PHILIPPI HORTICULTURAL AREA

Our Oasis: Living on the edge of urban encroachment

Activists won a landmark court battle in February 2020, stopping developers from paving over close to 500 hectares of the Philippi Horticultural Area. But other parts of the contested farmland are still under threat from land speculation. Before the ruling, Daily Maverick visited the area and spoke to subsistence farmers who have faced a decade-long struggle against urban encroachment. They fear development will disrupt the delicate ecosystem and signal an end to their way of life.

For years, the Philippi Horticultural Area (PHA) has been a battle zone. The farmland, roughly 20 minutes from the Cape Town city centre, has consistently been eyed as an area for housing developments and other land speculation. But farmers and other interest groups have opposed urban encroachment to protect the PHA, which is located on the Cape Flats Aquifer, a vital source of groundwater which makes year-round farming possible.

See special feature package: Cape of Storms to come

Within that battle zone are farming communities ranging from subsistence to commercial farmers who benefit from the arable land.

Recently, activist group the Philippi Food and Farming Campaign won a huge victory against the City and developers after a “precedent-setting” court judgment stopped pending construction on Oakland City, a mixed-use development. The court found that the City of Cape Town and provincial government did not consider the environmental impact that development would have in the area.

For the past 10 years, the campaign, backed by 33 civil society organisations, has been in and out of court fighting to save the shrinking farmland, despite being accused of being “anti-development”.

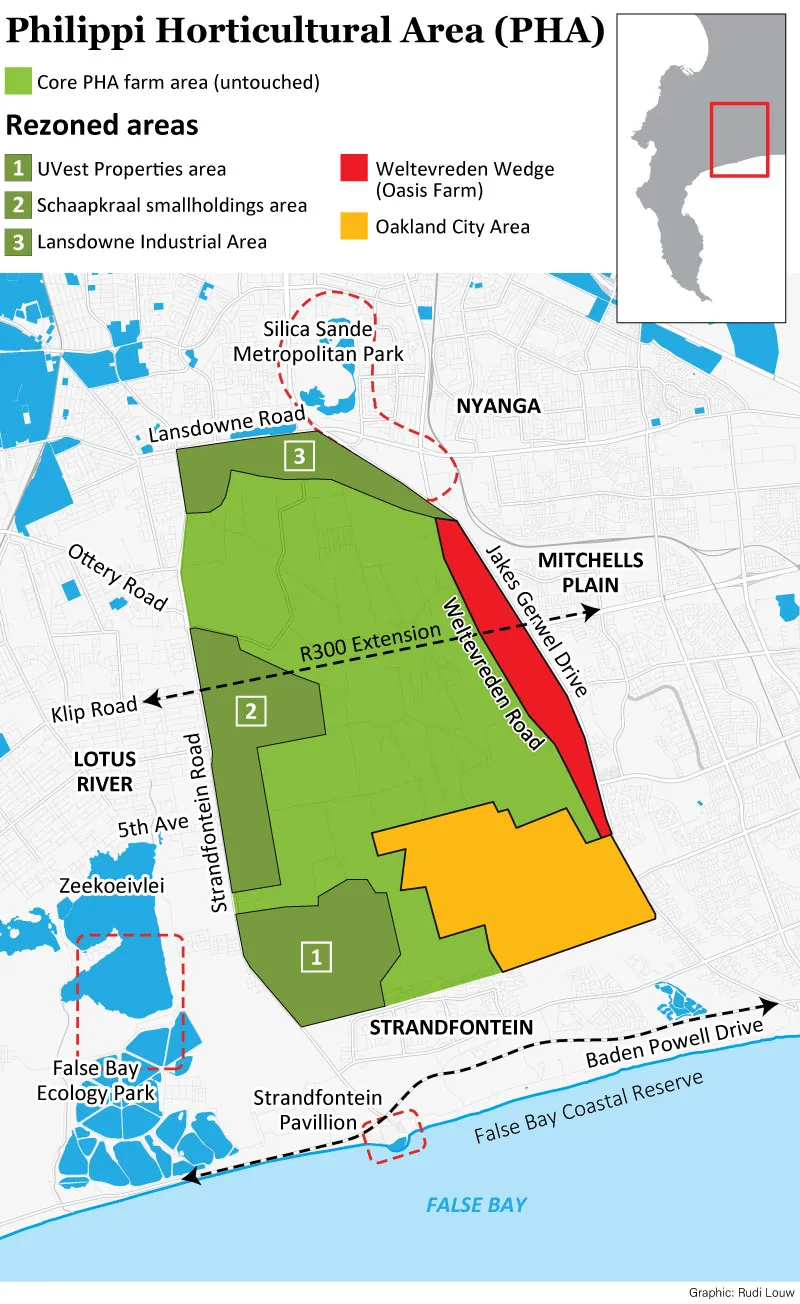

To date, five sizable portions of the PHA have been excised for reasons including urban development and sand mining. These include:

The Schaapkraal smallholdings area, a strip of land along the western boundary of the Philippi Horticultural Area, the Lansdowne Industrial area, the Weltevreden Wedge, a land segment running all the way along the area’s eastern border, and a section near the edge of the eastern boundary which was set aside for commercial development by Uvest properties. Until the court victory last week, the Oakland land of close to 500 hectares was also due for development.

The Philippi Horticultural Area is seen as a crucial barrier to water scarcity in the Western Cape, and is the breadbasket of Cape Town, producing roughly 200,000 tonnes of vegetables a year which supply supermarkets and the informal sector. The PHA campaign says the area also provides 6,000 direct and 30,000 indirect jobs.

Daily Maverick visited a small community of subsistence farmers living on Oasis Farm on the Weltevreden Wedge. The farm is privately owned and made up of smallholdings and informal settlements.

The mostly coloured Rastafarian community is poor and self-sustaining with a strong attachment to nature and are big on sustainable living. Many escaped what they call “the ghetto” to live a peaceful life in the Philippi Horticultural Area where they engage in vegetable and livestock farming to earn a living.

The majority see farming as more than just a food source but a way of life.

They first settled there about 30 years ago when the owner of the land allowed tenants to move in.

As time has gone by, the small farm (which got its name from a now dried-up wetland on the property) has been fraught with problems.

An informal settlement has mushroomed on the property, creating tensions with the subsistence farming community who have also battled with illegal dumping and a devastating flood in 2013.

But this is the least of their troubles.

In 2009, the Weltevreden Wedge was earmarked by the City of Cape Town for urban development.

The plan was to build low-cost housing on a portion of the land. It’s unclear whether this will directly affect the dwellers on Oasis farm, but they are under the impression that their homes are under threat.

For 10 years, the looming fear of bulldozers and eviction has been hanging over the community’s head. Some have downscaled or halted their farming efforts for fear that on any given day it would all be taken away.

The Western Cape Department of Human Settlements seems to have plans to build low-cost housing on 52 hectares of the Weltevreden wedge. Written in their 2019/20 Annual Performance Plan, the department says it purchased the land for R90-million to build social housing.

The community’s concerns extend beyond their portion of land. They fear that the threat to the aquifer will have a ripple effect, spelling the end of farming on the PHA, and in turn, the end of their way of life.

Despite this, the campaign said it would not be contesting the rezoning of the wedge:

“We were never going to oppose it and you can’t because it was by a (city) council vote,” said Susanna Coleman, a representative for the campaign.

Nonetheless, the community holds hope that if the PHA succeeds overall, they will get to hold on to the land, which some say “changed their lives”. The bigger dream for dwellers on Oasis is to upscale and become medium or commercial farmers. They hope each little victory will afford them and their children that future.

TIMOTHY MAASDORP

Timothy Maasdorp has joined the fight against urban development in the Philippi Horticultural Area. The father of two has lived on Oasis farm for more than two decades and believes construction on the PHA will disrupt the area’s delicate ecosystem. 22 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

‘Life here is like a spiderweb.’

says Timothy ‘Tim’ Maasdorp. “If you poke a hole in it, you destroy the whole thing.”

Like many who’ve lived on Oasis Farm for 30-odd years, Maasdorp arrived with nothing.

After hearing that there were cheap plots of land to rent in the area, he jumped at the opportunity and left his home in Elsies River. Years later, he’s built himself a wooden house where he lives with his wife, two young children and a 17-year-old boy whom he’s taken under his wing and employed as a part-time goats’ herd.

17-year-old Clayton Steenkamp moved from Tafelsig to Philippi in 2013. He left a difficult family situation to live with Timothy Maasdorp. Clayton now herds goats, does gardening and general mechanical work for the Maasdorps who have taken him under their wing. 22 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

He believes any form of development in the Philippi Horticultural Area will upset the delicate balance of the ecosystem and rip apart the community of Rastafarians living on the fertile land.

“If you think of the plants, the life, the humans, everything is a string in the spiderweb,” said Maasdorp, who cannot understand why developers are so determined to transform the Philippi Horticultural Area into a “concrete jungle”.

Dressed in military-style khaki, with short brown dreadlocks, Maasdorp, like other Rastafarians, believes in clean living. He’s a vegetarian and grows his own produce.

At one point, he considered himself a small-scale farmer, but costly barriers stood in the way of his livelihood.

“They started dumping rubble here on Oasis Farm,” he explained. When rains came, the runoff from the rubble affected the soil, making it difficult for vegetables to grow. Worse still, the wetland exits were blocked by the rubble which in 2013 caused a devastating flood in the area.

“We lost our animals, some people lost their homes and had to rebuild,” he recounted.

Maasdorp is a firm believer in permaculture, a sustainable and organic approach to farming which avoids the use of pesticides and other man-made materials. He asserts that permaculture will protect the aquifer from pollution.

For Maasdorp, the threats of development could mean losing the place that changed his life.

He left a life of gangsterism behind when he was introduced to farming by an old friend from Elsies River named Deon van Wyk.

“If it wasn’t for him,” he says, “I’d be dead by now.”

DEON VAN WYK

“Farms are important in this country, we need food security,” says Deon van Wyk, who abandoned his dreams of becoming a farmer after a motorcycle accident left him mildly paralysed. Now he runs a small courier business from his garage. 29 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

‘We need food security in this country.’

Deon van Wyk abandoned his dream of becoming a farmer after a motorcycle accident left him mildly paralysed. Now he runs a small courier business from his garage.

“I don’t want people to know me for my disability, I want them to know me for my capability,” he asserts, refusing any help while getting in and out of his chair.

The 49-year-old lives in Elsies River but has strong ties to the Philippi Horticultural Area. He’s seen as a figurehead in his community after starting a horticultural movement in the late 1990s which helped many youngsters, like Tim Maasdorp, escape the pull of gangsterism.

“We turned dumping grounds into peace gardens,” he explains.

His passion for farming grew and soon enough he was growing and selling his own produce in the Philippi Horticultural Area. By the mid-2000s he was supplying vegetables to Epping Market, the biggest and oldest fresh produce market in the Western Cape.

24-year-old Marchellino stands in what used to be a rubbish dump in Elsies River. It was transformed into a ‘peace garden’ after community figurehead, Deon van Wyk, and a few others planted herbs, flowers, and other vegetation 15 years ago. It is now a safe haven for some of the boys in the area to escape the pull of gangsterism. 29 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

“Farms are important in this country, we need food security,” says Deon, who despite efforts to expand his agricultural endeavours faced multiple barriers to becoming a commercial farmer such as lack of access to funding and procuring a bigger piece of land.

He believes that development in the Philippi Horticultural Area is a huge threat to the little arable land South Africa still has.

“And they want to take it away and build a concrete jungle.”

But Deon has continued to teach local youth the value of farming. Around the corner from his home is one of the first peace gardens he planted. Rosemary bushes, grapevines, lemon and palm trees have overtaken what used to be a rubbish dump. Within is a small Wendy House where a few young guys hang out – including Deon’s son.

The garden now attracts small wildlife which Deon says is a welcome distraction from the noise of the township.

ROSLYN STEYN

Roslyn Steyn calls PHA her ‘little piece of heaven’. She loves nature, gardening and animals. Steyn isn’t against development but believes building wooden instead of concrete structures in the PHA will preserve the area’s natural beauty. 22 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

‘Our little piece of Heaven.’

Back at Oasis Farm, it’s another cold morning. Roslyn Steyn has just waved goodbye to her husband and two of her children as they head off to school. Now it’s time for her to open up her small farm stall where she sells chickens, rabbits and vegetables.

She lives a short distance from Tim on a small plot she calls her “piece of heaven”. It’s where she ran to escape the difficulties of the “ghetto” and draw near to nature.

“I’m not saying we don’t want development here,” she explains, “I’m just saying the place doesn’t need to be covered in concrete.”

Roslyn and her husband moved to the Philippi Horticultural Area 19 years ago when the area was still mostly bush. They cleared the ground and built a wooden home which houses the couple and five other family members.

“We got married here, our kids were born here, we lost loved ones here,” says Roslyn, who was once a backyarder in Mitchell’s Plain.

She believes that wooden, instead of brick, houses should be built to preserve the natural integrity of the Philippi Horticultural Area.

“The ground is rich. Anything can grow here. So if you put concrete, all of this will be gone,” says Roslyn, who has a small garden of her own where she grows fresh produce, herbs and other plants.

Many on Oasis Farm cannot afford adequate healthcare, so they use indigenous plant knowledge to create their own remedies.

“We use Buchu for chest pains,” she explains. “We also have (Bulbinella), lavender and rosemary, which we use to treat itches and cuts.”

Bulbinella is an indigenous medicinal plant. The leaves are used for skin ailments such as cuts, burns, sores and eczema. The roots are ingested and used to treat kidney issues, arthritis, diarrhoea, infertility and blood circulation. 2 November 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

They crush the plants and combine them with petroleum jelly.

More so, she believes the low-income community could use a lot more help from the municipality in terms of tarred roads, street lights, proper sanitation and a library.

“Some of the kids have to go to Lentegeur library and they end up robbed because they come home past 6pm.”

For Roslyn, Oasis Farm is a self-sustaining community where people care for one another. One of her dreams is to grow a community garden where everyone can have access to sufficient food. She also has plans to raise funds and help those children who cannot afford an education to go to school.

“We don’t want unnecessary things, only what we need.”

MARINA O’DONIS

Marina O’Donis moved to PHA with her husband Michael in the 90s. The pair now run a small backyard creche which services the community. She fears that development in the PHA will mean losing her plot of land, the creche she’s built and ultimately the children she cares for. 22 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

‘These are all my children’

Marina O’Donis and her husband Michael were among the first “rastas” to settle on Oasis Farm.

“When we first came, there was wildlife, indigenous plants, bird species you don’t see anywhere else,” says Michael, who cleared a small portion of the land and built a small wooden house.

Now they run a creche from their backyard which services the community.

Marina takes us around to see the creche which is also made of wood. The couple built it themselves and have plans to extend the building to accommodate more kids.

With all the children running around, the place “feels like an orphanage”, said Marina, jokingly.

“Many parents of the children are domestic workers,” she explained. “Some work on the farms (nearby).”

She’s clearly in her element while holding a little boy nicknamed “Mini Cooper” in her arms.

‘These are all my children. They belong to me,’ says Marina O’Donis who runs a small backyard creche with her husband Michael. She loves children and although she doesn’t have any biological kids of her own, she’s fostering two teenagers whom she plans to adopt. 22 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

This is the second daycare on Oasis Farm. The other is located just a few metres down the road, but has reached capacity. The O’Donis family opened their doors in September 2019 after a few desperate mothers in the area had asked them to do so.

Near the daycare, they have planted a small vegetable garden, where the children are encouraged to learn about horticulture. A small stage has been built near the entrance to their property. This is where the kids put on concerts and other shows for the community.

“We’re looking for funding,” said Michael, who has approached a few organisations for sponsorship.

Marina doesn’t have any biological kids of her own, but is currently fostering two teenagers, whom she plans to adopt.

She fears that development in the Philippi Horticultural Area will mean losing her plot of land, the creche she’s built and ultimately the children she cares for.

“These are all my children. They belong to me,” she says emphatically.

CHRISTOPHER and COOKIE DU PREEZ

‘I’ve been staying here for nearly 50 years,’ says Cookie du Preez who moved to PHA when she was 13 years old. The Du Preez have been married for 36 years and run a small apostolic church, located a few metres from their front yard. They’re afraid of losing their home due to the pending development. 29 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

‘It’s not always safe here, but this is our home.’

Cookie and her husband Christopher du Preez have been married for 36 years and own a small apostolic church, located a few metres from their front yard.

They’ve been running the local church for four years, and despite numerous break-in attempts, they say it is doing well.

“We know it’s not always safe here, but this is our home.”

Cookie is the third generation to live and work on Lorraine chicken Farm (adjacent to Oasis Farm). Both her parents passed away there.

“I’ve been staying here for nearly 50 years,” says Cookie, who moved to the Philippi Horticultural Area when she was 13 years old to join her grandfather and mother.

Cookie now works as a home-based carer for the farm owner Leon’s 82-year-old mother.

Christopher isn’t sure about the nitty-gritty of the various development plans but is gravely concerned about what effect they will have on the community.

“What about the cattle and the sheep, where will they graze?” he asks. “Where are people going to eat if they can’t grow food?”

His biggest concern is the possible job losses for farmworkers and small-scale farmers in the area.

The couple admit that although they love their home, if the opportunity arises, they will move due to safety concerns.

But in the short term, they fear that any pending development means they will lose their home, without which they have nowhere else to live.

KENNY HERMAN

‘I love my lifestyle, I wouldn’t change it for anything,’ says 60-year-old Kenny Herman who has lived in PHA for more than 20 years. He makes most of income selling fresh produce to the locals, and fears development in PHA will pollute the Cape Flats Aquifer which makes farming possible in the area. 22 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

‘This is where I’ll pass the flesh.’

Kenny Herman explains the Rastafarian idiom for death, “pass the flesh”. He’s a talkative 60-year-old man who struggles with kidney problems. He often walks slowly and breaks into sudden coughing fits.

Despite his struggles, he makes a fuss about making sure we’re comfortably seated in his lounge.

“I built this house myself,” says Kenny, who moved to the Philippi Horticultural Area in 1994.

“It’s mostly made of wood and concrete.”

He’s a proud rasta, who, when asked what Rastafarianism is all about, responds with what sounds like a riddle:

“A Rastafari is an ancient man, living in the present, for the future.”

Kenny is close neighbours with Tim. Both men believe in clean living, in accordance with their faith.

“We try to be organic, no GMOs or anything like that.”

He and his wife Glenda make most of their income selling fresh produce.

“Everything that’s in season we grow: beans, spinach, butternut, brinjals, string beans.”

He and Glenda recycle most of what they use and try to avoid food waste by turning some of the crops they don’t sell into jams and preserves.

“I love my lifestyle, I wouldn’t change it for anything,” says Kenny, reminiscing on his earlier days on the farm:

“In the middle of this bush, we used to swim. The water was clean. You wouldn’t get sick from it.”

‘Kenny Herman in front of his house. 22 October 2019. (Photo: Sally Low)

For years Kenny tried unsuccessfully to become a small-scale farmer. He used to raise pigs and goats but many of them died or were stolen.

“We’d slaughter pigs, cut them into chops and sell them.”

He says many farmers in the area have scaled down their operations due to the increased rate of theft in the Philippi Horticultural Area.

“They have anxiety over whether they can harvest,” he explained.

Added to his woes, Kenny faced a lot of “red tape” when trying to apply for grant funding.

“Because I don’t have a 20- or 30-year lease,” he claimed.

“We know we can’t compete with those big farmers, but there’s a place for us.”

Kenny, who moved to the Philippi Horticultural Area from a council flat in Steenberg, said he doesn’t want to go back to a “ghetto” lifestyle.

“There was no yard. If you stood on the corner the cops would harass you.”

Trapped indoors, he eventually became an alcoholic.

“I didn’t know what to do with myself.”

He is completely against development and believes RDP housing, or any other “cramped” living conditions, aren’t healthy for society. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider