President Cyril Ramaphosa’s announcement during last week’s State of the Nation Address that South African National Defence Force (SANDF) troops will be deployed to gang-ridden areas in the Western Cape and Gauteng represents a tacit admission that gangsterism and violent crime have exceeded the operational limits of conventional policing.

However, this intervention, while necessary in the immediate term, is far too narrow. It addresses the symptoms of entrenched criminality without dismantling the ecosystem that sustains it. Without structural reform, it risks becoming yet another episodic display of state force that unravels once the soldiers withdraw.

South Africa has followed this script before. Troops are deployed, patrols are intensified, and a temporary calm settles. But when the deployment ends, the underlying criminal networks remain intact, and violence resurfaces. Communities are left in the same position: traumatised, inadequately protected, and no closer to long-term safety. A military presence without an integrated, multiyear strategy does not resolve gangsterism; it merely suppresses it.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ED_321146.jpg)

Meanwhile, the human cost continues to mount. Children are caught in crossfire. Families bury loved ones. Entire neighbourhoods are normalised to fear. The question is not whether force is required in the short term. The question is why the government has failed to implement a sustained, intelligence-led, prosecution-driven strategy that would make such deployments unnecessary.

Witness on the ground and in halls of power

I speak as someone who has lived this reality. I come from Eldorado Park in Johannesburg, where drugs and gangsterism have torn through families for years. My own family has carried this burden. I have had to fight to save my son from addiction.

Today, as an ActionSA member of Parliament, I see the same devastation repeated across communities such as Mitchells Plain, Bonteheuwel, Lentegeur and Ravensmead. The pattern is painfully consistent: under-resourced police stations, hollowed-out social services, and families left to fend for themselves in the absence of a capable state.

Parts of the Cape Flats and Eldorado Park resemble conflict zones. The sound of gunfire punctuates childhood. Schools close early. Homes are no longer safe havens.

A five-year-old is killed while walking to the shop. A two-year-old is murdered while playing outside. A two-month-old baby is shot inside his mother’s home. So kan dit nie aangaan nie.

Four of the five police stations with the highest murder rates in South Africa are located in the City of Cape Town: Delft, Mfuleni, Nyanga and Philippi East. Between January and March 2025, 208 of South Africa’s 240 gang-related murders — nearly nine out of 10 — occurred in the Western Cape. In the same period, 273 of 308 gang-related attempted murders were recorded there. Almost half of South Africa’s drug-related crimes are concentrated in this province, largely in the Cape Flats.

Against this backdrop, the President’s SANDF deployment is plainly insufficient. It is reactive rather than strategic. It does not correct intelligence failures, rebuild investigative capacity, restore functional social services, clear the justice backlog, or address the economic vacuum that gangs exploit daily.

What is needed: A whole-of-society response

Last September, in the same month that approximately 50 people were killed on the Cape Flats, I handed the President a letter on the floor of Parliament calling for the declaration of a state of emergency. This is not a step to be taken lightly. It is a constitutional mechanism designed to unlock extraordinary tools in the face of extraordinary threats.

In that letter, I set out a detailed framework for a whole-of-society response.

First, intelligence-led operations to dismantle gang networks systematically, street by street, targeting leadership structures, financial flows and supply chains, rather than relying on patrols that merely displace violence.

Second, a substantial reinforcement of investigative capacity within SAPS: experienced detectives, forensic support, crime intelligence reform and adequate resourcing. Soldiers may stabilise an area temporarily, but only professional policing secures lasting safety.

Third, the parallel deployment of social workers, education support teams and community-based interventions to prevent gangs from recruiting the next generation in so-called pella pos (gangster hangouts). Suppression without prevention simply guarantees replacement.

Fourth, the establishment of dedicated gang and organised crime courts, similar to the fast-track courts used during the 2010 Fifa World Cup, to ensure swift prosecution and sentencing. Arrest without consequence erodes deterrence.

Finally, a deliberate strategy to confront the economic drivers of gangsterism through targeted skills development, enterprise support and clear pathways to lawful employment.

Absent this integrated approach, the cycle will repeat. Soldiers will withdraw. Criminal networks will regroup. Communities will return to the same conditions of fear.

At its core, this crisis is a test of political resolve. States of emergency in our past were instruments of repression. A modern, constitutionally bounded state of emergency must instead be an instrument of liberation that restores the rule of law and the right of communities to live without fear.

We must use every lawful constitutional tool available to secure a durable peace. Every delay carries a human cost measured in funerals, grieving families and futures cut short. DM

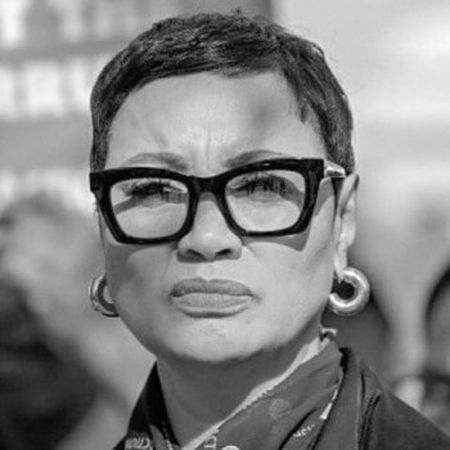

Dereleen James is a community activist from Eldorado Park and the founder of the Yellow Ribbon Foundation, an organisation dedicated to preventing substance abuse. She serves as a Member of Parliament for ActionSA and sits on the parliamentary committees for police, correctional services, and social development. She is the deputy chairperson of the multiparty Women’s Caucus in Parliament.