OBITUARY

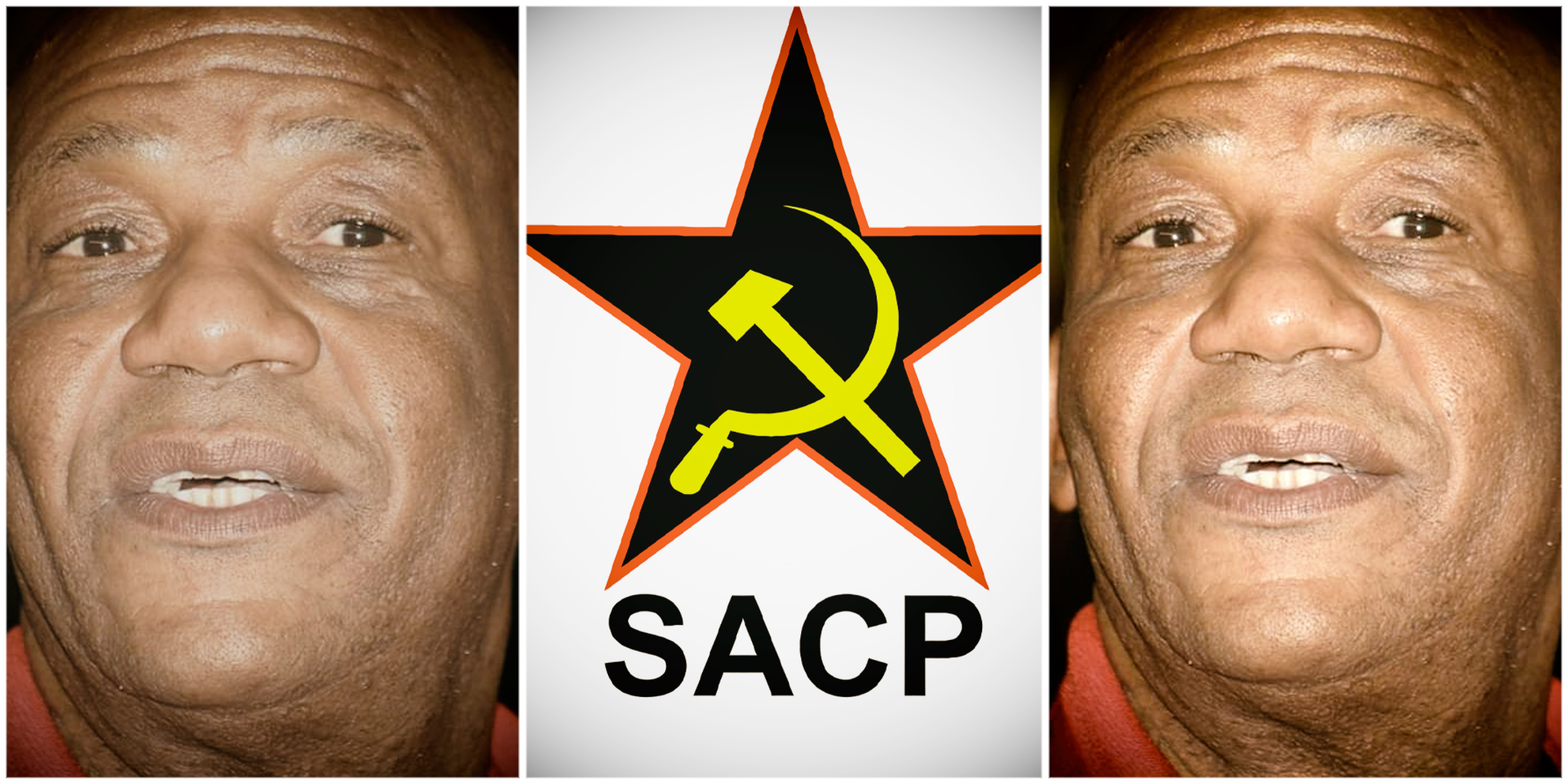

Chris Matlhako – an SACP stalwart and Young Turk forged in the ‘fire and ash’ of the student struggle

His differing views within the South African Communist Party notwithstanding, Matlhako had appeal across all factions of the party, with a natural instinct to find consensus solutions.

Chris “Che” Matlhako, former second deputy general of the South African Communist Party, was known in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a “klipgooier” (stone-thrower) at the University of the Western Cape, as he was always among the first comrades out to confront the police during anti-apartheid demonstrations.

When we first met, he had his then characteristic basketball cap turned upward, seemingly permanently planted on his head. I at first glance made the mistake, I suspected many made at the time, of confusing his “klipgooier” reputation for a youngster empty on content but high on rhetoric, slogans and militant action. However, Matlhako was a deep thinker. His natural instinct was to find consensus solutions. When in contemplation, considering a middle way to a problem, a deep frown would often sweep over his forehead. He was a highly pragmatic individual.

After an initially hesitant start, we developed a close friendship, forged initially in the editorial collective of the award-winning Student Voice, the student community newspaper of the University of the Western Cape. We spent many nights in the basement of the student centre, where the paper’s office was located, putting together the tabloid, in the old pre-technology cut-and-paste way.

Both of us secretly joined the SACP. I left after the end of formal apartheid, when I joined the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) as a staffer at its head office; and he stayed, rising to second deputy general secretary of the SACP in 2017.

Both of us as youths supported the Govan Mbeki and Harry Gwala axis within the ANC’s Robben Island Prison leadership, who represented the ANC Left, and who often challenged the centrist Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu leadership during their lengthy incarceration there. After I was granted a prized interview with Gwala on his release from Robben Island, Matlhako bombarded me with questions for months afterwards, wanting to know every detail of the views of the “Lion of the Midlands” on every aspect of ANC politics.

Matlhako, hailing from small-town Kimberley, was surprisingly not parochial, but a strong internationalist. We both shared an admiration for the Cuban struggle to build an equitable society in the post-World War 2 period. Both of us got involved in the early Friends of Cuba Society South Africa (FOCUS). I moved on, and he would later become the secretary of the organisation. At his passing FOCUS stated that “not many comrades can claim to have had such a great impact on the bilateral programme” between Cuba and South Africa “as comrade Chris did”.

Both of us, like many of the 1980s generation, were enthralled with the writings of the late Nobleman “Mzala” Nxumalo, a towering black intellectual, who wrote the 1988 book Gatsha Buthelezi: Chief with a Double Agenda. It caused a sensation when it was released, was banned at many universities – and was taken off university library shelves. Such was Matlhako’s admiration for Nxumalo that he wrote under the pseudonym “Mzala” in Student Voice, and other student press publications.

Mathlako was a non-racialist, and a believer that a common South Africanness must be woven around our diversity.

Matlhako completed a degree in politics and history at UWC, before doing a master’s in politics at the University of the Free State, examining provincial state-building in the Northern Cape under the ANC government. Before his passing I had introduced him to colleagues at the School of Governance at the University of the Witwatersrand, to potentially supervise him on a doctorate he was keen to pursue.

A collection of his articles was serialised in the magazine Thinking Che, with the first volume appearing in 2019.

After university, Matlhako returned to his hometown, Kimberley, immersing himself in building the provincial structures of the SACP, and becoming the party’s Northern Cape secretary. He was later elected to the central committee of the SACP and became its international secretary – the international face of South Africa in the international communist movement. His geniality, warm personality and sincerity won him friends wherever he went.

Roots

Matlhako grew up in the Galeshewe township in Kimberley. He attended St Boniface Boys’ High School in the early 1980s, a Christian Brothers’ college. The school was run by Brother Donald Madden, an Irish Jesuit and a formidable moral educationist. Thebe Ikalafeng, the former head of Nike Africa, who also attended the school, says Madden was a strict disciplinarian who did not only care about pupils performing academically, but prioritised their overall well-being with equal dedication.

Matlhako cut his teeth in the 1980s youth uprisings. Although the Congress of South African Students (Cosas) was formed in 1979 by Black Consciousness-aligned leaders in response to the 1976 onslaught against anti-apartheid youth activists, the organisation changed dramatically in the early 1980s, when it was taken over by congress-aligned pupils.

In February 1980, a new wave of high school protests erupted, starting this time on the Cape Flats, initially among predominantly coloured schools, followed by Indian schools, before it engulfed all black schools across the country. A new generation of high school pupils had now entered what would become the most violent, deadly and destructive end-phase of the struggle.

Read more in Daily Maverick: The ‘New Struggle’: An alliance of high-calibre leaders is needed to craft a better future for SA

The change in Cosas started when the Cape schools embarked on a three-month boycott of classes, from February 1980 to July 1980, demanding equality of state support for black education, for the right to have student representative councils and for run-down schools to be fixed. More than 30 pupils died in the police response to the boycott.

Cosas was put on a fundamental new path when, in 1982, it resolved for pupils at high school to partner with workers in joint struggles beyond the classroom. Student-worker action groups were encouraged, where pupils became actively involved in community struggles, such as fighting high public transport costs, for consumer rights and tackling local crime, as well as to support workers in their demands for better wages.

This almost immediately made us youth activists more conscious of real-life issues, beyond the limitation of school educational politics, and compelled many to get involved in wider community-based service delivery protests, human rights campaigns and trade union struggles. Cosas aligned itself with the United Democratic Front in 1984. Matlhako, like many of the 1980s high school-generation activists, was influenced by this new Cosas.

On 14 February 1984, 15-year-old pupil Emma Sathekge, from DH Peta High School, was killed and scores were injured when police clashed with protesting Atteridgeville high school pupils over their demands for an end to corporate punishment, to allow overage pupils who had failed exams back to school and for the right to establish student representative councils. Sathekge’s death became a lightning rod for protests which, from February until November 1984, swept across the country, which focused on broader societal grievances, not only against inferior education for blacks, but also against rent hikes, the presence of the security forces in townships and unemployment.

For our generation of school pupil activists, 1985 was a year of “fire and ash”. The anniversary of Sathekge’s death on 14 February 1985 sparked new levels of high school protests across the country. Soon thereafter, pupils closed down many black schools across the country to start the longest school boycott in South African history, which would last for many schools until 1988, sparking the phenomenon of the “lost generation”, thousands of young people who did not receive any formal schooling for years.

In Galeshewe, Matlhako was a prominent figure in both the Galeshewe Youth Organisation (GAYO) – which included non-school youth, including the unemployed and Galeshewe Students Organisations (GASO), which was the umbrella organisation of students in the township. Phemelo Sediti, who also attended St Boniface, and is now involved in the Galeshewe Theatre Organisation, remembers fondly how he was recruited by Matlhako to join GAYO and GASO in 1985.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Young, Gifted, Black and still left behind: South Africa’s youth struggle continues 45 years later

Sediti said he had his political awakening following the brutal shooting by riot police on 11 April 1985 of youth activist Tommy Mmereki Morebodi during anti-government protests in Galeshewe. His shooting unleashed violent conflict in the area. Thousands flocked to his funeral. Police shot live ammunition at the march following the funeral, and arrested dozens of protesters. Street resistance continued between July and October 2023.

He was not an old-style SACP communist. He was a democratic socialist, along the lines of the now modernised post-Cold War Western Eurocommunist parties.

Matlhako was detained for 10 days in Kimberley, starting on 10 April 1985. The riot police had swooped on known youth activists in Galeshewe, and Matlhako was identified as a key youth leader in the area to be silenced. He was brutally tortured and spent a long time in hospital. He never talked about it afterwards, but the physical and mental impact of that police torture lingered long after the event. Matlhako died on 20 April 2023, on the anniversary of the day he was released from that brutal detention.

Humble, tolerant

Mathlako was a non-racialist, and a believer that a common South Africanness must be woven around our diversity. He was tolerant of different opinions and had friends from across the ideological spectrum and across the colour line, at a time in the 1980s when there were strong camps in the anti-apartheid youth and student movements, with violent battles between those of the congress tradition and those from the Black Consciousness movement and Inkatha.

He was humble, often apparently self-effacing, and at ease with people from backgrounds dissimilar to his. Julian Jacobs, former news editor of Student Voice and now lecturing journalism at Rhodes University, remembered Matlhako’s wonderful sense of humour.

Matlhako was part of the Young Turks within the SACP, opposed to the party embracing former Jacob Zuma for the ANC presidency at the ANC’s 2007 Polokwane conference. Most of the Young Turks, such as Langa Zitha and Viswas Sathgar, were expelled from the SACP by the pro-Zuma leadership. However, Matlhako survived, largely because he was seen as someone who, despite his differing views, was a unifier, with appeal across all factions of the SACP.

Matlhako was elected by the SACP grassroots members as second deputy general secretary at the party’s 2017 elective conference, despite the fierce opposition of the old guard of the party – which had supported Zuma for ANC president in 2009, and which was led by long-standing SACP general secretary Blade Nzimande.

Zuma’s “nine wasted” years in government, in the end, proved right those members who opposed the SACP support for him. Because of his non-factionalist approach, Matlhako often defended those who fell afoul of the party leadership because of differing views. Castro Ngobese, one of the Young Turks who narrowly survived being purged by the SACP leadership, but for the intervention of Matlhako, said upon his passing: “Thank you for standing up for some of us when a dominant Stalinist faction wanted us out in the Party.”

Matlhako was also a proponent of the SACP going it alone in elections, as an independent party, and for the party to form an alliance with the ANC after an election, based on the number of votes the SACP would get. The expulsion of some of the SACP’s great talent over the party’s support for Zuma possibly damaged the party to such an extent that as the ANC declines, it may be too damaged to become a major independent political force. The SACP has come to be seen as indistinguishable from the ANC – and it will fall with the ANC, when the ANC loses power.

Matlhako’s increasingly ill-health since 2019, combined with his continued insistence that the SACP should prepare to stand independently in the coming elections, the dominant faction of the party, which had supported Zuma and was in favour of the SACP continuing the current configuration of its alliance with the ANC, campaigned to block Matlhako’s re-election as second deputy general secretary at the party’s elective conference in 2022. Matlhako was re-elected as international secretary.

He was not an old-style SACP communist. He was a democratic socialist, along the lines of the now modernised post-Cold War Western Eurocommunist parties. He views were akin to those of the Italian Democratic Party, the former Italian Communist Party, which renamed itself, initially in 1991 as the Democratic Party of the Left, and in 1998 as the Democrats of the Left, and finally when it merged with the left-of-centre Daisy (Margherita) party, to consolidate all the different progressive left groupings in Italy to form the Democratic Party.

The SACP, for its own survival, will have to modernise, ditch its Marxist-Leninist doctrine, and adopt a broader Left democratic programme, and try to bring together in a broad front of the small progressive left groups and willing trade unions, just like the Italian Communist Party did, and stand on its own in next year’s national election. If not, the SACP will, when the ANC loses power, become an insignificant relic of the past. DM

William Gumede was former editor of the award-winning Student Voice newspaper and former head of the South African Students’ News Agency (Sasnews).

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.