Dakar ’87

Breaking the Fetters down Memory Lane

One year after the death of political journalist Hennie Serfontein, his journalist and film-maker daughter, Anli, organised three screenings of a film he made of the 1987 meeting between a group of prominent Afrikaners and the ANC in Dakar. So much has changed since then, but still, the aftermath of the apartheid scars run deep.

It’s striking how much absent the grey was in 1987. From the charming man with dense beard, filmed light-heartedly introducing himself to the group of ANC leaders and Afrikaner delegates in the Dakar Novotel as “Thabo Mbeki, I’m an Afrikaner,” to Mac Maharaj, saying “the rejection of apartheid is a significant step in the life of any white person” while he nonchalantly tugged on a cigarette in the meeting (it was the 80s, remember), to journalist Max du Preez (his hair and beard still red-tinged), saying the visit to the slave house on Gorée Island “shook us” because it also symbolised apartheid.

Even my father, Lourens du Plessis, a law professor, was young, at 38 the same age as Elmien, my law professor little sister now. To my 13-year-old self, however, he was very, very grown-up. “For the first time Africa opened its heart to me as a man from Africa, and as someone opposed to apartheid,” my father said in the film.

Oliver Tambo

The Dakar trip and the delegation’s subsequent travels to Burkina Faso (where they met Thomas Sankara, no less, but this wasn’t in the film) and Ghana, were recorded in a documentary called Breaking the Fetters, directed by political journalist Hennie Serfontein and produced by his daughter Anli Serfontein.

At a screening at the Holocaust Centre in Johannesburg on Monday night (the first of three, with Durban and Stellenbosch following), Serfontein said when the film was made in 1987, the ANC was a banned organisation under the State of Emergency regulations.

“There were media laws that made it more or less impossible to work as a journalist,” Serfontein explained. “This is a film that was made in great secrecy.” The editing, over a 16-hour-a-day three-to-four-week period, was done in an Amsterdam hotel.

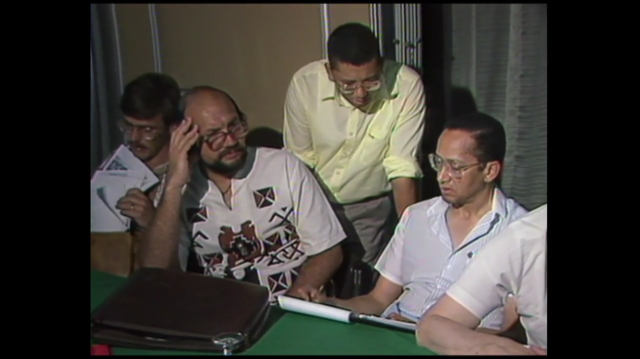

Gerhard Erasmus, André Odendaal, Jaap Durand, Hennie Serfontein, foreground.

ANC leaders flew into Dakar from the countries they were in exile, and, together with their Senegalese hosts, greeted the white delegation warmly, in Afrikaans, upon touchdown. Those flying in from South Africa had to lie about their mission, even to loved ones, lest their passports were confiscated before they even got on the plane.

The anti-apartheid struggle, for much, was black and white. By the late 1980s apartheid was clearly unsustainable, morally as well as economically and politically. Internationally too, and in Africa, South Africa was largely isolated.

Still, there was political deadlock in the country, but Serfontein showed the Dakar meeting to have been the first of at least 167 similar meetings between white and black.

“We view it as a matter of vital importance that white people should join our struggle and become part and parcel of the democratic forces of our country,” Mbeki told delegates. “Those that travelled to Dakar have taken that decision already.”

At home, however, some white people kicked hard against change, such as extremist Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging leader Eugene Terre’Blanche, who vowed to blast those “who want our country… low with the gravel”. Him and a bunch of even more extremist Wit Wolwe formed a threatening throng at the Jan Smuts Airport arrivals terminal when the Dakar delegation returned, which meant my dad and others entered quietly through a back door for fear of violent confrontation. That day my teenage self knew I’d never be on the same side as these people in a race war.

Then defence minister Magnus Malan (there was a slight gasp from the audience when he flashed onto the screen, much because of what we know about him now had a ideologically more sophisticated argument: “We sit with a communist onslaught led by the South African Communist Party and the ANC, which is dictatorially aimed at putting up a small group of small elite to govern this country.”

South Africans from all sides who had never met mingled at Dakar.

On the other side was opposition Progressive Federal Party leader Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, who resigned from Parliament 18 months before he led the Afrikaner delegation to Dakar. He didn’t see it possible to change the system from the inside any more.

Anti-apartheid cleric Beyers Naude said in the film said that white people who openly opposed apartheid were ostracised from their communities.

At the end of the film he’s shown addressing a United Democratic Front (celebrating its 35th birthday this week, incidentally) meeting, saying once white people have paid this price, they’d find a bigger reward.

“You will make the astonishing discovery that the black community in South Africa will stand with open arms, and they will welcome you,” he said. At the time it was politically significant, but today it might sound naïve as white people are criticised for not being seen to return this goodwill.

Some of those who went on the Dakar trip lost their jobs, like counsellor Trudie de Ridder, who was called a “political terrorist” by her state employer.

Many of the interviewees were emotional, like ANC cultural head in exile at the time, Barbara Masakela, on Gorée Island.

Thabo Mbeki, centre, Steve Tshwete, right.

“People were taken away from their home forever and ever,” she said, but the ANC’s struggle meant “we will never allow ourselves to be a people who will succumb to slavery in any way or form”. Masekela was supposed to have attended the Johannesburg film screening, but her health didn’t allow. She was, incidentally, one of those who complained about the lack of female delegates in both the ANC and the white delegation at the time, said actress Grethe Fox, who was also in Dakar, during the post-film discussion.

Former medical doctor Jacques Kriel was so overcome with emotion in the film he could hardly talk. Tears running down his face, he voiced the uncertainties Afrikaner delegates faced upon their return home from Senegal.

“For us at the moment it’s not easy,” he said. Referring to the violence the apartheid government meted out to especially black opponents, he said: “I’m not worried about physical things that they do, I’m worried about how are they (back home) are being flooded with mis-propaganda interpreting our actions. How we have got to re-educate and take our families with us as people – and that for me is the major problem.”

Listening to his interview brought back that time so vividly, I was overcome by a rare bout of tears too. White opponents of apartheid suffered fewer physical attacks than black activists, but I recall our family being branded misfits by a small-minded community so ensconced in their comforts and so brainwashed by a heavily censored media that they hardly knew better.

Lourens du Plessis (Daily Maverick reporter Carien du Plessis’s father), left.

That there’s much more grey in South Africa’s politics today, was evident in the discussion after the film. A middle-aged black audience member said: “I felt very sad because the issues that these guys were raising (in the film), they are still with us today. South Africa remains a very divided society.” Referring to Kriel’s interview about apartheid’s psychological damage, he said: “I found it very sad that young South Africans who are white, I think they are still very much scarred” and don’t feel part of the country.

“I think not enough is done on the family level to have Dakar kind of discussions.” It was also sad that the ANC government still had a hard time convincing white people “that (black people) are not going to drive them into the sea, we are not a crazy people”.

Ilse Naude, Beyers Naude, centre, the late film director Manie van Rensburg, right.

He said President Cyril Ramaphosa still had to explain this to organisations like the Afrikanerbond, while Max du Preez “every day on News24” wrote columns explaining the ANC government “to white people” but also holding the government to account.

Another one said that while Germans made an effort to remember the wrongs in their history by educating their children about the Holocaust, in South Africa “we cannot mention apartheid because it makes some people uncomfortable”.

A white 33-year-old, who nine years ago encountered a black person as an equal for the first time, stood up and said white South Africans faced a “crisis of ignorance”. (Yes, this, after 24 years of democracy, and even though we have an uncensored media digitally on tap now, and 24-hour radio and television.)

Leon Wessels, a former apartheid minister who went on to serve in the South African Human Rights Commission, said a lesson from the negotiated settlement was that both sides were “seriously listening to each other because failure wasn’t an option”. Inter-generational discussions should happen with that same intensity, he said. “To a large extent I think we are not listening. There are many apartheid ghosts still drifting around.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider