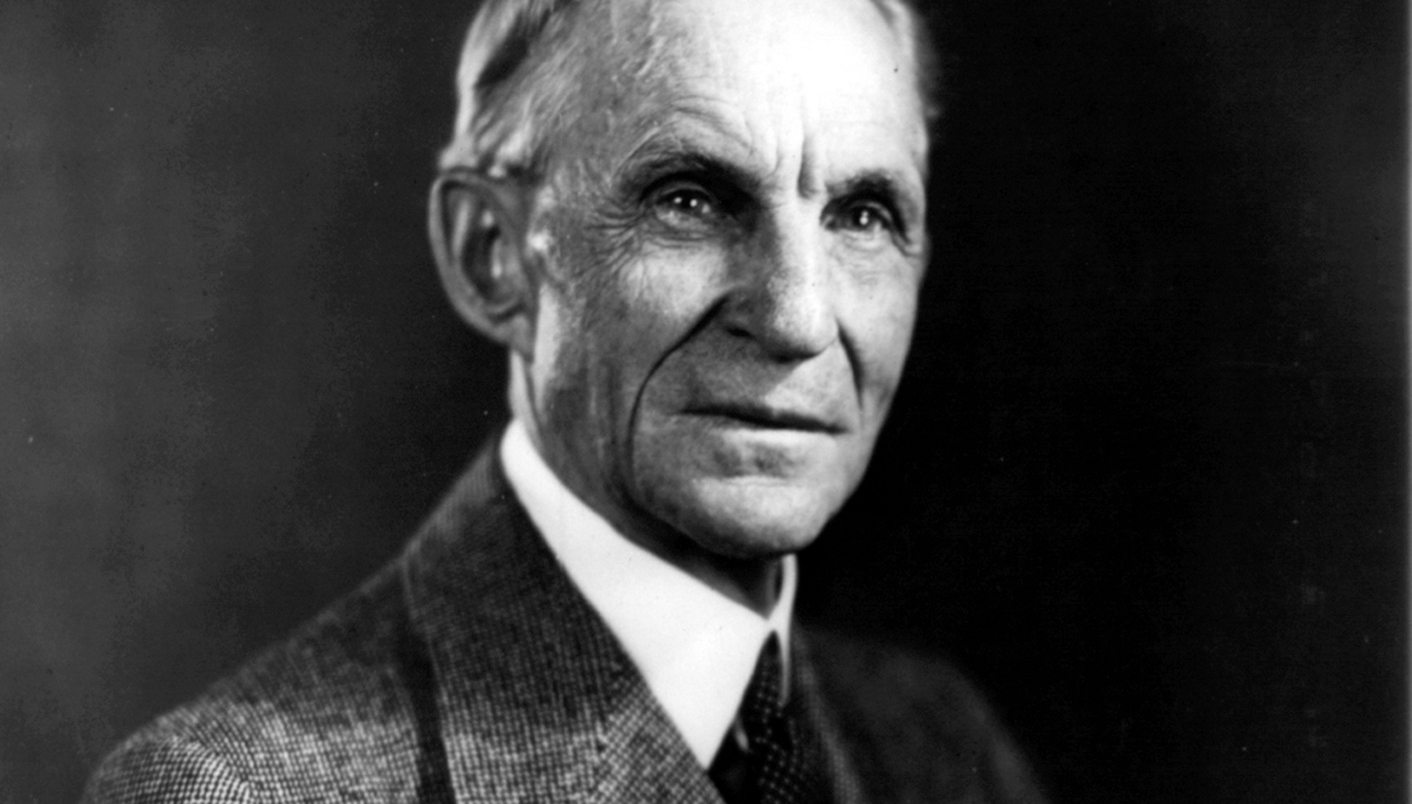

This writer grew up in a working class suburb in New Jersey in a neighbourhood primarily populated by Jewish and Italian Americans. Many of these people were members of unions active in the factories nearby. While virtually every family was happily purchasing its family car and all the other consumer goods of the 1950s, very few if any of these people would have considered a Ford product as their automobile of choice – even if they admired the luxury of a Lincoln or the spaciousness and mechanical sophistication of a Ford or Mercury and flocked to see the ultra-sleek concept cars in the local Ford dealership down the street. Memories lingered a long time in this community over Henry Ford’s encouragement of physical violence in preventing unionisation in his factories – or his embrace of Nazi Germany and his affection for some pretty ugly, hardcore anti-Semitism.

Ford was in the second generation of manufacturing kings – following the success of the first round of industrial giants like John D Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, George Westinghouse, JP Morgan and others like them. He grew up on a farm in Michigan, but showed an early aptitude for tinkering – repeatedly disassembling and reassembling a gift watch – the hallmark of an inventor in waiting. After time at Westinghouse, he became an engineer with the Edison Illuminating Company. Working there gave Ford time and money for his personal experiments with petrol engines, leading to his 1896 Quadricycle, Ford’s first functional self-propelled vehicle.

That same year he finally met the renowned inventor and head of his company, Thomas Edison. Obviously impressed, Edison encouraged Ford in his experiments. Ford eventually left Edison’s company and became an independent designer and producer of his own early automobiles – although his initial models were less than successful mechanically and commercially. A series of additional ventures followed, including a promotional tour of his Model 999, driven by race driver Barney Oldfield, a tour that brought the Ford name to national attention.

Commercial lightning struck on 1 October 1908. On that day, the Ford Motor Company rolled out its first Model T automobile. Its steering wheel placed on the left side of the vehicle (consistent with the traffic patterns in America and an innovation that led every other manufacturer in the country to follow suit). But it also had a fully enclosed engine and transmission, the engine’s four cylinders were cast as a single block of metal, and it was equipped with a semi-elliptic spring suspension.

As a result, the car was both a revolutionary advance and a commercial bonanza – especially given its $825 price tag, and despite its severely limited colour range – black or black. As sales and production increased, the price kept falling so that by the middle 1920s, a majority of Americans had gotten their first taste of motoring behind the wheel of one of Ford’s Model T.

Besides revolutionising the design and manufacture of these thoroughly standardised vehicles, and introducing their production on a moving assembly line, beginning in 1913; Ford generated a major publicity effort and established a national network of Ford dealers. These locally owned, independent dealers worked together with a spreading movement of automobile clubs – thereby promoting the idea and joy of free, independent travel in one’s own car. Ford also reached out to the farm market, selling farmers on the idea a Model T could be a commercial vehicle for them as well as personal transportation.

Now Ford didn’t exactly invent the moving assembly line – thoroughly standardised manufacturing production was already the case beginning with early 19th-century innovations like Eli Whitney’s mass-produced military muskets and Joseph Marie Jacquard’s loom for mass-produced, complex-patterned textiles. But Ford took the ideas of several of his employees and refined them into the moving assembly line as the industrial standard of the age. In this way, workers maintained their workstation as the increasingly finished vehicles rolled passed them and they carried out their assigned part of the production process.

By 1914, sales of the Model T had reached a quarter of a million – and two years later, the price had dropped to just $360 as sales sailed upwards towards half a million units. And by 1918, half of all the automobiles in America were the Model T’s. Production of this basic version kept up at Ford’s factory until 1927. In total, production eventually clocked in at 15,007,034. By 1932, Ford’s company was building a third of the entire world’s automobiles.

In corporate terms, as the company continued to grow rapidly, Henry Ford and his son Edsel carried off a series of complex, sleight of hand manoeuvres to drive out all his other investors, thereby giving the family sole ownership of the entire company. However, by the mid-1920s, sales of the Model T were falling as they had to face increasingly strong competition from more modern designs being produced by competitor companies, and they were beginning to allow buyers to purchase the cars on credit payment plans. Eventually, Ford was forced to develop a new, more modern model, the Model A. The success of the Model A, with four million units sold through 1931, led the company to adopt the new idea of annual model changes, ie planned obsolescence, even if the basic machinery was largely the same. Ford also began to back the credit payment system for sales, establishing the company’s own credit arm for this purpose.

In social engineering terms, Ford was an early leader in what has been termed “welfare capitalism” – but he coupled this with an adamant opposition to any form of unionisation. His “welfare capitalism” was designed to increase the efficiencies in the hiring – and retention – of the best workers – by offering a paternalistic involvement in and the governance of employees’ personal lives. As part of this effort, Ford decided to offer a $5/day wage, effectively doubling the wage rate of most of his employees and establishing a shorter standard workweek.

Highly skilled mechanics soon were flocking to Ford’s Detroit factory, improving the company’s productivity and decreasing its training costs. This Ford initiative helped point the way forward towards the building of a working class that could afford a growing number of the products of mass produced consumer goods of the new modern age – including Ford’s automobiles. This new wage scale, or as Ford liked to call it, “profit sharing”, also came with corporate involvement in employees’ private lives, monitoring their behaviour to be on the lookout for gambling and drinking – although the tougher aspects of that approach were eventually toned down.

Perhaps trying to have it both ways, in his 1922 memoir, Ford had written, “paternalism has no place in industry. Welfare work that consists in prying into employees' private concerns is out of date. Men need counsel and men need help – often special help; and all this ought to be rendered for decency's sake. But the broad workable plan of investment and participation will do more to solidify industry and strengthen organisation than will any social work on the outside. Without changing the principle we have changed the method of payment.”

However, this paternalistic side of Ford’s approach came hand-in-hand with violent opposition to labour unions. Ford took the view unions were heavily influenced by leaders who would inevitably end up doing more harm than good for their members (and his workers). He argued that unions wanted to restrict productivity to spread available work around to benefit the maximum number of workers – but to the detriment of their employers’ interests. Ford’s view – a line of argument that continues to animate a debate about economic policy - was that while mechanisation would inevitably eliminate individual jobs, the overall impact would be to stimulate the economy as a whole, thereby leading to new jobs in other quarters. That meant union leaders had a perverse incentive to generate an ongoing workplace crisis so they could maintain their hold over union members. Conversely, good management had a larger social responsibility to do the right thing for their workers – not because of a love for their employees but because in the long run it would maximise their profits. Smart managers thus had an obligation to fend off the depredations of socialists and reactionaries to create his “Ford-ist” utopia.

To prevent the rise of the dreaded automobile workers’ union, Ford brought in goons to beat up union organisers. In one attack, one of the victims was Walter Reuther, an organiser who eventually went on to head the United Automobile Workers (UAW) union. In the most infamous incident in 1937, Ford’s security men bloodily assailed union organisers as local police stood by without intervening.

Watch: PBS Experience Henry Ford

type="application/x-shockwave-flash">