Jim Bailey, 100 years later

Remembering the extraordinary life of SA’s original media maverick

There are some people who do not fit the frame of ordinary mortals. In their wake, extraordinary things generally happen, but quite often also chaos and consternation. They are by nature disrupters. James Richard Abe Bailey, born 100 years ago (October 23, 1919), was such a man.

‘When I looked at the whole enterprise quietly and coldly it appeared impossible. This held a quaint charm.’ – Jim Bailey

But inside that singular languid, easy-going frame were in fact many Jims.

One of those, which he always carried, was an unhappy child in the midst of material luxury. Though he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, his parents hardly warranted the epithet.

His father, Sir Abe, was a fabulously wealthy gold and coal magnate who spent most of his time in South Africa, far from the London house and sprawling estate where Jim grew up. Abe, somebody commented, was “possibly more interested in his racehorses than his own bloodstock”.

Jim’s mother, Lady Mary, was a daughter of Lord Rossmore, an aristocrat fallen on hard times. She was a daredevil pilot who, in 1928, flew from London to Cape Town and back (the first woman to do so) in a flimsy, open-cockpit de Havilland Moth – one suspects to get away from family responsibilities. His parents’ arguments, Jim remembered, were nuclear.

Jim’s only bright memories appear to have been a warm relationship with the gamekeeper on the Bailey country estate, Alan Howe, who taught him to hunt and fish. The memory of his London days was captured in a comment he made on leaving England. It was, he said, to “escape stuffiness and the odour of stale mink”.

Young Jim Bailey, circa 1932 (supplied)

Another Jim was a fighter pilot and war hero. After studying at Oxford – and despite hating war – he joined the Royal Air Force “because it seemed the right thing to do at the time”. At the age of 19 he was flying Hurricanes, then Beaufighters in the Battle of Britain. He shot down six German planes and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (he would later be given a Commander of the Order of the British Empire medal for his work on Drum).

When the war ended, having witnessed the death of many of his friends, Jim’s thoughts were saturated by post-war gloom and possibly survivor’s guilt. “I want a Chair of Evil,” he wrote, “a college of ill-doers, bursaries for subtle destruction.” In his book about the war, The Sky Suspended, he afterwards noted: “I had never been bold enough to dare to believe I should live.”

War, he felt, was in the end terribly wrong. “It is not so much that we have to die that permeates our existence with mystery, it is that we can kill, that it is within our power to destroy other people.”

A third, and most abiding Jim, was a maverick media mogul born, one suspects, partly out of his disgust of apartheid and an instinct to disrupt it. His father died in 1940 and, shortly after the war, Jim came to South Africa to sort out the family estate. He realised he could make Africa his home and planned to settle on his father’s racehorse stud farm near Colesberg.

Much of Abe’s estate was sold to the Oppenheimer empire, but Jim invested what remained and was still extremely wealthy, making a small fortune out of a larger one.

With his inheritance, he could have become a playboy and a lout. Instead, he became something altogether different: a warrior for the rights of Africa’s poor and a fierce critic of the South African government at a time when it was dangerous to do that. He spent his father’s and his own fortunes in ways that would have made the old man apoplectic.

Another Jim was the way he presented himself in person which was outrageously anti-establishment. Describing the first meeting of his new boss on West African Drum, Nigerian journalist Nelson Ottah remembered: “In sauntered a lean-looking white man in short pants that looked slept-in, unpressed short-sleeved shirt rolled to the shoulders and who was incongruously munching an apple. The word ‘tramp’ came to mind.”

Without his devoted second wife, Barbara Epstein, the chaos of his personal life could have been considerable. The historian Thomas Pakenham once noted that without her and the children, Jim might have lived in a barrel-like the Greek philosopher Diogenes. Barbara never managed, however, to instil in him any dress sense or to remember to wash the soap out of his hair. “The only suit he ever owned,” she remembered, “was a wetsuit for spearfishing.”

He first met her when she was 11 and she fell instantly in love with the dashing 32-year-old fighter pilot. “I didn’t want to marry him,” she wrote, “as much as I wanted to be him. When he walked into a room my heart leapt. When his car drove in to our drive my heart leapt.”

Loving Jim wasn’t going to be easy. On first meeting, he “threw a dachshund at me”. Then he broke her young heart by marrying “a pretty blonde schizophrenic” named Jill Parker, who later ran off to Canada. Barbara considered suicide, but instead married the musician Jeremy Taylor. That didn’t last too long. Jeremy ran off with a member of the cast of Wait a Minim!, the show he was involved with.

Barbara had never stopped loving Jim. When, in 1964, she and Jim eventually announced they would marry, her mother told her: “Darling, Jim’s a wonderful man, but he’ll make a most dreadful husband.” Barbara brought along a curtain ring “because Jim would never remember a wedding ring”. The marriage lasted 40 years, though for the first 25 he was often away for six months or more “somewhere in Africa”.

“I knew when Jim was going on a trip,” their soon Beezy remembered, “because Barbara would be crying.”

Jim the family man was mostly emotionally absent, which led Barbara to ponder whether he was in fact on the Asperger’s spectrum.

“We kids lived in a house in Johannesburg and Barbara and Jim lived on the farm at Lanseria,” said Beezy. “A driver would take us out on a Friday to spend the weekend. If we made a noise anywhere near Jim, Barbara would go ‘Shhh, Jim’s reading the newspaper.’ He was never really present to us. He spent much of his time in his library. And every few weeks he was on a plane going somewhere. But whenever we really needed him for something he was there for us.”

Prospero, Beezy’s brother, agreed: “Jim was ambitious and infuriating to work with, but always original and far ahead of his time. But in his final years after Drum he was more supportive and loving.”

Jim’s daughter, Jessica, described Jim as “a giant of a human being, not always easy to live with but one most the most admirable people I have ever known. It is more in retrospect that I’m able to distill what he left with me: the ability to be myself without a need to follow the herd.

“Jim and I had a silent understanding, he being unable to talk about everyday things and me being too young to appreciate the value of his extensive knowledge. What we did share was the ability to giggle uncontrollably in serious situations.”

Another Jim was an expert on the Bronze Age about which he was hugely knowledgeable, owning a library full of books on the subject and able to read both Ancient Greek and Latin. His book The God-Kings and the Titans was a controversial work on pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact, which claimed that thousands of years before Christopher Columbus sailed west, sophisticated Bronze Age voyagers from the Old World had landed on both the Atlantic and Pacific shores of America.

Jim’s involvement with the media world and, particularly, Drum magazine, is what he’s most remembered for. It was to be a trajectory through the African firmament that was glittering, gutsy, controversial but definitely not profitable. According to Beezy, “over 40 years Jim spent many millions on Drum.”

“I came into publishing by chance,” Jim wrote, “and stayed with it out of conviction. I enjoyed a thumping income, but believing that one can only eat three meals a day, I diverted it to building a publishing machine that stretched from Cape Town to the boundaries of the Sudan on the East Coast and to Liberia on the West Coast of Africa.”

A professional cricketer, Robert Crisp, had started African Drum as a liberal enterprise “presenting blacks as noble savages”. Jim bought shares but discovered it was failing to get traction. So he paid out Crisp and relaunched it as Drum with a completely different philosophy.

“It was clear from the start that I was producing a vehicle, not a voice, that it should be a vehicle for sound black opinion, not for my opinion, nor for white opinion generally. The white hand… had to be kept out altogether.”

Its new editorial policy would concentrate on crime, sex, sport and pin-up photographs. It also quickly became the voice of black unrest, of segregation misery and political aspiration as well as a vehicle for township culture.

Jim appointed his Oxford pal Anthony Sampson as editor. Without any experience, he was perfect for the job: “I left the black journalists to write in a style which offended all the laws of Fleet Street,” he confessed, “but which had a vigour and freshness that came from the heart of the townships.” Drum‘s writers were free to riff in an inventive, hybrid, syncopated style that became known as Drum Style.

Johannesburg, and particularly Sophiatown, of the 1950s became the fulcrum of Drum’s Africa-wide balancing act. Alongside the city’s gold mines and bleak migrant labour compounds was a sophisticated city of black shebeens, dance halls and snappy dressers where life was lived fast and on the streets. It was this world that provided much of Drum’s creative talent.

It also took black African women out of the kitchen and into mainstream urban culture, with covers featuring sexy black pin-ups who became superstars.

The way the magazine dealt with the oppressive atmosphere of apartheid was essentially an extension of Jim’s personality. It orchestrated laughter and outrage in equal measure. According to Pakenham, “it dealt with the dismal architects of apartheid as they deserved – with wit and mockery. It shouted to the heavens that apartheid was worse than crime – it was simply ridiculous.”

The magazine would expose the evils of the racist system without actually condemning the official policy. The irony appeared to confuse the censors and it was banned less often than even Jim expected.

Within a year, Drum was circulating in East and West Africa – the continent’s first international black magazine. On a whim, Jim employed Henry Nxumalo. He was maddening and would disappear for days on end. But he was indispensable and his courage and approach were novel and outrageous.

He became known simply as Mr Drum and led exposures in the Bethal potato farms by becoming a labourer where flogging was rife. He deliberately went to jail, enabling a photographer to acquire (from a nearby rooftop) proof of indignities meted out to inmates.

Staff members of the early years read like a roll call of African creative greats: Nxumalo, Todd Matshikiza, Can Themba, Es’kia Mphahlele, Nat Nakasa, Lewis Nkosi, Casey Motsisi. Photographers later to become famous first handled a camera in Drum’s darkroom. They included Bob Gosani, Peter Magubane, Jurgen Schadeberg and Alf Kumalo.

Some of Drum’s writing stars: Can Themba, Henry Nxumalo and Nat Nakasa (Photos supplied)

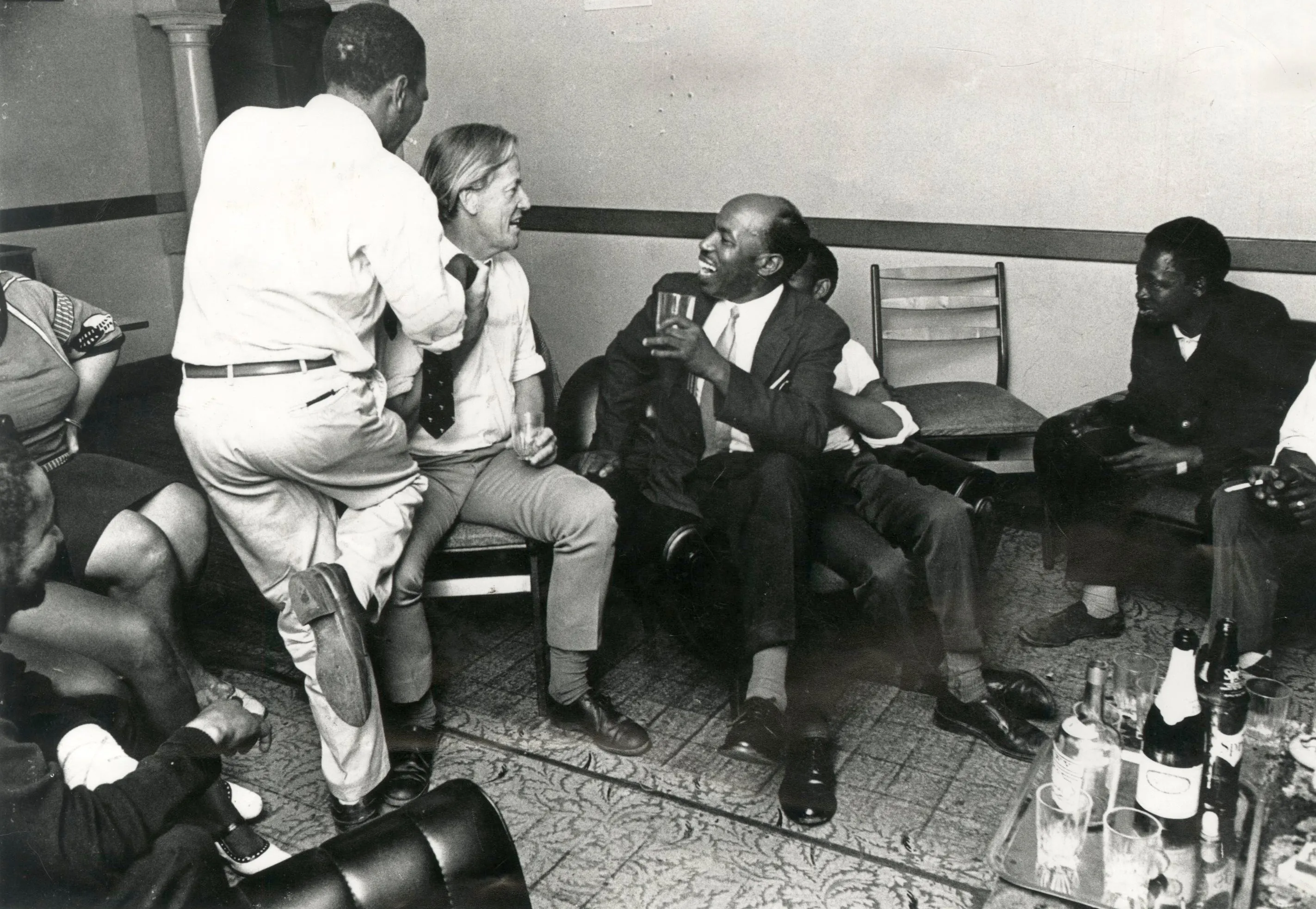

Holding all this together had Jim flying between Johannesburg, Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya, appointing staff, organising distribution and putting out political fires. Stories circulated about Jim’s outrageous ideas as the booze flowed in exotic places or low dives, of disorganised parties with incompatible people, of beautiful young black bodies squirming on accommodating laps. Jim didn’t drink much at these sessions, but liked to supply the hooch and watch people to see what would happen.

He had, as someone observed, “a long sense of history which gave him a detachment” as well as a laugh that went rolling down the street. That laugh, remembered Ghanaian Drum editor Cameron Duodu, “featured whether he was sipping a beer in a dingy Lagos nightclub, a Johannesburg shebeen or a svelte hotel dining-room”.

He had a unique gift of turning people’s lives upside down. “He was a great disrupter,” Anthony Sampson remembered. “He was always shocked by watching people get duller. He asked us to do things we didn’t think we could and then left us to do them.”

Kerry Swift recalled that working on Drum “you had to learn to see all over again and to understand in a deeper way. Jim wasn’t a commercial publisher at all. Essentially he was a secular missionary. His publications became mass popular educators and trusted advisers in societies where the vast majority of people had no access to an education.”

In the end, however, it all slowly unravelled. The 1950s – the decade of black literary innovation – crashed into the decade of oppression which followed the Sharpeville massacre and the banning of the ANC. Many of the Drum writers fled or succumbed to alcoholism. Nat Nakasa committed suicide in New York. Nxumalo was stabbed to death in a back alley.

1970s Drum staff, Jim Bailey with Alf Kumalo at Kliptown Shebeen

©BAHA Photographer Alf Kumalo

Jim’s publications ran into problems, not through the lack of innovation, readership or advertising, but from forces beyond his control which were building up against him.

He had started a Sunday newspaper, Golden City Post, alongside Drum. It was hugely successful until the Argus Company said it would close down the distribution network (which Argus owned) unless he sold the paper to them. He refused and it bankrupted the paper. Jim had to sell his large Karoo farm to pay off the debts which followed.

He opened another paper, Golden City Press, but its success became its demise – with the same story. The SAAN Group, which had shares in the paper, gave him the choice of selling his shares to them or they’d deny him access to their distribution network. He refused and they pulled out.

The paper was declared bankrupt on a Friday. The next week Jim set up a company and continued publishing as City Press.

Eventually, Africa got in the way of his continental dream. Its distances were too huge, its roads and railways too often temporary, it’s politics unpredictable. Drum, which once boasted a circulation of 400,000, was losing money.

In 1984, feeling his age, he sold Drum, City Press and True Love to the Afrikaans media giant Naspers. Afterwards, an employee who stayed on said: “We have offices in Sandton and Mercedes-Benzes but we’ve lost our soul.”

Drum had been Jim’s mistress. When she left him he was inconsolable. He became reflective.

“In the miserable days when the great Sunday newspaper Post collapsed around me, when I had to sack 150 good and loyal men, when the sharks rose up from the deep to snatch their mouthful and various parasites crept from the wainscoting of my debts, it was natural to hark back nostalgically to the days of the beginning; to the chair, the table and one wastepaper basket, when we purchased our first typewriter with the sentiment of affluence.”

Without a media presence, Jim now found he had few friends.

“It was so utterly tragic,” said Beezy. “He couldn’t understand that when he sold Drum it all just melted away. Then he realised it was because he was Drum that they were friends. When he wasn’t, they weren’t. He couldn’t believe it. He started drinking heavily and slowly fell apart.”

From left Aggrey Klaaste, Lefty Maruping, Don Matera, Dolly Rather, Jim Bailey, Mike Mzileni ©Bongani Mnguni

Towards the very end, as Alzheimer’s took hold, he was a nine-year-old again on a large estate with few friends other than Barbara, his faithful African gamekeeper. Now he fished for memories and hunted for meanings. If his media friends forgot about him, his unspooling mind forgot them. He died of colon cancer on his farm at Lanseria on February 29, 2000, aged 80 with his family at his side.

Hobo, loner, family man, millionaire tycoon, war hero, author, historian, newsman, hellraiser and sensitive poet, Jim had been them all. DM

For more information:

Bailey’s African History Archives

Drum, the original beat of Sophiatown’s heart

Saskia Bailey (Jim’s granddaughter): Whatever

Don-Jim-Inset 2 of book cover here

Become an Insider

Become an Insider