Maverick Life

Madiba’s Song: Opera and the state in the new South Africa

After watching the latest stage work about the life and times of Nelson Mandela, J. BROOKS SPECTOR contemplates the place of opera in today’s South Africa.

Way back in those supposedly halcyon days of the Apartheid state, opera (along with ballet) was purposely used to prove the importance and vitality of European high culture right at the southern tip of Africa, thousands of kilometres from its presumed spiritual home, way to the North. As South Africa’s cultural isolation took hold with a vengeance from the late 1970s, it became even more imperative to Apartheid’s cultural commissars to make the case to an increasingly worried population that South Africa’s segregated culture was still strong, was still safe, and, most importantly, perhaps, was still white.

Then, as the old regime finally collapsed in the 1990s, its long-time cultural critics, arguing for support for a new and increasingly authentic South African culture, took out their ire on the relics of the old regime. While there were no tumbrils or guillotines providing an ultimate dramatic ending to Apartheid-era cultural leaders (or pretty much anybody else), the new cultural nomenklatura aimed for the bureaucratic equivalent. They decried opera, ballet and most other classical performing arts as hopelessly Eurocentric, worthy only of being cut off at the financial knees. In succeeding years, the PACT (Performing Arts Council of the Transvaal) opera program was wound down, the ballet company likewise. Behind these choices was the idea that a new country deserved a new cultural universe – and the old ways of doing grand opera would not be part of it.

Of course things were never quite as simple and clear-cut as the old Apartheid regime – or the new authorities – made it out to be – or wanted it to become. For example, the Eoan Group, a Coloured music and dance ensemble based in Cape Town, regularly produced full-scale operas and ballets, even, on occasion, touring to Johannesburg with a clutch of full-scale operas performed in repertoire in one tour. It continued performing until political and financial vicissitudes effectively wound down most of its activities by the 1970s.

And until Apartheid strictures finally put an end to them as well, there were regular seasonal performances of works like Handel’s Messiah with thoroughly integrated casts in Johannesburg (although audiences were segregated at alternate evenings). Up through the present, black choral groups have routinely included excerpts from the most popular grand operas and oratorios, together with traditional hymns and secular choral works.

But an intriguing paradox in South Africa, even as opera was being effectively denigrated as un-African and retrograde politically, an entire generation of gifted young singers, most recently including such stunners as Pretty Yende and Kelebogile Boikanyo, were finding their way to the operatic repertoire, and then on to serious training in the opera programmes at universities, even if their professional futures were problematic. Meanwhile, in spite of official reluctance to embrace opera in funding terms, several entrepreneurial cultural organisers began producing operas in the country’s major cities – and even commissioning some new works.

Most notably, after its debut in South Africa, Mzilikazi Khumalo’s Princess Magogo has been performed abroad and – after several rewrites – is probably South Africa’s best-known locally written opera. Drawn from the true story of a daughter of a Zulu king who was ordered to compose her music in order to rally a conquered, shattered society, thereby surrendering her desires for love and a family, the work made use of more usual operatic conventions as well as inspiration from Magogo’s actual compositions.

From its enthusiastic reception in South Africa as well as a favourable reception at Chicago’s Ravinia Festival, Khumalo’s opera (orchestrated by others) seems to have led the way for a rethink for South African officialdom – and a real volte-face about the uses of opera in the battle to sculpt a new nation. No longer just for those Eurocentric wannabes, opera was now a tool to demonstrate that the new South Africa could play in the cultural big leagues – that this so-called provincial nation could also do the operatic dance. Khumalo’s Princess Magogo has been followed by a work like Phelelani Mnomiya’s Ziyankomo and the Forbidden Fruit, offering an entire opera in isiZulu as part of the national project.

In one sense, this growing embrace of opera has meant that South Africa was now recapitulating some of the ways opera evolved in Europe and America during the past century and a half. Sponsors with big pockets vied for supporting expensive productions in increasingly lavish venues – and as the most talented singers became popular entertainment stars. Increasingly, too, operas were composed along nationalist themes – often drawing upon the recognisably indigenous music of the respective countries of the composers. And now in South Africa, quite suddenly, not one but four new operas have been written about the late Nelson Mandela – or Winnie.

The first of was the Cape Town Opera’s three-co-composers work, The Mandela Trilogy.

A second was Bongani Ndodana-Breen’s Winnie.

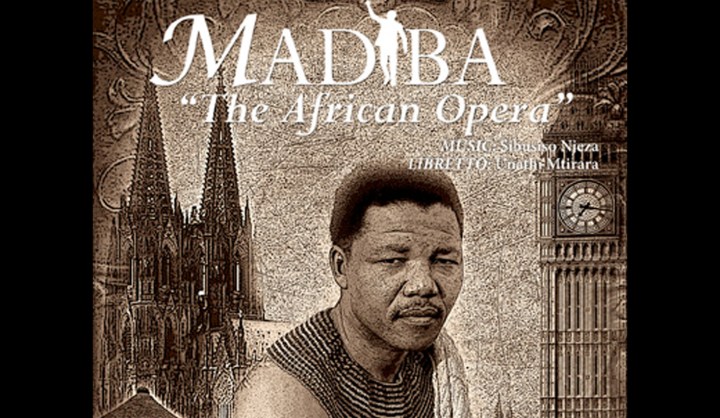

And a third work, Madiba – the African Opera, composed by the young composer, Sibusiso Njeza, to a libretto by Unathi Mtirara, with orchestration by Kutlwano Masote, has just received its premiere in Pretoria on the evening before Jacob Zuma’s second presidential inauguration. The large, mostly young cast features Thabang Senekal as the adult Madiba, Sibongile Mngoma as Winnie Mandela, Zandile Gwebityala-Mzazi as Zinzi Mandela, Kabelo Lebyana as King Jongintaba, Sipho Fubesi as Justice Mtirara, and Bongiwe Nakane as Evelyn Mase, among numerous others, with conducting honours shared between Kotlwano Masote and Robert Maxym. The Kupano Chorus gets several large-scale ensemble opportunities in this work as well.

Finally, a fourth work, this one composed by the musically eclectic Neo Muyanga, is scheduled to open later in 2014 as well.

Not surprisingly, taking on a globally iconic figure like Nelson Mandela, let alone the still-living Winnie Madikazela-Mandela, and turning them into characters in an opera is a tough task to carry off with ease. The possible pitfalls of this same challenge have been evident in live theatre works dealing with Mandela such as Aubrey Sekhabi’s The Rivonia Trial, as well as in the various made-for-TV and big screen films on the same life, including the recently released, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom.

In all of these works, in creating the narrative, the almost inevitable solution is to elide around a deeper exploration of the dramatic tensions, fears, and intrigues that are the meat and potatoes of an opera, or a good bio-pic. This clearly becomes harder to do when the writer or composer tackles the life of someone regarded with religious near-reverence by many in South Africa – and well beyond. Perhaps it is just simply too early to gain the kind of historical perspective than can effectively inform a serious musical work.

Yes, historically, of course, opera composers have frequently tackled political themes or put real, historical figures in their works. For example, Guiseppi Verdi, in an opera like Rigoletto drew upon Italy’s bloody history to propagandise for its regeneration and unification as a single nation – even though he used a story drawn from hundreds of years before his own time as the opera’s setting. Other nationalist composers like Alexander Borodin drew upon the actual historical Prince Igor for his great opera of Russian nationalism. And in a more risky way, a contemporary composer like John Adams drew on US President Richard Nixon’s visit to China (a work that included Chao En-Lai, Mao Zhedong and Henry Kissinger), and the violent takeover of the cruise ship, the Achille Lauro, by the PLO and the killing of one of its passengers, as raw material for two of his best-known works.

But a crucial element for any of these works is that the operatic composer must build conflict and drama into his work. A hero, a heroine, or villain must somehow be torn between two loves; between cowardice and dangerous, even foolhardy, bravery; or between loyalties to family or broader principles. And the music must elaborate and illustrate these tensions in sonic terms. The challenge for an opera constructed around the life and loves of Madiba has, so far, been the quite natural reluctance of composers and librettists to build weaknesses and indecision into the portrayal of a hero like Nelson Mandela; or to build an arc of dramatic tension that can only be resolved by a decisive act of love, commitment to cause and principle, or by death. Perhaps it is just still too early to allow an all-too-fallible Mandela to exhibit an all-too-human character on stage where he is torn by his commitment to duty, even as he is pulled towards family; for his affections to be split between two women; or, finally, to put his dedication to his liberation cause above his own or his family’s real needs and desires.

Librettist Unathi Mtirara, himself a member of the Tembu royal family, was understandably eager to offer audiences a fuller, richer historical portrait of Nelson Mandela than is usually on view. As a result, he devotes the first act to placing Mandela in the challenges of a royal family in the throes of confronting the modern order. He traces the life of a child removed early from his mother’s care, who is then sent to live with a distant royal relative, and who then must go on to boarding schools to groom him for his adult destiny as an advisor to a future Tembu king. This story moves forward at a stately pace, until, eventually, years later, the now-young adult Mandela rebels against this destiny and secretly flees, together with a cousin, on to Johannesburg for an independent life in defiance of the king’s orders.

In the second act, Mandela then moves through his second marriage, the Kliptown meeting that adopts the Freedom Charter, his arrest and the subsequent Rivonia Trial, the long years of imprisonment, the Wembley Stadium “Free Mandela” concert (including a Brenda Fassie who didn’t actually sing there), his release from incarceration, and then on to the oath of office as the country’s first democratically elected president – as the cast and audience all rise to sing the new combined national anthem. That is a lot of ground to cover in one evening – in quick tableau after tableau – but the result doesn’t leave all that much space for the dramatic collisions that will make people sit up and take notice – and wonder or marvel how it will all work itself out musically.

But beyond the question of building momentum via drama and conveying it via the music, there is also the big question of how to create music that will bring unify the elements of a story to be told. In a work like Princess Magogo, Mzilikazi Khumalo mined the traditional South African indigenous music he knew so well, but he thoroughly reworked just such resources in orchestral and western vocal terms. As a composer, Njeza seems to have approached this task rather differently. In his Madiba, he brought together musical elements that sometimes recall the Handel anthems and choruses so frequently sung by African choirs, to composing music that flirts with those complicated, involved, 20th century classical musical ideas, as well as traditional tribal chants and dances. And, of course, there is an extended nod or two to the iconic pop music of the period.

But an opera must be more than just the stringing together of a range of newly composed music and musical ideas, and wide-ranging musical influences. The music must paint the characters’ emotions with colours beyond what can be said or sung in words by the characters on stage. The music must serve as a mirror of the souls of the characters.

Opera is an expensive, financially complicated habit for a government to take on, of course. Now that South Africa’s government has gone into the business of underwriting and sponsoring the occasional opera as a kind of national building project, a real task is to figure out how to nurture the skills of composers who can grasp what is needed to deliver works that explore the fullest range of the country’s stories – beyond simply the continued mining of Madiba magic. Concurrently, composers must deliver works that speak to contemporary feelings about the country’s musical heritage – even as they embrace the dramatic needs of this unique art form. Finally, groups trying to produce such operatic works must get the sustainable support that will allow them to put to work the country’s many fine operatic voices – singers who, now, far too often, must go abroad to Europe or America in order to find continuing artistic challenges and work.

The Cape Town Opera, for example, has found that it generates much of its operating budget from the revenues of its overseas touring, rather than via sufficient financial support at home. Other companies are struggling even more. But surely there must be a way to lure the country’s new voices back home for regular seasons and performances, thereby entertaining audiences and inspiring new singers with the potentials and challenges of their own careers – and, simultaneously, giving composers a reason to continue growing as artistic creators.

Perhaps most important of all, the country also needs a much better way to educate its young people into enjoying and appreciating the operatic repertoire – overcoming the feeling that this is music for the swells, the rich and the foreigners. But that, of course, leads on to the sorry quagmire of arts and culture education in the country more generally.

While a national arts curriculum exists on paper, the actual teaching of the arts – whether music, art, drama or dance – is a fiction for the vast majority of the country’s schools and students these days. There is little effort to bring the works of professional companies and performers to the attention of most of the students across the country – or for students to even imagine that these disciplines may be a way to find a job and a career.

The sector can, with some nurturing, be a place that can actually create real jobs. But without real educational efforts, the country may never generate the demand for the arts sufficient to sustain performers and companies over the longer-term, and giving government agencies and businesses real reasons to improve their support for the arts – including opera, along with all the rest of the possible cultural choices. Instead, the arts and arts organisations will be condemned to remain a minority taste for a minority of the country’s people. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider