In the last 18 months of her six-year performance, she got tattoos on her arms, and once again people changed the way they interacted with her. “Before that, in public places, people totally ignored me. Then when I got the tattoos, people would just come and talk to me, even in the malls. They’d say: ‘Hello auntie, where did you get your tattoos? Why do you have tattoos?’ One woman even asked if I got them in jail.

“I became something totally different with tattoos on my arms, something hip; the dress was now seen as rebellious. Before the tattoos people would try and speak Pidgin English, like Fanagolo, to me at parties, like I wouldn’t understand English. But with the tattoos suddenly they spoke to me in normal English, as though the tattoos meant that I understood English. I was quite amazed.”

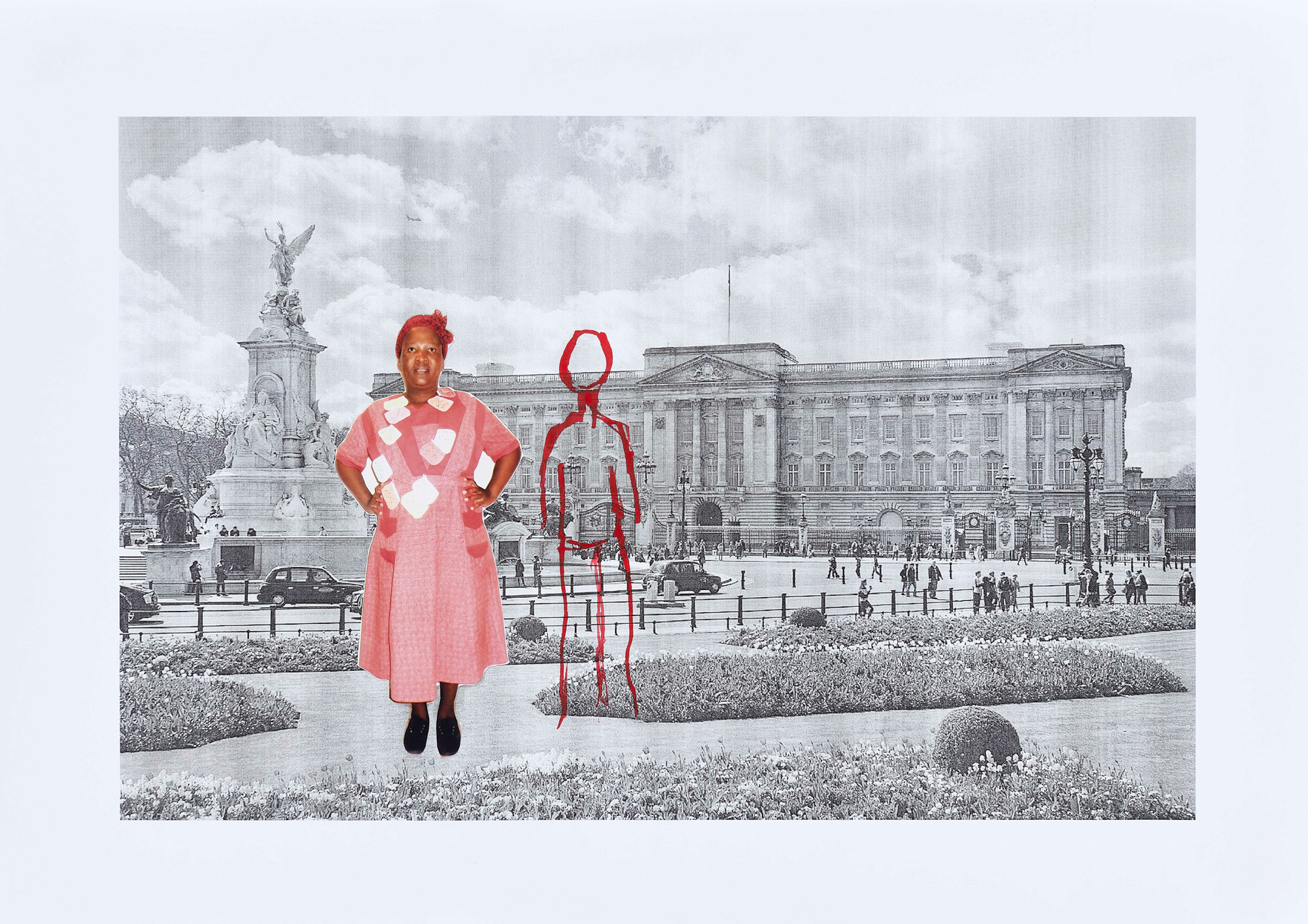

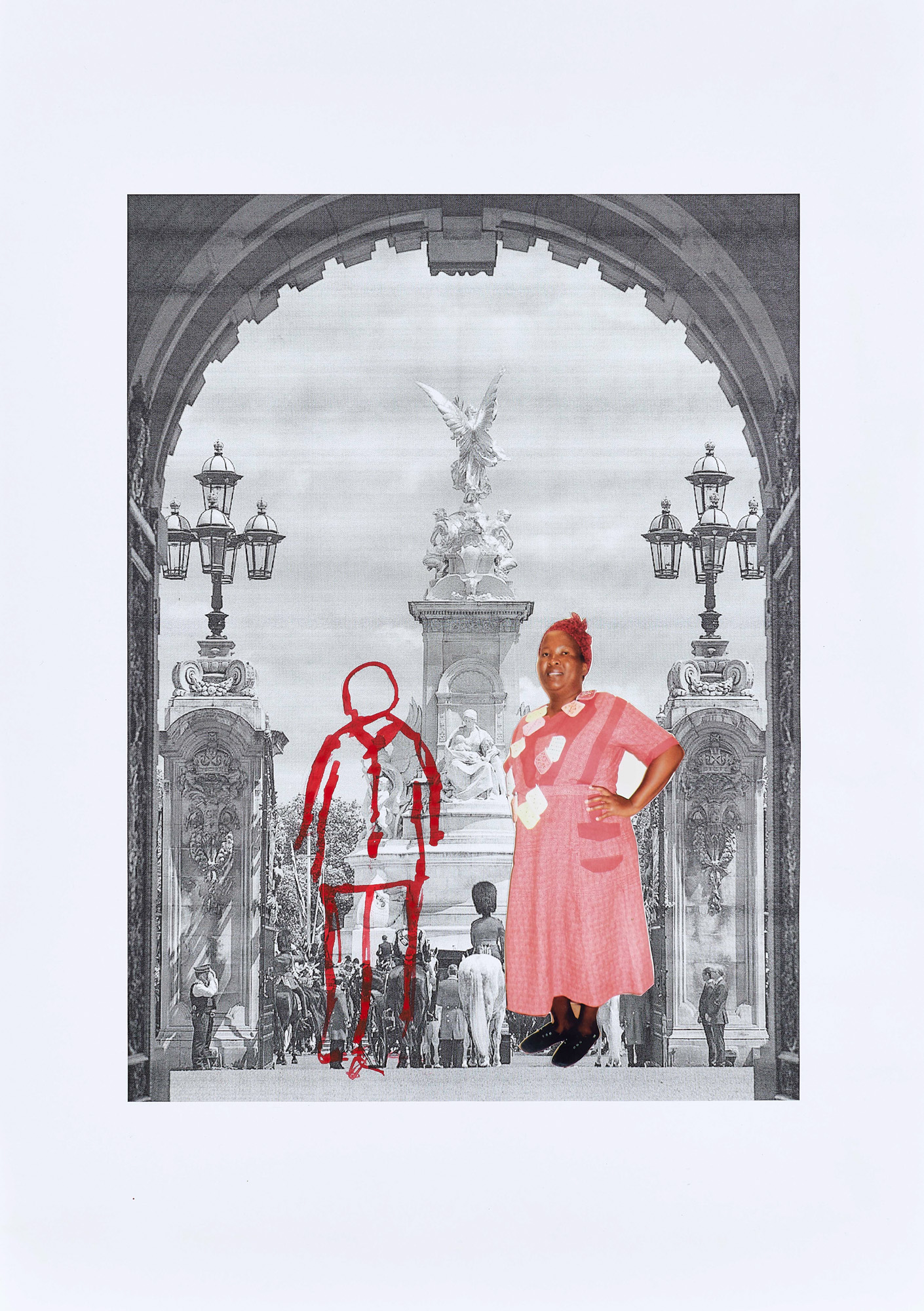

Back at the Zeitz-MOCAA, in one section of Marasela’s exhibition, hang a series of collage-style photographs that make up a body of work titled, in isiZulu, Izithombe zendawo esizithandayo” (“pictures of our favourite places”). In each photograph the image of Theodorah in her red dress is pasted over a pixelated black-and-white image of a touristy destination, from the Taj Mahal and Dubai, to safaris, Victoria falls and Buckingham Palace. Next to her in each one is a rough, almost childlike drawing of Theodorah’s husband, Gebane.

Izithombe Zendawo Esizithandayo 2, 2017. Photomontage and pen on photocopy. Courtesy of the artist.

Izithombe Zendawo Esizithandayo 2, 2017, Photomontage and pen on photocopy. Courtesy of the artist.

Izithombe Zendawo Esizithandayo 2, 2017 Photomontage and pen on photocopy. Courtesy of the artist.

Izithombe Zendawo Esizithandayo 2, 2017, Photomontage and pen on photocopy. Courtesy of the artist.

Izithombe Zendawo Esizithandayo 2, 2017, Photomontage and pen on photocopy. Courtesy of the artist.

In these images – inspired in part by the photo studios of the 80s where Johannesburgers would have pictures taken against backgrounds of dreamy locales and send them to their faraway families – Theodorah dreams of the holidays she and Gebane will go on one day. Besides the juxtaposition of her red dress and the pixelated background, the image invites the viewer to confront their own prejudices. When one imagines a globetrotting holidaymaker, what do they look like? What are they wearing? Does Theodorah’s dress belong? If not, why not?

Now that she is done with her daily performance of Theodorah, Marasela has no plan to wear the dress again in daily life. But she is continuing the work with Theodorah, exploring her transformation into a “city girl”.

“I also had a lot of struggles that I didn’t anticipate, because I was wearing what I thought was a common dress. I didn’t anticipate how much I would have to explain myself in spaces, be it buildings, or work… Sometimes when I think about the way I was treated, I think it was so… so silently brutal, you know, when you are dismissed up until you feel so out of place. From people assuming that because I look that way I must be the hired help, to harassment at borders when I was trying to travel, to being in Joburg and witnessing other women being violated because they look a particular way, to being spoken to in a particular way. It also raises questions about my own body, and how one can protect it in a way, and the idea that it is mine and I own it. How much of it do I own?” says Marasela. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Amazing story. It shows how we treat people based on our first look at them and our assumptions flowing from it.

Wow ! And most of us still think we do not prejudge people based on appearance. Insightful and revelatory.

Just extraordinary – thank you!