AMABHUNGANE

ANC gambles on Twitter influencers

The party of liberation appears to have bought into the fake politics of paid Twitter, an amaBhungane investigation has found.

“My job is to influence. Influence other people’s opinions, influence their interests, influence anything … fashion, music, clothes, any sort of thing like that.”

Karabo Motsoane is an influencer, a social media guru who has leveraged his popularity on platforms like Twitter and Instagram to make money by promoting products and events to his followers.

He and his girlfriend Zukhanye Ncapayi – also an influencer/“full-time muse” – have their own YouTube channel where they post adorable videos of their exploits as a couple to their 18,000 followers.

On Twitter, their following is even bigger.

“I get paid per tweet or per post. That rate, I align it with traditional media advertising. I have 35,000 followers on Twitter, and there’s the potential of my tweet being seen by double that amount, by 60,000 people, so I look at how much you would get charged in a magazine or TV for 60,000 people being reached, and then that’s what I charge… it’s very straightforward, I have a rate card…”

I have asked Motsoane if I can interview him about the influencer industry and his role in two campaigns linked to the ANC.

We are sitting on the balcony of the ad agency where he works, overlooking the N12 highway. I am sitting a little too close, making sure my recorder picks up his answers. He does not back away though; he is warm and personable and friendly.

If my theory is right, he is also not telling the whole truth.

Down and dirty in Joburg politics

I first encountered Motsoane online when he was tweeting about an article I wrote on Geoff Makhubo, the chairman of the ANC’s Johannesburg region, receiving millions from Regiments Capital, a consulting firm associated with state capture.

“I’m glad that Geoff Makhubo responded to these outrageous accusations perpetuated by @HermanMashaba. The DA is tiring,” Motsoane (@Tswana_Guy3) tweeted at 2:04pm on 11 December, adding a link to Makhubo’s 6-page response to amaBhungane’s investigation.

“Guys beware of the DA’s tricks,” he tweeted a few minutes later. “Instead of telling us how they’ll make our cities & countries a better place, they just attack the ANC & it’s members, like Geoff Makhubo.”

For the record, I do not track down everyone who has anything negative to say about my investigations. But there was something unusual here: In the space of 10 minutes, Motsoane posted six tweets about Makhubo along the same theme: that the allegations against him were a DA-plot to undermine the ANC ahead of the elections.

“I was going on a Twitter rant…” Motsoane told me a month later, sitting on his office balcony. “[A] lot of people were saying, ‘It’s paid promo Twitter’ … even some of the influencers that I work with, they were asking me, like ‘Why didn’t you hook me up for the campaign?’ And I was like, ‘Nah, nah, it’s not a campaign, I’m just tweeting on my own accord.’”

But Motosane was not alone in rushing to Makhubo’s defence. For 25 minutes, Twitter – which had largely ignored Makhubo’s 6-page “right of reply” all morning – came alive, with 63 tweets from Motsoane, his girlfriend and 13 other accounts, all repeating the same narrative. They then followed up retweeting each other about 200 times.

@[redacted]: It is further concerning when that is supposed to be a respectable media organisation picks and chooses which responses to publish and how to frame these” – with DA being the driving force behind these allegations cause white propaganda protects the white agenda

(Note: Where we were unable to reach Twitter users for their comment, we have redacted their names and handles.)

Then, at 2.25pm, Motsoane and his friends went quiet. But as their tweets and retweets started filtering through Twitter’s timelines, other users called foul.

@SbongileDreamer: “So now ANC/Geoff Makhubo hire people to tweet, wonder how much they got paid to promote statement, if innocent why hire people to tweet your innocent statement…Jeso so they honestly think we will believe their twitter campaign it raises lot of questions rather.”

“[T]hat wasn’t really a campaign per se, it was on a personal scale,” Motsoane said when I told him it looked like someone had hired a group (or “pod”) of influencers to attack Makhubo’s critics.

“[I]t was just me and my mates that were tweeting for Geoff Makhubo … voicing our opinion, saying, ‘There’s so much going on in the City of Joburg and [the DA is] focusing on badmouthing a potential candidate that’s going to run for … mayor during election time to make him seem bad, when you’re not really trying to fix the issues that we are facing in Joburg.” (Makhubo will not, in fact, be eligible to run for Johannesburg mayor until the 2021 municipal elections.)

Focusing on the DA and its mayor Herman Mashaba was a clever sleight of hand.

Although the investigation implicating Makhubo was published by amaBhungane, Mashaba had seized the opportunity for political theatre and laid corruption charges against Makhubo at the Johannesburg Central police station. Painting the allegations as a partisan war between political rivals – and the media as stooges – was both ingenious and cynical. But was it co-ordinated and deliberate?

“It wasn’t coordinated but the conversation was happening at that point in time with everyone… Yeah, it was deliberate, on our own accord, it was deliberate. Everyone was tweeting, and we knew what we were tweeting about, but I think it’s all politically-inclined people who always talk politics…” Motsoane told me.

But when I looked at the profiles of 14 other people who had passionately rushed to Makhubo’s defence, I could see little evidence of this. Instead they looked like influencers and for the most part, their timelines were not filled with politics, but with posts about upcoming events, win-a-car competitions and alcohol brands.

And when I pulled the tweets together into a spreadsheet, a clearer picture of the Twitter storm emerged: With few exceptions, each person had posted four tweets between 2pm and 2.25pm, followed by hundreds of retweets in total, some issued at rapid-fire rates of 15 per minute.

Although Motsoane wavered between describing the tweets as “deliberate” and insisting they were not “coordinated”, what he maintained throughout was that none of the Twitter users was paid, and that neither Makhubo nor the ANC were pulling their strings.

“I remember when I was tweeting about the Geoff incident … even some of my friends on WhatsApp [said] ‘Dude are you working with the ANC now? What’s going on?’” he told me.

Although Motsoane described himself as “pro-ANC”, he said that he would never do paid influencing around “religion and politics”.

His claim, I thought, would be easier to believe if an almost identical series of tweets had not appeared four days earlier.

Makhubo initially planned to launch his fightback campaign on Friday 7 December, the day after the amaBhungane article was published. It got off to a bad start though, and after a bruising interview with Stephen Grootes on SAfm, Makhubo’s communications team allegedly told him to pull the plug.

Despite this, two minor Twitter storms erupted, triggered by Mashaba tweeting a link to amaBhungane’s 3,000-word exposé.

“If only you put the same effort in decreasing the crime in the city as you did reporting on baseless accusations. Is that all you guys do over there by DA ?” @orasuniverse tweeted in response to Mashaba at 10.04am on 7 December.

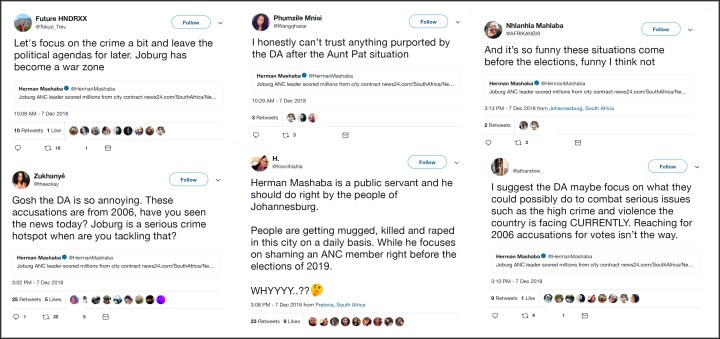

Soon the same group of Twitter users from the later spike of 11 December piled in, repeating the narrative in 58 tweets during two roughly 30-minute bursts, at 10.04am and 3.01pm.

@theezkay: “Gosh the DA is so annoying. These accusations are from 2006, have you seen the news today? Joburg is a serious crime hotspot when are you tackling that?”

While some of the tweets broke out and gained traction with other Twitter users, the majority ricocheted around the same group, amplified by each other’s 274 retweets.

Then, at 4pm, Motsoane and his friends went back to tweeting about parties for the weekend. No one mentioned Makhubo or Mashaba again until 2pm on 11 December.

I reached out to all 15 people involved in what appeared to be a coordinated campaign to protect Makhubo – some of whom have openly identified themselves as influencers, others do not. Only one responded:

“I have not done any paid promotions with any political [party],” @Wangqhazar told me before blocking me on Twitter.

Detailed questions were sent to Makhubo via Johannesburg ANC spokesperson Jolidee Matongo. These also went unanswered.

Buying authenticity … or the appearance of it

Spotting the difference between a genuine post and a paid one is not easy. When the Gupta family and UK public relations firm Bell Pottinger let loose an army of “Twitter bots”, spotting fake accounts became a national pastime.

But with influencers, the people are real; it is just their taste in music, product, or cause that might be influenced by whoever is paying them.

“Bigger corporate brands prefer to script tweets [or] scenes whereas brands without as much red tape prefer if the influencer creates the content themselves for more authenticity,” Tebogo Sethokga, a digital specialist from Whacked Management, told me – one of the few experts willing to speak on-the-record.

And because clients are buying authenticity – or the appearance of it – many people are wary of openly identifying as influencers.

“I don’t put ‘influencer’ on any of my bios … because … people will be like, ‘Ah, everything you do is paid for, I’m not going to take you seriously.’ Which affects the result of your work,” Motsoane told me.

For some influencers, this means cherry-picking brands that will not result in them being called out as “Paid Twitter”.

“I always work with brands that I can align in my lifestyle,” @Tokyo_Trev, one of the pro-Makhubo influencers, states on his webfluential.com profile, a platform where influencers advertise their services. “[F]or example, I would never work with a cognac brand because I have mentioned so many times on social media that I cannot stand the taste of cognac… This makes it easy to promote the brands I work with organically.” (@Tokyo_Trev did not respond to emails.)

Most of the influencers I identified had fewer than 10,000 followers, but industry experts told me that brands were increasingly moving away from macro-influencers – celebrities like Kylie Jenner with 26 million followers – and instead investing in micro- or nano-influencers who are considered trusted voices in a specific topic, whether fashion or politics.

Which, of course, makes it even harder to tell when money is manipulating our public discourse.

The Advertising Regulatory Board would like to make it clearer. If its draft regulations are passed, influencers will be required to include “#Ad” or “#Sponsored” in any paid posts.

But the proposed regulations will only apply to commercial campaigns, not political ones. So, for now, spotting political influencers requires luck… or in the case of the 2018 Wits SRC elections, a Whatsapp screengrab.

The university upon the hill

“There is something special about Wits,” vice chancellor Adam Habib told me.

“All the leaders went here over the decades: Mandela walked these corridors, and Sobukwe taught in them. Helen Zille is an alumnus as is Gwede Mantashe and the ANC notables. The entire top brass of the EFF come from here but as do most of the leaders from business, media, civil society and other sectors.”

This status and its geography make Wits a “city upon the hill” but also a symbolic prize for political parties hoping to demonstrate their credibility with young voters, who remain a massively untapped segment of the voting population.

“This has created a toxic environment where proxy political wars are played out between parties as well as intra-party factions… Political parties are now the curse of South African universities. They ensure that student politics is governed by party paranoia and political spectacle,” Habib complained.

At Wits, the student representative council (SRC) has traditionally been dominated by the Progressive Youth Alliance (PYA) – made up of the ANC Youth League, Sasco and the Young Communists League.

But in 2017, the PYA suffered a crushing blow when the EFF Student Command (EFFSC) took 12 out of 15 seats on the SRC.

2018 would be very different.

At roughly 1pm on 15 October 2018, two rallies kicked off on opposite sides of the library lawns at Wits. On the north side was the EFF’s Mbuyiseni Ndlozi, and at the PYA rally on the steps of the Great Hall was #FeesMustFall activist Mcebo Dlamini.

Photographs tweeted of the two events show the unmistakable red and yellow of their rivals in the background.

It is alleged that halfway through these two heated rallies a message from Motsoane started circulating on a WhatsApp group called “Wits campaign”.

“Afternoon guys. So as some of you might know, SRC elections are underway. And PYA are asking for us to. Promote gor [sic] the for 3 days. They’re paying R100 a day,” the screengrab of the message read.

“I know with politics some people might have a conflict of interest. So please let me know if you’re keen. If you not, I understand and you may exit the group.”

It was the day before the 2018 SRC elections at Wits, and unless the WhatsApp screengrab was a sophisticated forgery, Motsoane was looking for paid influencers to promote the PYA.

Aside from working as an influencer, Motsoane also acts as an agent, recruiting other influencers and coordinating campaigns.

“I have a group of influencers – well, not really influencers, but a group of people who have a large following – I categorise them into pillars: one for entertainment, one would be for lifestyle, one would be for music, etc, and then based on what the client wants and what messaging they’d like to get across, those are the influencers I pick.”

Industry experts peg fees that influencers can normally earn at between R500 and R10,000 per Twitter or Instagram post, and up to R200,000 per campaign. But those fees vary when you hire a whole pod of influencers, Motsoane explained.

“[W]hen it comes for me sourcing other influencers and attacking a campaign, it depends on how long the campaign is, but … if it’s a week campaign we charge roughly R10,000 a week,” he told me. “[I]t also depends how many influencers [the client] want[s]… [and] if they want to trend or not. So, if they say, ‘I want 10 influencers and I want to trend’, then there’d be a certain fee for that… Or if they say, ‘I just want to run a campaign and this is my budget, I have a R15,000 budget’, then I adjust and see what I can do.”

So is this what happened during the Wits SRC elections?

Just before midnight on the 15th, the day before voting was due to commence, the PYA issued a statement denying that the screengrab from the “Wits campaign” group was real.

“We would like to clarify that the below screenshot and alleged campaign/WhatsApp group has not been commissioned, endorsed or agreed to by the PYA. This is clearly an attempt by the opposition to derail students and the organization. We have contacted the so-called creators of the group and they have reiterated that it is, in fact, untrue,” the official Wits PYA account tweeted.

But the following day, when the SRC elections began, posts using #VotePYA started appearing on Twitter.

@theezkay: “Voting from home. My vote is going to PYA #VotePYA”

While many of the #VotePYA tweets came from the PYA, its members and the ANC’s Johannesburg region, more than half came from a group of eight apparent influencers – seven of whom would reappear two months later on my timeline, tweeting in Makhubo’s defence.

Unlike the Makhubo campaign, the #VotePYA tweets were innocuous and mostly featured the PYA’s manifesto, its previous achievements and instructions on how to vote for the PYA’s candidates.

While some of the apparent influencers appear to be students at Wits, at least three came from other universities. Motsoane’s girlfriend, Ncapayi, who was “voting from home” (@theezkay), graduated from Wits in 2017, according to her LinkedIn profile, and was therefore unlikely to be eligible to vote.

Two days later, PYA declared victory, taking 12 out of the 13 seats in the new SRC. This was followed by another round of congratulatory tweets from the same group.

@OzzaT_: “To everybody that voted for their favorite candidate u made it possible for @WitsPYA to win majority

@sir_ice1: “Mfanaka roja neg ka this promo?” (My boy when are we going to eat with this promo?)

@AshBoogiie: “Le no Trevor zidla zodwa ngama promo ntwana. Az’faki muntu” (Trevor and this guy enjoy these promos alone, they don’t hook anybody up)

@OzzaT_: “I don’t own promos, I get called up…Level yourself up nawe bazok’biza….” (I don’t own promos, I get called up… Level yourself up they will call you also…)

If this was a campaign, it was a transactional one. None of the eight apparent influencers follows the Wits PYA on Twitter, and the PYA does not follow them back.

When I interviewed Motsoane I had not seen the screengrab about the Wits PYA campaign, so when I found it a week later, I sent a copy to him on WhatsApp, being sure to use the number listed for him in the screengrab.

“There’s nothing more to talk about in regards to that screenshot…” he WhatsApped back. “I wasn’t involved in the creation of any Wits PYA campaign. Nor do I know of one in existence. Any stories or texts suggesting that I was, are false. Influencers I work with on the regular weren’t involved… Especially not from my lead of instruction.”

As with the Makhubo campaign, what bothered me was that Motsoane was not saying “this was an influencer campaign, we did it pro-bono because of our love for the ANC”. Instead, in the face of all the evidence, his line appeared to be: there was no campaign.

Looking at the statistics, I doubt the eight apparent influencers moved the needle much during the Wits SRC elections: there were just 30 tweets during the election and another 40 afterwards to celebrate the PYA’s victory.

On the other hand, even a university like Wits fails to attract a high voter turnout – 2018 was the first time that turnout reached the required 25% mark in six years with more than 10,000 votes. To put that into perspective, a single influencer like Ncapayi has almost double that many followers on Twitter.

But other plausible reasons exist for the PYA’s victory.

Nkateko Mabasa covered numerous SRC elections for Daily Maverick and told me that the feedback from students was that the EFFSC lost at Wits partly because it failed to maintain its revolutionary character once in office.

“From what I heard from students, the Wits EFFSC could not win back the SRC primarily because of two main reasons … [firstly,] they were seen not to be present on the ground with students but were alleged to be always in meetings with management… [And secondly,] the Progressive Youth Alliance came back with renewed optimism with Cyril Ramaphosa as president of the ANC,” Mabasa explained.

But I still wanted to ask SRC president Sisanda Mbolekwa whether she stood by the PYA’s statement that it had not “commissioned, endorsed or agreed to” a pro-PYA influencer campaign during the SRC elections. And if the PYA had not been behind the campaign, then who had?

She initially agreed to meet, then backed out saying she was under a lot of strain with the start of Wits’ orientation week. Since then, Mbolekwa has been on the front lines of the protests that have engulfed Wits.

Would the ANC really pay for loyalty?

For several weeks I have been interviewing ad agencies, booking agents and industry experts about how influencers and their Instagram accounts are changing both the advertising industry and our political landscape.

While most were enthusiastic about the tie-ups between influencers and commercial brands, they shifted uncomfortably when the topic turned to politics.

“It’s more about losing endorsements and other deals than [it being] taboo. Some influencers are afraid if they associate with politics they will be seen as a liability by certain brands [or] companies and lose out on work,” Whacked Management’s Sethokga told me.

Rapper AKA recently pushed back at claims that he was acting as a paid influencer after he tweeted that he planned to vote for the ANC in the May 2019 elections.

@NoxoloWaiza: “Clearly ANC has chosen their influencers for the elections”

@AKAworldwide: “I am not an influencer nor am I contracted or paid in any shape or form by the ANC. I have a platform as a leader in my private capacity as a citizen of the country that I love. I will speak as I see fit with my own beliefs and nobody can silence me or put a price on my voice.”

But one does not have to go far to find evidence that the ANC is has decided to gamble on influencers.

At a gala dinner, held the night before the ANC’s 107th birthday celebration at Moses Mabhida stadium, comedian Nina Hastie tweeted:

@THATninahastie: “What an orator @CyrilRamaphosa speaking – leading up to the #ANC107 #PeoplesManifesto talking about critically examining the past in order to learn from hindsight. “Go back and fetch it” and learn from the blunders, learn from the triumphs and herald the future @MYANC”

Look closely at the photographs that she and performer Lasizwe Dambuza tweeted from the night and you will see “Social Influencers” on the tags around their necks. Both Hastie and Dambuza ignored my emails.

Two years ago, when amaBhungane published a series of articles about the ANC’s endorsement of a secretive election War Room, Twitter users lambasted the party for buying into underhanded political methods, which included using 200 social media influencers to target the DA as anti-black and anti-poor and the EFF for its antics in Parliament.

Two years on, had the influencer industry really come of age?

I wanted to put this question to ANC elections head Fikile Mbalula. My interview request got a quick response from spokesperson Dakota Legoete: “He wants to know the questions of the interview?”

I sent him an outline. Then I sent him four pages of questions with a detailed explanation of all the evidence. More than a month later, I am still waiting for a reply.

A detailed summary of the evidence and questions were sent also to ANC spokesperson Zizi Kodwa. No response was forthcoming from him either.

The race to the bottom

Bell Pottinger, Cambridge Analytica and Russia’s Internet Research Agency have given us a glimpse of what happens when political dirty tricks campaigns find a natural habitat on social media. (Read the report: The Tactics & Tropes of the Internet Research Agency.)

A recent New York Times investigation described it as a “race to the bottom” as political candidates resort to social media manipulation out of fear that their rivals will beat them to it.

I asked a number of the industry experts I interviewed on and off the record if to their knowledge opposition parties also used influencers in their campaigns. The most common answer I got was “no comment”. DM

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism, an independent non-profit, produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB Supporter to help us do more. Sign up for our newsletter and WhatsApp alerts to get more.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider