As the South African government stares down a debt-to-GDP ratio of close to 100% five years down the line, it will be sorely tempting to consider using financial repression to surmount this debt mountain when the time comes. Developed economies, with debt-to-GDP ratios upwards of 100% as a result of Covid stimulus packages, have already begun to head down this track.

The other option open to government’s with heavy debt burdens is to opt for the much tougher path of fiscal austerity and structural reform that the South African government has chosen to pursue. Globally, this alternative in a particularly politically and economically charged environment would likely prove unpalatable and greeted with widespread protests.

Financial repression is a combination of policy choices that enable the government to keep government borrowing costs artificially low. It provides a way out where the ultimate costs (higher inflation and slower growth) are not immediately apparent. Intereconomics, in a paper titled “Beware of Financial Repression: Lessons from History”, sums up these two choices: “Fiscal austerity makes unpopular decisions necessary. There are some obvious losers. Inflation, on the other hand, creeps up and is, therefore, less noticeable.”

Policy choices that facilitate financial repression include measures to increase demand for government debt, such as quantitative easing and capital controls and imposing interest rate ceilings to keep the cost of government debt under control.

For many developed economies, where some $16 trillion of fixed income assets are already trading at negative interest rates, financial repression is well underway. JP Morgan estimates that stock of sovereign debt trading at negative real (after inflation) interest rates amounts to $31 trillion – some 75% of outstanding government debt and up from just under 60% three years ago. The global bank also quantifies the extent of the monetary policy response to the pandemic shock: net rate cuts of more than 8 000 basis points and balance sheets expanding in major economies by more than $6 trillion.

The bias for central banks remains accommodative and possibly on track for continued incremental easing, it says, pointing out that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand is likely to take interest rates into negative territory early next year, as is the Bank of England. Other major central banks are expected to engage in further quantitative easing.

At the same time, further fiscal stimulus packages are likely, with developed economies possibly requiring further fiscal support in response to the lockdown measures that are being put in place in an attempt to curb the exponential increase in COVID cases currently underway in Europe, the US and the UK.

Together these policy measures would make an even more compelling argument for engaging in financial repression. That’s not good for a world in which globalisation and multilateral cooperation is already under attack and where opting to inflate our way out of debt would be just another shift away from the financial liberalisation that has mostly served the world economy well for the past four decades.

The post-war decades provide a vivid case study of the consequences of artificially reducing government debt burdens using financial repression. Historically these measures have resulted in inflation and lower growth, as well as introducing economic distortions that are difficult to reverse and imposing other concerning socio-economic costs.

The people who ultimately bear the cost of financial repression are savers (trillions of negative-yielding fixed income assets act are a significant disincentive to save), the poor (1% of the world’s richest investors benefit from flourishing equity markets) and the private sector (governments crowd out companies’ ability to source credit at reasonable rates and zombie companies are kept alive at the expense of healthy companies).

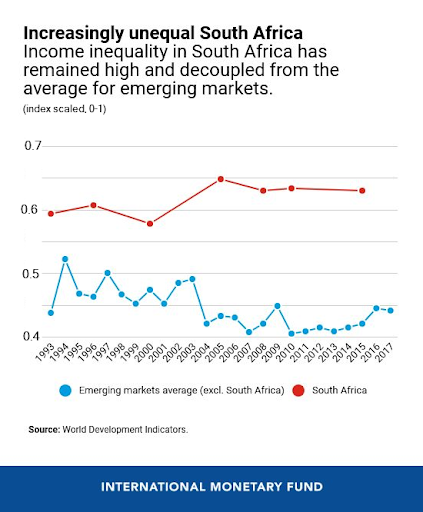

South Africa could ill afford these costs. Our savings rate is one of the lowest in the world (10.7% in the second quarter of this year versus a world average of 25.1% according to Stats SA), inequality is far higher than the emerging market average (see graph below) and the private sector has been out in the cold for the past decade during which public sector corruption has resulted in an economy that has been dominated by the public sector and, as a result, has generated suboptimal growth rates.

The Medium Term Budget Statement, delivered this week, is a painful refresher of challenges government faces in addressing its onerous fiscal burden and the associated threat of a debt crisis if National Treasury doesn’t take convincing action in managing its debt burden in the years to come (see Tim Cohen’s article yesterday).

Within an emerging market perspective, South Africa’s fiscal position doesn’t look so bad from a primary balance perspective, where, as the MTBS shows, it is middle of the pack. But more pertinent is that the country is projected to experience the largest increase in debt-to-GDP over the next three years (see graph below from the MTBPS presentation).

For now, however, the government shows few signs of giving in to the temptation of using financial repression as a means to get over its debt mountain. Quantitative easing has been negligible, there have been no official attempts to reduce high real interest rates on government debt, which currently are considered to adequately reflect the fiscal risk, and, so far, prescribed assets, which have been toyed with for years, haven’t made it onto the menu of policy alternatives.

In the MTBS, the government again spells out a way forward that ticks all the boxes of pursuing real structural reform that is less likely to stimulate inflation and more likely to put the economy on a sustainable growth track. But as Chris Holdsworth, Investec’s chief investment strategist, pointed out ahead of the mini-budget: “South Africa is rife with good plans. The problem is implementation and at this point, it is not sufficient to make the right noises, we need to see evidence of delivery.”

Thus the hard-hitting MTBS fiscal roadmap presented this week will remain a wish list until we see signs of concrete progress in respect of planned R300 billion non-interest expenditure cuts over the next three fiscal years and implementation of infrastructure private-public sector partnerships spelt out in the President’s Economic Recovery Plan. BM/DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Eskom still needs R250B to become a going concern. (Where from?)