OP-ED

Unleashing the power of pension funds and debt cancellation to finance a just energy transition (Part 4)

Three international energy research organisations have worked with Eskom trade unions to compile a report – ‘Eskom Transformed: Achieving a Just Energy Transition for South Africa’ – released on 23 July. This is the final piece of a four-part series on the analysis contained in the report, as well as proposed strategies for SA’s energy sector. The researchers argue that the future of an unbundled Eskom includes a multitude of problems.

“Debt cannot be repaid, first because if we don’t repay, the lenders won’t die. That is for sure. But if we repay, we are going to die. That is also for sure.”

Those were the words of the revolutionary former president of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara. Taken from his speech to the OAU in 1987, months before his assassination, his words are as true now as they were then. And especially so when locating the issue of debt in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic and the massive socioeconomic impact of the lockdown.

The issue of debt must also be situated within the overarching context of the need to finance a transition from a fossil-fuel economy to a low-carbon economy in the struggle to mitigate against the deep impacts of the ecological crisis. Repaying government debts, especially debts incurred against the interest of the majority of the population, leaves less money to invest in the rollout of renewable energy and the genuine, just transition that South Africa needs.

The issue of South Africa’s debt permeates throughout. The situation at state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the government’s increasing debt-to-GDP ratio is of serious concern. In response, the government, led by the Treasury, has prioritised debt-service costs at the expense of higher levels of social spending. As a result, debt-service costs are the fastest-growing budget item in the national budget.

Despite prioritising debt payments, South Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio has continued to grow and is likely to exceed 80% by the end of the year, rising from the February 2020 Budget estimate of 65.6%. At the end of the first quarter of 2020, South Africa’s gross external debt – what lies behind the growing debt-to-GDP ratio – stood at just over $155-billion. While an improvement since December 2019, with a decrease of $30-billion, further interrogation of SA debt is needed.

South Africa’s debt problems are strongly intertwined with Eskom’s growing financial woes. Eskom’s debt is expected to jump from R450-billion (in 2019) to at least R500-billion by the end of 2020.

Most reports link Eskom’s rising debt to the increased prevalence of corruption. This is an important factor, but it is not the only factor. Other considerations include: the increasing commercialisation and corporatisation of Eskom; the original high costs of the renewable energy independent power producer procurement programme (REIPPPP) contracts and the related 20-year power-purchase agreements; as well as the rapid increase in the cost of coal. These factors are detailed in the recently launched research report, Eskom Transformed.

It is undeniable that corruption and wasteful expenditure are major problems. Reports indicate that the Special Investigating Unit (SIU) is investigating the theft of tens of billions of rands from Eskom. Included in this are payments to the value of R139-billion in contracts related to the building of Medupi, Kusile and/or Ingula power stations.

An insider estimates that the cost of corruption in relation to Eskom’s contracts could potentially be as high as R500-billion. A seemingly clear-cut example of corruption relates to the World Bank loan to Medupi in 2010. Eskom is still repaying this loan: in fact, more than R1.3-billion was paid during the months of lockdown and, based on Alternative Information and Development Centre’s (AIDC) calculations, Eskom will only repay the debt in full by the end of the century.

That the loan was granted to build the biggest coal-fired power (read carbon-emitting) station in South Africa – contradicting the outcomes of the World Banks’ own research that indicates climate change has negative consequences for development – coupled with the fact that the loans seem to be infested with corruption, makes this a quintessential case of odious debt. There have already been calls for this debt to be cancelled, by the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU), AIDC, Public Affairs Research Institute and Daily Maverick’s Kevin Bloom, among others.

Given the scale of corruption, a publicly disclosed forensic audit of all SOE and government debt – with the intention to repudiate the odious debt – is necessary. This is in line with the demands made by Sankara more than three decades ago, and the more recent calls by more than 200 global organisations for debt cancellation following the outbreak of Covid-19.

Such an agreed debt cancellation would immediately create much needed fiscal room for enhanced social spending and public investment.

Notwithstanding the need for debt cancellation, it is important to recognise that a high government debt-to-GDP ratio is not inherently a problem. For instance, the UK (80.7%), France (98.1%), Belgium (98.6%), USA (107%), Singapore (126%) and Japan (237%), all maintain rather high government debt-to-GDP ratios.

The bigger question relates to a country’s ability to service those debts: for example, an economy that is experiencing rapid levels of growth is able to service debt costs easier than a country in an economic recession. Furthermore, when GDP is growing, it also reduces the overall debt-to-GDP ratio. Therefore, rather than focusing solely on the level of debt, a good debt policy is one that borrows to invest in improving a country’s productive capacity. Historically, this has proven to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio in the medium to long term. Conversely, fiscal consolidation in order to prioritise debt-service costs has often resulted in exactly that which it was meant to avert – a higher debt-to-GDP ratio.

Break the chains of dependency

Besides borrowing to invest in improving the country’s productive capacity, another aspect to consider relates to the level of domestic debt compared to debt denominated in foreign currency. Prioritising borrowing domestically should be preferential even if interest rates from foreign creditors are lower than domestic bonds, because borrowing from foreign creditors requires paying back in foreign currency. Financial inflows are needed for this purpose.

This requires higher interest rates which lead to higher interest payments (and dividends) paid to non-resident bondholders, which inevitably creates a vicious cycle of dependency on export-oriented growth and high interest rates to attract further financial inflows.

South Africa’s dependence on financial inflows to boost the financial account, and in so doing offsetting the current account deficit in the balance-of-payments, is a significant contributor to the country’s growing gross external debt.

Around 70% of the $30-billion decrease in SA’s gross external debt from December 2019 to March 2020 relates to falling general government liabilities to non-resident bondholders (from $78-billion to $56-billion). In other words, of the 16% decrease in the country’s gross external debt, 11% pertains to fewer liabilities owed to non-resident bondholders after a considerable decline in the foreign ownership of domestic bonds (to an eight-year low). This, following the sale of close to R100-billion in domestic bonds by non-resident bondholders in the first quarter of the year.

Introducing more stringent capital controls could both reduce the level of outflows and alleviate the pressure on the current account by limiting the amount (and delaying the time) of dividends and interests paid to non-resident bondholders.

While a small share (10%) of government debt is foreign-denominated debt as a percentage of its total debt, approximately 50% of SOE’s debt is held by foreign creditors. A good debt policy for both SOEs and government would be to prioritise borrowing from domestic creditors over foreign creditors. This brings us to the second major potential financial resource – pension funds.

The power of pension funds

Increasingly the power of pension funds is being understood. In 2002, Robin Blackburn in Banking on Death or Investing in Life points out:

“While a good pension regime could help to reinforce a healthy and sustainable pattern of economy, a bad and short-sighted one will compound economic dangers and social distempers.”

As financial capital became increasingly dominant within the global economy during the 1980s, investments shifted from productive capital in the real economy to greater levels of investment in stock markets, derivatives and speculative markets. With this, we see the intensified commodification and, in some instances, even privatisation of public goods such as electricity, water, health, housing and transport.

These essential goods and services are increasingly produced for profit maximisation rather than meeting people’s needs. Pension funds, public and private, are massive contributors to this trend.

Addiction to equity and the shackles of finance capital

South African pensions have amassed more than R4-trillion in accumulated reserves, making it one of the largest pension systems in the world. Much of this is invested in the JSE.

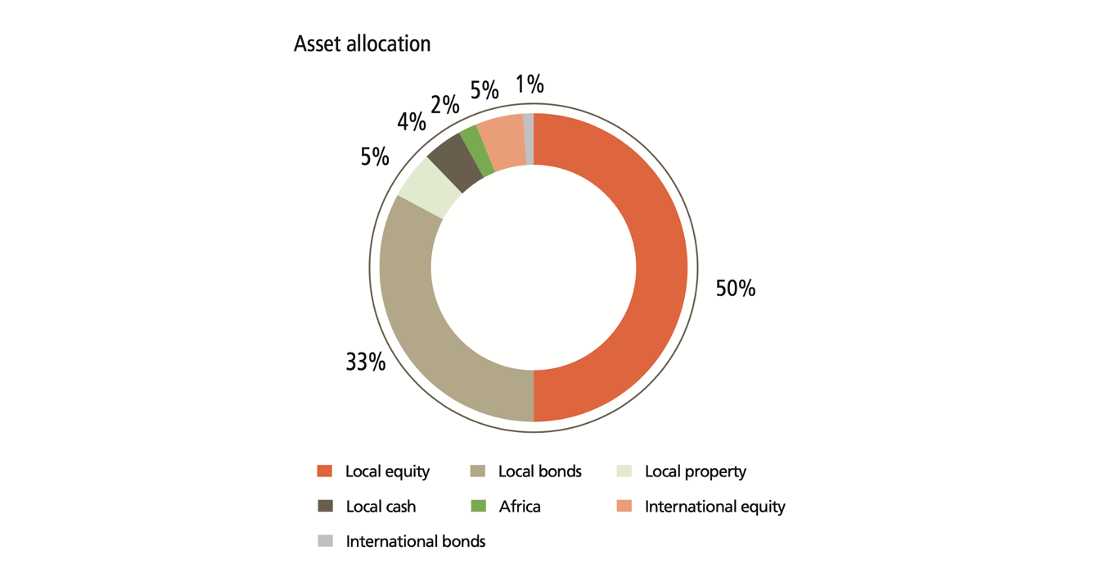

For example, more than half of all the Public Investment Corporation’s (PIC) R2-trillion in assets under management is invested in the JSE. The largest contributor to the PIC’s assets is the Government Employees’ Pension Fund (GEPF). Currently, the GEPF has approximately R1.8-trillion in accumulated reserves: two-thirds of this, just over R1-trillion is invested in the JSE.

Source: GEPF 2018/19 Annual Report

The GEPF’s investment strategy and its fixation on financial investments is exactly the kind of bad and short-sighted pension regime that Blackburn was referring to. The GEPFs overinvestment in the JSE as a result of the PIC’s addiction to equity has come at a huge price – the cost of growing unemployment and income inequality – due to the lack of investment in an industrialising, job-creating strategy. This process, coupled with declining labour share as a percentage of gross value added (i.e. falling real incomes), has meant that it is only through credit that households are able to make ends meet.

Liberate the GEPF

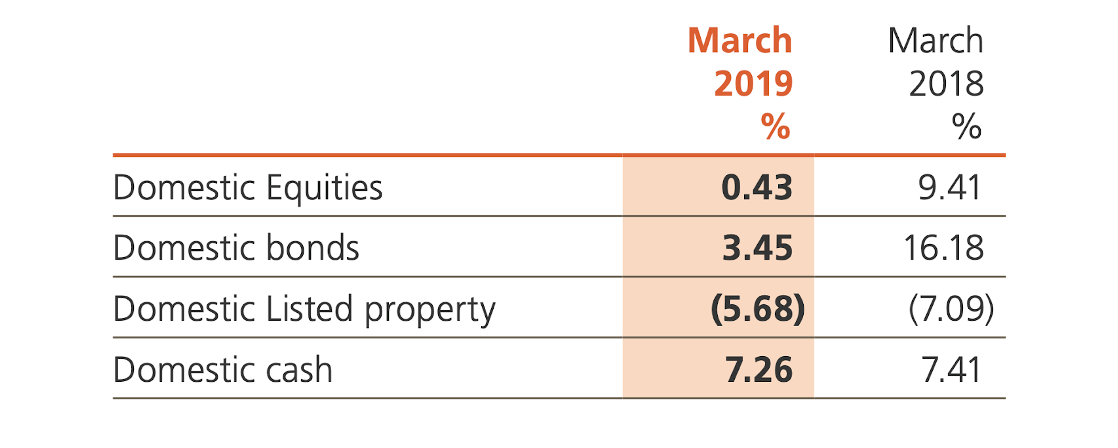

A shift in investment strategy to a greater share of investment in bonds rather than in equity is what is needed by the more than 1.7 million people – 1,265,000 public employees and 464,000 pensioners – who are directly dependent on the fund.

Moreover, the majority of South Africans who indirectly suffer, given the negative socioeconomic impacts of austerity-based macroeconomic policies, also stand to benefit from such a change in investment strategy. This shift will have a number of advantages, including the potential room to invest in the development of socially owned renewable energy, as well as stable and positive returns on investment.

Source: GEPF 2018/19 Annual Report

Back to a pay-as-you-go scheme

The amount of resources available is dependent on whether there is a continuation of the GEPF as a fully funded scheme, or if it shifts back to a pay-as-you-go scheme.

The growth of the fund is partly due to the transition in the fund from a pay-as-you-go scheme to a fully funded scheme. This transformation culminated with the amalgamation of various public pension funds with the GEPF’s establishment in 1996. The reasons behind this shift and its implications have been elaborated on before.

Prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, the GEPF was estimated to be 108% funded, and probably remains at approximately these levels in spite of the initial fall in the JSE. Under the GEPF law (1996), the fund can be 90% funded. There is also a view that credit rating agencies consider public pension funds finances to be healthy if they have more than 80% of their liabilities covered.

Reducing the GEPF’s funding level to 90% would liberate more than R300-billion for investment, while remaining within the confines of the GEPF law. It is possible to go further and liberate an additional R200-billion by reducing the level of funding to 80% of its total liabilities.

If the fund is transformed back into a pay-as-you-go scheme, more than R1-trillion in resources can be made available for investing in sustainable low-carbon, labour-intensive industries in driving a low-carbon reindustrialisation programme.

As we have previously mapped out, this has the potential to create a number of jobs in the development of renewable energy infrastructure manufacturing and the transformation of Eskom into a fully public renewable energy utility. But a just transition must be more than the development of renewable energy: it should also be about the development of a mass public housing programme, the improvement of the public transport system in urban and rural communities, as well as financing the transformation of our agrarian system from large-scale industrial farming to small-scale agro-ecology.

In addition to mitigating against carbon emissions, these developments are also labour and employment intensive – both directly and in downstream industries – and therefore they have large employment potential.

This is a major advantage for the GEPF in the medium to long term, and a necessity if it shifts back to a pay-as-you-go scheme. As Blackburn pointed out, this potential pool of finance that pension funds present to governments strikes fear into financiers and private investors (Banking on death, or investing in life, p74).

This may explain why some investors are dead set against utilising the GEPF in this way, as it may set a precedent that soon would require private pension funds to invest in domestic bonds as well. The Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) has already indicated that it would be in favour of reviving similar policy measures.

Make the Energy Intensive Users Group (EIUG) pay

Finally, in addition to the cancellation of government debts and liberating large levels of investment from the GEPF towards financing a just transition, it is also important to shift the pay structure of energy consumption and, in doing so, force disproportionately high-level electricity users to pay their fair share.

This includes not only the high level household consumers, but also those corporations and SOEs which form part of SA’s energy-intensive users group (EIUG). As electricity tariffs increase – approximately by 400% over the last decade – South African household consumers pay more in order to effectively subsidise the cheap electricity costs afforded to these 28 corporations. Almost half of the EIUG comes from mining and quarrying – major contributors to SA carbon emissions and increasingly employing fewer and fewer workers as the industry becomes increasingly capital intensive.

The current electricity tariff structure should be evaluated and more reasonable tariffs should be paid by intensive energy users, particularly major corporations.

Only the public can save us

In the February 2020 Budget, the finance minister said the Department of Public Enterprises’ (DPE’s) Eskom Roadmap is non-negotiable, opening the path for the unbundling of Eskom and the greater privatisation of the SA electricity sector. This is reminiscent of the way former finance minister Trevor Manuel introduced GEAR in 1996.

Emboldened by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni, Eskom CEO Andre de Ruyter recently indicated that the Eskom board intends expediting this process. As we have shown in previous articles, unbundling will not solve Eskom’s problems, nor will it help to catalyse a renewable energy transition – only a public pathway to a renewable energy transition can meet the challenge of climate change.

The resources to finance the transition are available, but to harness those resources requires us to rethink our understanding of the role of the economy. This necessitates shifting the thinking from what is financially affordable, to how we raise the finances required to meet the needs of our people and the planet.

This struggle over the economy is at the heart of the struggle to meet the challenges of climate change and the ecological crisis. DM

See also PART 1: Eskom unbundled: Contradictions in the plan will exacerbate the energy crisis, PART 2: Renewable energy must become a public good and PART 3: Only a public pathway for electricity supply can meet the climate crisis challenge

Dominic Brown is economic justice programme manager at the Alternative Information & Development Centre (AIDC). AIDC was part of the Eskom Research Reference Group which released a new report on 23 July entitled Eskom Transformed: Achieving a Just Energy Transition for South Africa, arguing that rather than unbundling and privatisation, Eskom’s transformation requires intensive decorporatisation.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider