Africa

Africa’s First President for Life Turns 120: The bequests of Liberia’s William Tubman

William Tubman governed Liberia during the most formative years of its current President, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, from the age of six to 33. The trappings of office that he enjoyed and the numerous properties he acquired from humble origins incentivised future Liberian autocrats and warlords to pursue power by any means. By BROOKS MARMON.

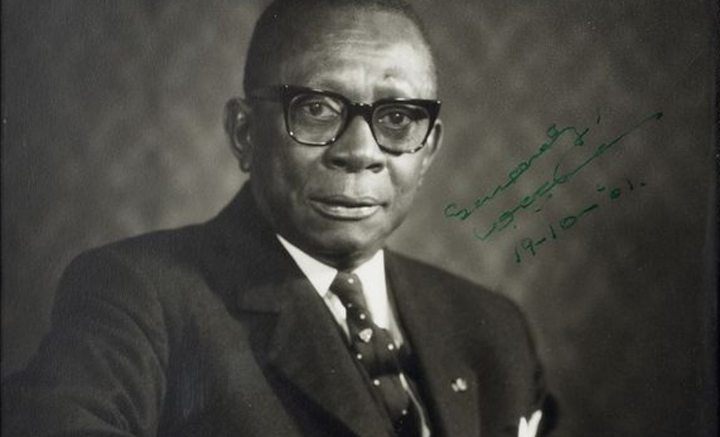

Photo of William Tubman by JFK Library.

Throughout its first century of existence, Africa’s oldest republic enjoyed an almost uninterrupted succession of smooth transfers of executive power. When Liberia turned 100 in 1947, under the administration of William VS Tubman, its longest serving leader was its immediate past president, Edwin Barclay, who held office for 13 years. As the Cold War intensified and Africa decolonised, Tubman tightened his grip over Liberia. His name continues to dominate the nation’s political sphere, long after his death in 1971 ended a 27-year reign.

The main thoroughfare of Monrovia, the nation’s capital, bears his name, several statues and busts grace the University of Liberia campus, and the busiest intersection in Monrovia is home to a monument erected in his honour. His birthday, November 29, is celebrated as a national holiday. This legacy seemed unlikely when Tubman first came into office.

Born near the Ivorian border, far from the capital, his nephew, Winston Tubman, a prominent opposition politician who finished second in the last Presidential elections notes, “he was not one of the establishment people, he was an outsider.”

Tubman did not graduate from high school, but as a US State Department brief following his election noted he was “gifted with a quick mind [and] keen intuition.” Togba Wreh, the son of one of Tubman’s greatest antagonists, the writer Tuan Wreh, calls the President a “tyrant” but adds that “Tubman was a born politician that knew how to play his cards… people used to like him and fear him.”

Tubman’s lengthy term in office necessarily means that his leadership had an indelible impact on his successors, who have all been accused of autocratic tendencies. Liberia’s military ruler Samuel Doe, and the rebel leader, Charles Taylor, who displaced him, knew no other leader for the first two decades of their life. Tubman governed Liberia during the most formative years of its current President, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, from the age of six to 33. The trappings of office that he enjoyed and the numerous properties he acquired from humble origins incentivised future Liberian autocrats and warlords to pursue power by any means.

Former Finance, Minister Byron Tarr, notes that: “Tubman’s authoritarian behaviour remained a stimulus to sustaining the drivers of conflict.” However, C William Allen, Liberia’s Ambassador to Paris, urges contemporary observers “to evaluate his actions and inactions within the context of his contemporaries and the geopolitical realities of the era in which he lived.”

Tubman was born on 29 November 1895, when both the British and French imperial powers that bordered Liberia were gobbling up its land. In 1930, the Liberian President CDB King, a close ally of Tubman’s, was forced to resign following pressure from the League of Nations. This external influence undoubtedly shaped Tubman’s worldview. As he announced in 1965, Liberia’s “laws were disregarded with impunity by foreign nationals, her territorial sovereignty and integrity were time and again violated and in many instances her territory forcibly seized.”

American academics like J. Gus Liebenow criticized Tubman for not living up to the nation’s historic ideals as Africa decolonized. However, as the Cold War became hot, Tubman’s deference to the West harkened back to the “bitter, humiliating, and frustrating experiences” that he saw Liberia experience at the hands of outsiders. President Tubman assiduously courted the US, visiting numerous times and offering access to national facilities, such as the Robertsfield airport, a tactic mirrored by Sirleaf, who has been the only African head of state to offer the US a continental base for the Pentagon’s Africa command.

While Tubman did not adopt the radical stance of his contemporaries who came to power through popular protest, Ambassador Allen observes that Tubman was “in step with the winds of African nationalism in the post-WWII era.”

Tubman challenged the legality of apartheid South Africa’s administration of Namibia before the United Nations, and provided support to a number of African liberation figures, including Nelson Mandela. A 1959 meeting in Liberia with the heads of state of Ghana and Guinea served as a precursor to the formation of the Organization of African Unity, and Tubman was close to the ex-wife of the pan-African giant, Marcus Garvey. However, Tubman’s most pressing considerations were on the domestic front. Liberia was governed by a North American settler elite (Georgian in Tubman’s case). In addition to pressures from European powers, disgruntled Liberian indigenous groups threatened the nation’s existence.

Winston Tubman states that his uncle “was aware of these divisions. He felt like he needed to bring the country together.” Toward this end, Tubman appointed Momolu Dukuly, an ethnic Mandingo, as his Secretary of State, and often installed him as acting President when he travelled abroad. Winston adds that he believes President Tubman “would feel we haven’t made much progress in that area.” Earlier this year, Liberia was rocked by the suggestion of a constitutional review committee that the state should become a Christian nation, with President Sirleaf remaining silent on the issue for months before finally speaking against it.

Dr. Elwood Dunn, Minister of State for Presidential Affairs for William Tolbert, Tubman’s Vice-President and successor, critically notes that this Unification Policy “seemed progressive [but was] …essentially assimilation of one community into another, rather than two equal communities consolidating values.” Nine years after Tubman died in office, Tolbert was massacred in a coup and 13 senior government officials, many of whom had been trusted lieutenants of Tubman’s were subsequently tried and executed.

Winston Tubman admits that his uncle was a “strongman.” Tubman forced Didhwo Twe, an opponent in his first bid for re-election in 1951 into exile in Sierra Leone. When Tubman was challenged by Barclay in 1955 elections, he responded violently, and two prominent supporters of Barclay were killed in a gunfight. Future Liberian leaders would resort to much greater force, with Samuel Doe and Charles Taylor fighting viciously to maintain power.

The indigenous military government that followed Tolbert quickly became divided along ethnic lines. These were exacerbated by the outbreak of civil war in 1989, and linger today. President Sirleaf faces criticisms that she favours the old elite, with critics pointing to her appointment of a Minister of Agriculture who held the same position in 1979, at which time she promulgated unpopular policies that led to deadly riots.

Photo: Charles Taylor (EPA/STR), Samuel Kanyon Doe (Photo owned by Frank Hall), Current President of Liberia Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf speaks during the inauguration of the Women For Africa Foundation annual event celebrated in Madrid, Spain, 16 November 2015. EPA/JAVIER LIZON

Tubman’s most visible achievements were in the sphere of economic development. His Open Door Policy attracted a range of foreign investment eager to exploit Liberia’s natural resources in the post-war boom, most notably rubber and iron ore. Winston notes that at the time, Liberians “didn’t have the expertise – when we were doing a deal, we got a bad end, but part of his policy was to educate people so that we could get a better deal.” Unfortunately, despite Sirleaf’s success in attracting substantial debt relief, Monrovia was recently named the poorest city in the world. Liberians continue to express frustration with the terms of concession agreements, rioting and destroying the property of foreign corporations.

Tubman tightly controlled the treasury; his approval was needed for all significant government expenses. His extensive system of patronage was replicated, albeit much less successfully, by both the military and civilian leaders that followed him. Today, President Sirleaf demotes and shuffles Ministers around at will. She recently dismissed her Minister of Internal Affairs, a long-time confidante, with no explanation.

Another method that Tubman used to maintain his grip on power was tight control of the press. Writers and publishers like Albert Porte, STA Richards, and Tuan Wreh were harassed and jailed by Tubman. Liberian Presidents continue to enjoy an uneasy relationship with the local press, with even President Sirleaf, the Nobel Laureate, making the accusation earlier this month that local media is “undermining the economic potential and stability of our country.”

Winston Tubman stands by his uncle, calling him a “steady, consistent, [and] wise leader.” Notable segments of society maintain a nostalgia for the stability that prevailed in the Tubman era. Fiona Weeks, whose Grandfather was President of the University of Liberia at the time of Tubman’s death, states, “my views of Tubman have always been favourable.” She is particularly struck by historical images of Tubman’s capital which appear “almost futuristic when compared to the current state of Monrovia today.”

Nathaniel Barnes, a prominent former government official and a relative of Tubman’s via his maternal line, demurs, noting that the patronage system and the superficial economic growth over which he presided “created a perfect storm. The stage was set, whoever succeeded President Tubman had few options.”

More than four decades after his death, the greatest legacy of Tubman may be that Liberians, whether they embrace or reject their longest-serving President – their last to assume office in a constitutional transfer of power – are unable to escape from the core style of governance and leadership that he exerted in a bygone era. DM

Brooks Marmon is a Program Officer with the Accountability Lab in Monrovia.

Photo: Charles Taylor (EPA/STR), Samuel Kanyon Doe (Photo owned by Frank Hall), Current President of Liberia Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf speaks during the inauguration of the Women For Africa Foundation annual event celebrated in Madrid, Spain, 16 November 2015. EPA/JAVIER LIZON.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider