ART

The tricolour bag that came to symbolise migration

Cheap, practical and easily accessible, the red, blue white and check bag has become an apt symbol for migration in 21st-century art.

“The names given to those bags are often derogatory words to describe the immigrant demographic. They’re known as Ghana Must Go bags in Nigeria, after the Ghanaians were expelled there; in Germany, they’re called Tuekenkoffer, which is a Turkish or Polish suitcase, named after the immigrant demographic you find there.

“In the Caribbean, they’re called Guyanese Samsonite, in England they’re known as Bangladeshi bags, in New York as Chinatown totes, and in the Limpopo here in South Africa they’re known as Zimbabwe bags,” explains artist Dan Halter, referring to the ubiquitous red, white and blue check nylon bags which he started incorporating into his artworks in 2008, after the wave of xenophobic attacks in South Africa.

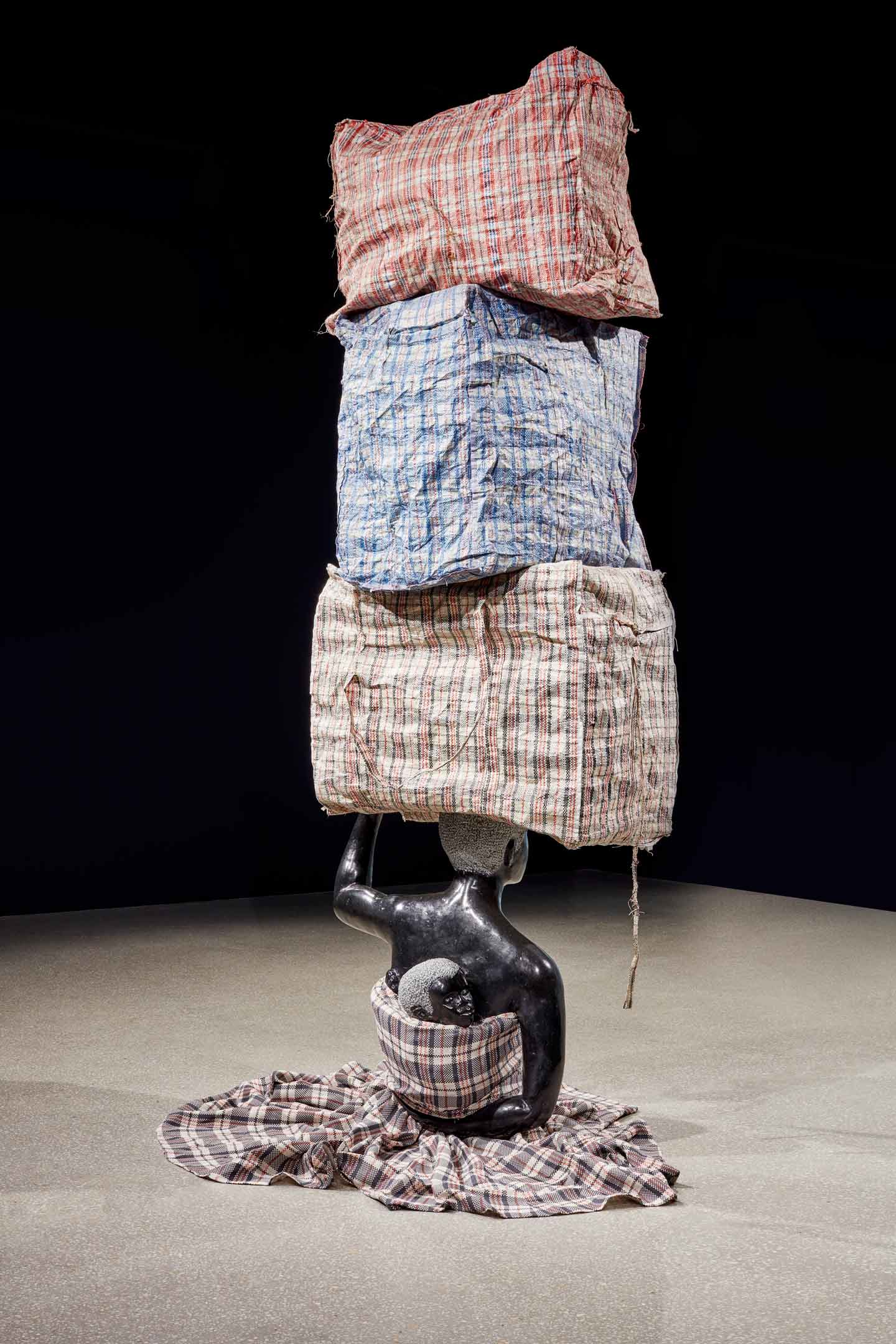

MAI MABAG (BACK), 2019, Dan Halter. Used plastic weave bags and wireframes, Black Serpentine. 110 x 122 x 240 cm. Stone carving by FARO. Wirework by Kuda Kuimba. Pattern making and stitching by Sibongile Tete. Photograph by Hayden Phipps

Once again, the bags form a large part of his current exhibition, ‘Cross the River in a Crowd’, which is on at WHATIFTHEWORLD gallery in Cape Town until 31 August 2019.

Just shy of 3km from Halter’s solo show, at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA), artist Nobukho Nqaba’s exhibition opened on 1 August, and will run until 20 October 2019. Titled “Izicwangciso Zezethu…” (We Make Plans), the exhibition is housed in one of the museum’s permanent collection galleries. Here, the walls, the floor and the furniture in the room are all covered in the check fabric.

Installation shot of Nobukho Nqaba’s exhibition at the Zeitz MOCAA. Photograph: Twitter/ZeitzMocaa

Nqaba has been using the bags in her work since 2011.

“It’s a bag that was used a lot in my upbringing, by my family during our travels from the Eastern Cape to Cape Town. It’s also a bag that symbolises struggle and poverty because it’s cheap and easily acquirable, although nowadays it’s used as a fashion accessory and other things.

“But, for me it’s significant because it’s a symbol of migration and movement within the country,” says Nqaba. In her work, the bag is referred to by its colloquial Xhosa term, “uMaskhenkethe”, which translates to “the traveller”, but can also be read as “let’s travel”.

Umaskhenkethe Likhaya Lam, 2015. Photograph by Nobukho Nqaba

Nqaba’s exhibition considers the concept of home as a transient space.

“I decided to deconstruct the bag a little and paste it on to the walls. I wanted to bring about that sense of home as I knew it when we grew up in the shacks, where people would cover the interior of the shack with posters and branded papers,” she explains, referring to a practice which performed the dual function of insulation and decoration.

“Instead of using newspapers, I decided to use these bags because I wanted to bring back that idea of a shack not being a permanent structure. There’s always a fear or danger that you will lose it at some point, whether because the government chases you away, or a fire. It also speaks about global migration and how people interpret the concept of home; it’s not something that’s always there, especially if you consider what’s happening currently in Europe.

Photograph by Nobukho Nqaba

“It’s about investigating that whole idea of a home being always in transit, especially to the migrant worker, to that person who’s always looking for greener pastures.”

Although the fabric was made in Taiwan, it gained popularity in its current incarnation as a bag in 1960s Hong Kong as a cheap carry-all bag. There, also popular in its striped version, its affordability and utility have made it synonymous with 1960s working-class Hong Kong.

In 2001, Hong Kong designer and artist Stanley Wong began incorporating the red white and blue bag into his work. In 2004, when he curated an exhibition for the Hong Kong Heritage Museum titled “Building Hong Kong”, he invited artists and designers to interpret the material for the exhibition.

Installation shot of Stanley Wong’s collaboration with Hermès, 2013. Photograph courtesy of Hermès.

In the preface to the exhibition catalogue, his view of the bag takes on a more nostalgic and patriotic angle of its role in Hong Kong society: “These could be sheets at construction sites, the canopies outside street-side groceries. Or it might take the form of baggage carrying our belongings, our presents to take back home to villages on visits, even our dreams. The omnipresent plastic sheet soon acquired its own character, complete with attitudes, not unlike a human being standing steadfastly by his post, patiently facing life’s difficulties, and struggling on without a word of complaint – to be involved in our own city. This is very much like Hong Kong people of the 1960 and 1970s….I hope the starting point of this exhibition, is to take the redwhiteblue (sic) to express [the] positive spirit of Hong Kong.”

Wong too has covered entire rooms in the fabric, one of the most well-known being a collaboration with luxury fashion brand Hermès in 2013, where he also included the Union Jack as well as the US flag, embracing the international appeal of the bag. Other major fashion brands have also used the bag’s appeal by creating high-end runway versions; two well-known instances being Louis Vuitton’s Spring 2007 patent leather, and Balenciaga’s 2016 bag.

Fashion’s sporadic fascination aside, the cheaper non-designer version of the bag continues to serve practical purposes across the world. Like Nqaba, whose personal history is intertwined with the bag, so are the lived experiences of many traders, migrants, and working-class people. It is those histories that Halter also seeks to incorporate into his artwork:

Installation view from Dan Halter’s exhibition, Cross the river in a crowd. Photograph by Hayden Phipps

“I buy the bags in bulk and then I go to markets like Greenmarket Square in Cape Town and Marabastad in Pretoria, and I ask if people can swap me old used bags for my new bags. They have a pattern of travel in them. Those are more interesting for me. I don’t treat them at all, they’re often very dirty and falling apart. I’m actually very interested in how they’ve been mended,” he explains, referring to the bags that end up as part of his artworks.

His exhibition takes its title from the Madagascan proverb, “Cross the river in a crowd and the crocodile won’t eat you.” Halter is well aware of how the work relates to current affairs: “At the moment, to get out of Zimbabwe is particularly difficult, the government is not issuing travel documents, they’re delaying it as long as possible. So, yes, the work does play into that, but I don’t exactly react to current events. At the end of the day, I am telling my story.”

Installation view from Dan Halter’s exhibition, Cross the river in a crowd. Photograph by Hayden Phipps

Migration is something he knows about: “My parents were Swiss immigrants; my mother was born in Zimbabwe, so we didn’t have very deep roots there, but when I left Zimbabwe to go live in Switzerland at age 18, it was a culture shock. I was very homesick, and so I then came to Cape Town to study art. So yeah, I’m a little bit from everywhere. I’m a bit of an immigrant. My parents were attacked in Zimbabwe and they left the country, so I feel like they’re more the exiled ones in a way, not me.”

Looking back at history it can be argued that the human story is the story of migration, and not always out of choice. In the more recent human history that includes border crossing, but it can also be migration within countries. The latter informs much of the way Nqaba thinks about migration, having been born in eGcuwa (Butterworth) in the Eastern Cape.

“I started moving around at an early age, in 1996, when I would visit my mother who lived in the farmlands in Grabouw. The following year, in 1997, I started school in the Eastern Cape, and during the school holidays I would visit my mother; by 1999 I went to live with her permanently at the farm.” Due to limited space at the farm, Nqaba and her mother left and went to live in a shack. “Once again I had to be in a new school and be around new people.”

Three years later, she left the shack in Grabouw and moved to Khayelitsha, with a friend of her mother’s, leaving her mother behind. Her mother died that same year.

“I had to get accustomed to a new community, a new way of speaking, a new way of dressing because I was that child who had not had much exposure, I was always that rural girl who didn’t know much. When I left Khayelitsha to live in the suburbs, you could say that was yet another form of migration, because again you have to learn a new way of living. Even when you get to tertiary, it’s mental migration because you have to adopt a new way of thinking. So, migration happens both physically and mentally.”

As part of her exhibition, next to the single bed covered in the check, there is a Bible, also covered, open to Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd…”). Here it is even clearer to which kind of migrant, which kind of migration she is referring to in the work.

“To poor people, to the struggling, the Bible is something of great value; I speak from experience. People are always seeking after a source of hope and comfort, even if they are aware that their situation won’t get better, or maybe it will take time for things to get better. They need to remind themselves to remain strong, and church is their source of comfort,” Nqaba explains.

Psalm 23 was one of the most-read scriptures in her home when she was growing up. Her mother was a regular churchgoer, and although her dad didn’t attend as often, he prayed every night.

“Psalm 23 is etched in my mind, because it’s comforting. When you read it over and over again, sometimes it makes sense. Sometimes it sounds contradictory when you read that sentence: ‘I will fear no evil for You are with me’, and yet you find evil always follows you and you keep asking yourself, ‘Where is this person that’s meant to be watching over me?’” ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider