Soon, the minister of basic education will step up to a podium, draped in the velvet of officialdom, flanked by shiny trophies and beaming officials. A single pass rate percentage will be unveiled, a number polished to perfection. Newsrooms will run photographs of top achievers, those rare outliers who made it through the system’s furnace and are now held up as a symbol to hide the cracks in the walls.

But, as a mental health practitioner, I have worked with the children behind those walls, and I refuse to clap. My hands and heart are too heavy. To clap for the pass rate is to become complicit in a tragic masquerade. It is to admire the golden paint freshly rolled onto the hull of a ship that is already taking on water, tossing confetti onto the deck of a Titanic that has been sinking for years.

The reality on the ground

The cameras never capture the silence of my therapy or assessment room. I work with bright adolescents who are eager to be heard. They have stories inside them; stories of survival and trauma. But what always breaks me and makes me shed a tear is knowing that, despite their hopes and dreams, their future is grim because of the failures of others.

When I ask these learners, full of potential, to write down their thoughts and complete simple tasks my 5-year-old niece can do without hesitation, the air seems to leave the room. I see the physical recoil. The shame that rises in their cheeks is not the blush of shyness; it is the red heat of humiliation.

I hesitate to ask them to write because I know the secret they have been forced to keep: they cannot construct a basic sentence. They cannot wrestle the grammar into line. These are high pupils who are nearing the exit door of the system.

I recall, with a lingering sense of shock that never quite dulls, the first time I saw the numbers that explained that terror. During my internship training, I was reviewing a learner’s marks from a quintile 1 high school when a shiver ran down my spine. The average of a Grade 9 class sat below 20% for both mathematics and English.

But the real horror was not the number itself. It was what the number meant: learners who had failed badly were still ranked “above average” simply because almost everyone else was failing too. In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. In our public education system, a learner who achieves a score of 30% is considered a scholar. At first, I consoled myself by treating it as an isolated disaster, a single school in crisis.

Then I saw it again. And again. In different districts, different schools, different cohorts. The same pattern of catastrophic averages and normalised failure kept repeating. What began as one disturbing report quickly revealed itself as something far worse. The bar has not just been lowered; we have buried it underground and handed out shovels.

The shocking, uncomfortable stats

If we strip away the public relations gloss of the “pass rate” and examine the bare statistics, the underlying reality is not just fragile, it is fractured.

Start early, where the damage begins. The 2021 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study found that 81% of South African Grade 4 learners are unable to read for meaning in any of the official languages. Let that settle in your chest. Four out of five 10-year-olds are staring at a page and only seeing ink, moving their eyes across a page for tokenism.

Read more: SA leads SADC in literacy and numeracy, but faces persistent learning challenges

By the time students reach Grade 6, the picture remains bleak. Research from the University of Pretoria indicates that only 36% of Grade 6 learners can read and make inferences, lagging behind countries with fewer resources, such as Kenya (53%) and Eswatini (51%).

And yet the machine grinds on. I have met Grade 5 learners who cannot spell their own names, yet they wake up, pull on uniforms that they sometimes wash themselves in cold water they had to fetch, and walk for kilometres in the freezing winter to attend school. They sit for hours in classrooms where the lessons wash over them.

Then the reports come home, and somewhere along the line that same child is labelled as lazy. That is not laziness. That is a heartbreaking, futile bravery. Showing up for a promise that was broken before they were born.

The ghosts of the classroom

When the minister announces the pass rate, ask yourself: A percentage of whom? Because the Department of Basic Education loves counting the finishers, but it hates counting the missing.

The Zero Dropout Campaign does the maths that the department prefers to whisper. It tracks the “Throughput Rate”. If you take 100 children who started Grade 1 together, how many actually stand there in matric to write that final exam? In 2024, the answer was only 64.5%.

The rest became the ghosts of the system: pushed out by poverty, by hunger, by violence, by learning barriers that were never assessed, by overcrowded classrooms, by a curriculum that assumes fluency they never acquired, and by the slow psychological death that comes from failing publicly every year.

Celebrating an 87% pass rate while ignoring learners who never arrived at the exam room is shortsighted. It is applauding the survivors while pretending the casualties do not count.

The disastrous implications

The Department of Basic Education is failing in its mandate, which guarantees the right to basic education. “Basic education” implies adequacy and dignity. There is no dignity in “social promotion” (or condonation), the bureaucratic term for advancing a child to the next grade simply because they are too old to remain in their current grade. We are not educating them, we are merely warehousing them until they are old enough to be an unemployment statistic.

We cannot be surprised by the result. When a learner leaves school at 18 or 20 without the ability to read or do basic mathematics, where do they go? They walk straight into the arms of crime, drugs, unemployment and teenage pregnancy.

The young man selling drugs on the corner is rarely there because he was born a criminal. He is there because the economy has no use for a semi-literate school leaver, but the syndicate does. The teenage gangster is not just chasing money; he is chasing identity, status, belonging and a sense of competence that the school system never allowed him to earn in a legitimate way. We are manufacturing our own social decay.

The call to action: From denialism to rescue mission

The first step toward salvation is radical honesty. The Department of Basic Education must stop the annual ritual of self-congratulation and admit what every teacher in an overcrowded classroom already knows: the system is failing. They must publish the pass rate and the throughput rate side by side, every year, without spin. They must treat dropout not as a footnote but as a national crisis on the scale of load shedding or gender-based violence.

But honesty alone is just a confession. We need action with urgency.

Second, the Department of Basic Education must establish an emergency task force to construct solutions. Not a steering committee where bureaucrats eat away tax money with no conscience, yet pacify us with altered statistics. Staff it with independent education researchers, psychologists, classroom teachers, teachers’ unions, community leaders and Treasury-level oversight.

Third, we must pivot toward technical and vocational pathways and stop treating skilled work like a consolation prize. Our obsession with a narrow academic university track is a cruel fantasy for children who struggle with academics but might be brilliant artisans, electricians, mechanics, plumbers, solar technicians or coders. Fund workshops, partnerships with industry, paid apprenticeships, and credible certification. Provide learners with a path to competence and income.

Targeted remediation

Fourth, we must end social promotion as a default. It is a kindness that kills. Pushing learners forward while they remain illiterate is not mercy; it is delayed humiliation. The humane alternative is targeted remediation: identify problems early, intervene and allow structured repetition where necessary, with real support rather than punishment.

And here’s where moral language matters. Prophet Muhammad said: “Help your brother, whether he is an oppressor or the oppressed.” When his companions asked how to help the oppressor, he replied: “By preventing him from oppressing.” This statement, while honoured by Muslims, holds a key moral and policy principle.

The child sitting in Grade 6, unable to read, is not merely a victim of society’s cruelty. They may become the one who inflicts cruelty. Today’s discarded learner can become tomorrow’s drug runner, tomorrow’s gang recruiter or tomorrow’s tenderpreneur. Not because they were born evil, but because we trained them to believe the lawful world has no place for them.

Helping the “oppressor” also means helping the government function effectively to seal the vacuum that gives rise to societal ills. So, this January, when the cameras flash and the minister smiles, reject the illusion. Hold the Department of Basic Education accountable and demand a rescue mission.

If it fails to acknowledge these realities and implement immediate solutions, then we, as citizens, parents and community members must take active steps and stop the “oppressors”. We must be willing to mobilise, to protest, and to shut down the failure until it is fixed. There is an African proverb that warns: “The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.” We are already seeing the smoke. A child failing is not a stranger. They are our future leaders, or our future burden.

Read more: Why South Africa’s strategic reorientation of its basic education system is now irreversible

Let us be honest about something: South Africans are experts in manufacturing change when we finally get fed up. We can bring a country to a standstill. #FeesMustFall was a testament to that. More recently, in 2025, when the nation erupted over gender-based violence, we saw what happens when public outrage becomes public action. Streets filled. Institutions scrambled. Leaders suddenly found urgency. It proved that when citizens refuse to normalise cruelty, the state has to respond.

In 2026, we need that same moral electricity for education.

Not trending hashtags for a week. Not solemn speeches on results day, but real pressure that is sustained and organised at a local and national level. Because every year we accept this collapse as normal, we sign another quiet death certificate for millions of our children’s futures while celebrating the fancy tombstone that covers the buried bodies. DM

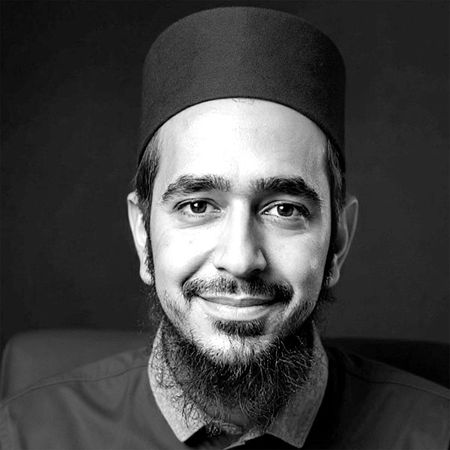

Muhammad Coovadia is an Intern Counselling Psychologist at UNIBS, University of the Free State.