South Africa

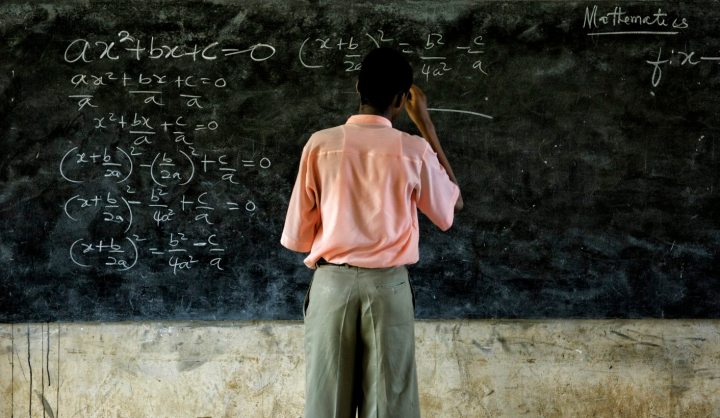

School maths: What is Our Story?

The South African school maths story is well known: Our school maths performance is very poor. We are second from the bottom of the international league table, and perform worse than some fellow African countries which spend less than we do on education. Despite 22 years of investment our matric maths pass rates are not improving. Yet our Minister of Basic Education asserts that we have a “system that is on the rise”. Is that just spin? What is our school maths story? By NICKY ROBERTS.

Maths is the subject most vulnerable to challenges in the school system. Like a caged canary in a mine, we watch it closely to reflect on the toxicity or health of our schooling system. Our South African school maths story is well known. It goes something like this:

Our school maths performance is very poor and unequal. Former apartheid Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd (when responsible for education) famously said that there was no place for mathematics in the education of the African child. They were to be “hewers of wood and drawers of water”.

We inherited a highly unequal system of education as a result of our colonial and apartheid past. This impacts on who can access mathematics, and has influenced who is capable of teaching it. Post-apartheid we have tried to create a more equal education system where all South Africans can access maths. But both improving educational quality and reducing educational inequality remain challenges. In maths, we perform second from the bottom of the international league table of 25 countries (just above Saudia Arabia). We are worse than Egypt, Botswana and Morocco who spend less than we do on education. We have prioritised mathematics as a subject for 22 years. However, there has been no impact on our mathematics matric pass rates.

The knowledgeable storyteller may explain what underlies this tale in many ways:

- Outcomes-based education was a mistake. Teachers did not know what mathematics to teach when.

- Teachers lack knowledge for teaching mathematics.

- Our schooling culture is exam-focused and perverse attention is given to one high-stakes exit exam (at Grade 12).

- We don’t have accountability systems.

- We lack resources (textbooks or classrooms or teachers…).

- Problems in maths are a direct result of problems in language.

- Problems in maths are evident from the early grades in primary schools and are compounded as learners progress through school.

- The children are not learning basic mathematics facts – they use very long, inefficient methods to perform calculations with larger numbers.

- There is inadequate coverage of the curriculum – teachers do not cover what they are meant to, with too little mathematics done each day.

- While some blame teachers’ low expectations (noting a lack of sufficiently challenging maths each day), others complain that the maths curriculum is too dense and too challenging.

- Sometimes trade unions loom large as a major bogeyman to spice up the story.

This familiar tale is retold from year to year; with a particular frenetic narration each January with the release of the matric results. This is so because, as for many good stories, parts of it are/were true.

When releasing the National Senior Certificate (NSC) results on January 4, 2017, Minister Moshekga referred to a “system on the rise”, and “a system in an upward trajectory”. Some dismiss this simply as spin. After all, improving the proportion of mathematics passes at Grade 12 level from one year to the next cannot be used as evidence of systemic improvement. Umalusi, our quality assurance body, has identified Grade 12 mathematics pass rates as worryingly stagnant.

So is there a case of improvement in South African school maths? Yes – I think so. In 2017, I think that we now have several rays of hope which question the basic plot of our story:

Ray 1: We are not in denial and we have a fairly detailed plan.

We know our school maths story and spend time trying to account for and change it. We have a detailed diagnostic report as part of our National Development Plan, and more detail is provided in Basic Education and provincial plans. Approaches to improving language and mathematics are being tested by more affluent and urban provinces, and in poorer provinces various interventions through the National Education Collaborative Trust (NECT) are being tested. However, more detail on how to improve mathematics from Grade R to 12, and greater coherence across provinces, is needed.

Ray 2: We are starting to gather and use evidence for systemic change

There have been numerous interventions involving school mathematics at a large scale. The methods used in these interventions are still being debated. There is much still to learn from and share.

Ray 3: Our maths teacher education system is growing and improving

We have systems to encourage ongoing professional development for our teachers already in schools. These are not without problems; but there is a growing – and accredited – suite of formal courses. Some of these programmes are being developed and refined through universities and the work of the National Research Fund Numeracy/Mathematics chairs. Some of these programmes are being offered, developed and encouraged by teacher unions and NGOs. The Department of Higher Education is leading an EU-funded programme to further improve initial teacher education for primary teachers. We have an indication that our teacher education system is improving. From our regional benchmark (Southern and East African Consortium for Monitoring Education Quality – SAQMEC IV) teachers (at Grade 6 level) who were trained through university programmes performed better in a mathematics test than older teachers who were not trained in this way. We require more data to confirm this finding and establish whether this holds for teachers at other Grade levels. More is required to monitor and improve both initial and ongoing teacher development.

Ray 4: We know that targeting matric maths (or even Grades 10-12) is too little, too late

We know that a lot of investment was wasted on targeting the school exit point (Grade 12). From 2011 to 2014 we got common assessment data on maths (from the Annual National Assessments in Grades 1-7 and Grade 9 levels). This showed that maths problems occur from early on, with problems at Grade 6 seriously compounded by Grade 9. There is now at least more talk about intervening and supporting maths from the earlier grades.

Ray 5: We are finding ways to get meaningful data from earlier Grades

How Annual National Assessment (ANA) data was being used was a concern to teacher unions. As a result the ANAs were not administered in 2015 and 2016. Useful assessments communicate about standards, set high expectations and support diagnosis and remediation. As such, a collaborative process involving the state and teacher unions is under way to plan how assessments can be meaningfully designed and utilised. South Africans should expect to get national assessment data (at Grades 3, 6, and 9 to complement Grade 12) in 2017.

Ray 6: We are starting to report on retention

Reporting solely on pass rates, we neglect those who are no longer in the schooling system. This year the Department of Basic Education reported on retention rates (how many people are staying in the school system) up to age 15, together with the NSC results. This is to be welcomed. One of the provinces also reported on its retention of older learners (in Grades 10-12). South Africans should expect annual reports on retention rates alongside pass rates (at Grades 3, 6, 9 and 12 levels).

Ray 7: We know we must invest in early childhood development and improve the quality of Grade R and primary maths

International research indicates that it is most cost-effective and educationally effective to invest early on, and that this is also a major lever for reducing inequality. We have successfully expanded access to free public Grade R; and are aware of the need to improve the quality of this (especially in rural provinces). Currently one of our more urban provinces is trialling a mathematics professional development intervention, and mathematics materials for Grade R teachers. There is far more to be done to improve maths in all of primary school. Far more is need at the Early Childhood Development level and to join up health and social services with schooling.

Ray 8: We know improving maths results involves all of us

We know that success in maths cannot be divorced from success in language and literacy. We know that teachers of maths (from Grade R to Grade 12) are pivotal and require ongoing, long-term professional support to improve both their knowledge of maths and of how children learn maths. Along side this we know that school leaders, and subject advisors at district level, can play an important instructional leadership role. We know that parents and caring adults can help and that after-school maths clubs, family maths days and homework drives yield improvements. Far more is needed to ensure that learners themselves experience maths as something that makes sense. Maths results improve when learners and teachers believe that they are capable of learning and explaining maths, and when they all work hard and think hard to solve difficult problems every day.

Our maths story is not yet complete, and much remains to be done. However (and this is the real plot changer) two sets of independent, benchmark tests show that we are improving in maths.

First, our regional benchmark assessment (Southern and East African Consortium for Monitoring Education Quality – SAQMEC IV), conducted in 2013, shows that at Grade 6 level we are performing better in mathematics than in the two previous studies. We are now above the 500-point “centre point” (which considers the 15 other member countries on our continent).

Second, in our international benchmark mathematics assessment (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study – TIMSS), when we compare Grade 9 performance in TIMSS 2003 to TIMSS 2015, South Africa improved more than for any other country with comparable data. This was equivalent to an improvement in performance of approximately two grades. Yes, we are still in 24th place, but we can’t expect better than “most improved”. (With our improvement sustained over the three studies.)

Looking at each ray individually, there is still much room for improvement. Taking the eight rays together, and combining them with the two sets of independent benchmark data, it is clear that (1) our school maths needle is no longer static and (2) the needle is moving in the right direction. We are not yet writing a completely new school maths story, but in 2017 (at last) our tale is indeed changing for the better. DM

Photo: World Bank Photo Library.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider