Last month, the Democratic Alliance (DA) introduced a private members bill that proposes various amendments to the Prevention of Illegal Eviction and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act 19 of 1998 (commonly referred to as “the PIE Act”). Some of the proposed amendments, at face value, relate to technical, definitional aspects of the PIE Act, introducing caveats, extensions or exemptions to words such as “building or structure”, “unlawful occupier” or “reside”.

The real intent is however abundantly clear. As explained by the DA’s Shadow Minister of Human Settlements, Emma Powell — who introduced the members bill — it seeks to heighten the criminal sanctions for unlawful occupation of land, provide additional criteria for a court to consider in eviction cases to limit its application, and exempt the state from providing alternative accommodation when homelessness will result.

The proposed bill was supposed to be discussed in Parliament earlier this month but got postponed to discuss the Phala Phala debate instead. In the lead-up to Parliament’s debate on the proposed bill (whenever this may be), I provide some thoughts, remarks and criticism of the DA’s move.

Illegal occupation and urban planning

The PIE Act gives effect to section 26(3) of the Constitution which guarantees the right to adequate housing and provides that no one may be evicted from their home without an order of the court and all relevant circumstances have been considered. The PIE Act was adopted in 1998 — just four years into democracy to address rapid urbanisation with the abolition of apartheid-era pass laws.

This unplanned urbanisation led to a mushrooming of informal settlements on the periphery of urban centres. As opposed to brutal forced removals, the PIE Act seeks to provide a fair and lawful way to evict unlawful occupiers in an effort to prevent the lawlessness that dominated apartheid-era forced removals.

Regrettably, the apartheid spatial context and violent evictions have not changed, which means that section 26 is also the most litigated of all the socioeconomic rights listed in the Bill of Rights, enabling the courts to develop rich jurisprudence on the state’s obligation to provide housing when an eviction leads to homelessness (even in a private eviction).

Criminalise or decriminalise?

The most important part of section 26 of the Constitution and the PIE Act — for the purposes of the DA’s bill — is that it decriminalised the unlawful occupation of land, repealing the apartheid-era “Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act 52 of 1952” (Pisa), and made the eviction process subject to a number of requirements necessary to comply with certain demands of the Bill of Rights. The question then is why would the DA want to return to the days of apartheid when access to land was often violently policed?

According to Powell, “the purpose of the draft bill is to prevent those who, in bad faith, occupy a property or land without any legal entitlement to do so and rely on the provisions of the PIE Act to either stay on a property for as long as possible or to try and get fast-tracked in the queue for low-cost housing projects.” In the explanatory comment, Ms Powell refers to this as “orchestrated and illegal land grabs.”

All this is problematic in so many ways.

The state has systematically failed to deliver housing

Firstly, the DA’s argument is premised on the notion that the millions of people waiting for housing must wait… patiently… for their turn… while the state… slowly… builds housing.

But we are close to three million households on the mythical waiting list. Many of these households are concentrated in the estimated 2,400 informal settlements nationally and millions of backyard residents. These amendments have a direct impact on criminalising the very people on the “waiting list”.

Housing delivery has declined over 20 years

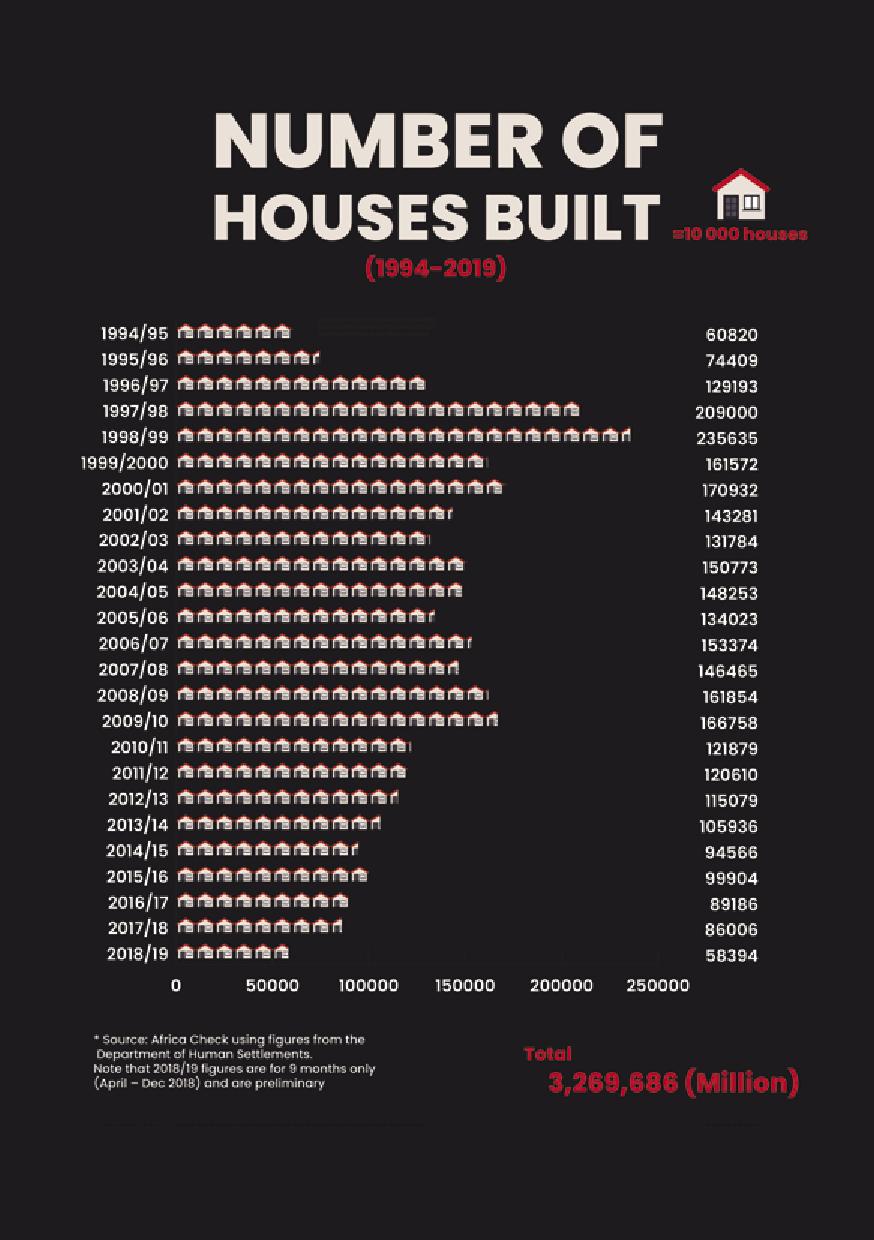

Secondly, one would think that criminalising unlawful occupation has merit if the state was actually delivering on their constitutional promises, but regrettably, the opposite has occurred with a steady decline in housing delivery over the past 20 years.

Taken from the International Labour Research and Information Group’s (ILRIG) South Africa’s Post 1994 Housing Policies and Budgets (Oct 2021)

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

The track record in Cape Town speaks for itself — a failure to keep up with delivery nor provide any other alternative.

Is resorting to crimialisation justified? Under present circumstances of severe inequality and state failure, criminalising lack of access to land and housing (poverty, unemployment) is a cheap attempt to shift blame for the state’s systemic failure to the poor themselves. Where do they expect people to go?

No positive plan to address the housing crisis

Thirdly, the DA has not presented, in its history, a single bill that addresses the housing crisis. The City of Cape Town Human Settlements strategy, lauded to be a progressive document, still lacks any implementation plan.

Moreover, the notion that the state is using its land for the public benefit is completely misleading. Even parcels of land that were allocated for affordable housing since 2011 are still sitting vacant. In fact, the City of Cape Town alone owns hundreds of parcels of land (see here for map of City-owned land), but not even a single document addresses how the land will be used to address any imminent crisis — housing, transport, public space, amenities.

At a national level, the Department of Public Works is the custodian of 29,322 registered and unregistered land parcels, and 88,300 buildings.

Definitional changes

Fourthly, the definitional changes will lead to an abuse of power. The DA wants to ensure that the PIE Act only applies to unlawful occupiers who permanently reside in a hut, shack, tent or similar structure or any other form of temporary or permanent dwelling or shelter. The idea being that it shouldn’t be forced to get a court order if someone has not resided on land long enough to establish a “place of permanent abode” and “ordinary residency.”

Of course, these words are tremendously vague and open to interpretation. Is a four-walled structure with a bed, cupboards, kitchen utensils, and clothes more or less a home after five days or five weeks, for example?

What the DA really wants is the absolute discretion to decide how, and to whom, the law applies. Does this sound familiar to you?

If the intention of the bill, according to Powell, is to prevent “bad faith unlawful occupation”, then it wouldn’t matter what the structure looks like. What matters is that law enforcement authorities (Red Ants, Anti-Land Invasion Unit and others) have the power to dispossess and place the burden on the person being dispossessed to prove, after the fact, that their home (now demolished) was a home.

It is an impossible and absurd position to put any person in. It also reverses the intention of the PIE Act which was to ensure that courts decide what a home is based on evidence before the demolition occurs. The DA’s way is to subvert the judiciary whereas the PIE Act way is to uphold it, no matter its form.

Alternative temporary accommodation

The last notable amendment is that the DA wants to shorten the length of time needed to provide emergency housing to evictees. Over the years, temporary accommodation provided for by municipalities has become de facto permanent. However, the lack of affordable housing by the state or private sector (and also job opportunities) creates a bottleneck effect where occupiers have no other options.

In sum, it all boils down to whether the DA can have its cake and eat it too. It wants to criminalise the lack of housing, in a housing crisis, without having to fulfil its local government mandate to provide housing.

MP Emma Powell, do you not see the irony? It is clear that these amendments do not provide a solution. In simple terms, if you are landless or homeless you are essentially a criminal. The state is providing very limited housing in its problematic “waiting list”. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A right to adequate housing cannot justify land theft. If the PIE Act allows it, then it is bad and stupid.

The PIE Act threatens the most fundamental right of property ownership and to enjoy the use of that property from external actors. That the right to housing is a constitutional right cuts both ways, a point Jonny Cogger ignores. The mushrooming of informal settlements following the implementation of the Act is surely not in any way a successful outcome. Cogger mocks the ‘mythical’ waiting lists and bemoans the State’s inability to deliver housing, but directs no criticism in that direction. The DA’s proposal is a (small) attempt to slow the destruction of public spaces, which are clearly vulnerable to orchestrated invasions. Cogger offers not a single point in how to deal with that threat. The economics of property destruction are straightforward. In Cape Town, it’s Table Mountain National Park is an unfenced open space. It’s green belts and walkways are open access, as are most of its parks. Road reserves are generous at certain interchanges. Agricultural activity in the form of wine and flower farming takes place within the metro. If left unchecked, these could all fall to Cogger’s shanty towns. The result is massive property devaluation in those areas, an exodus of ratepayers, the collapse of the tourism industry, and a shrunk economic pie. Any thoughtful (and honest) reflection of both the underlying problem and the potential problem would conclude that the PIE Act as it stands is lopsided, incomplete, and needs to be countered to ensure balanced outcomes.

As with all activist articles, no feasible alternatives are presented, just alot of accusations. Surely the author understands the issue when people can simply just steal property from others and there is no proper legal recourse to defend yourself. Hopefully he understands that some issues such as crime and infrastructure destruction are realities that at least in part is the fault of the homeless and land invaders in informal settlements and other forms of land theft. And currently the law seems to protect the thieves and not the people that legally and through hard work only try to provide for their family and loved ones and carve out a safe space in a country whose government has given up caring for them and focuses primarily on corruption and theft.

Empathy for the homeless is a must I completely agree with that part, but sweeping real issues under the carpet will not help. Nor will demonizing concerned citizens and parties that consistently have fought against corruption and for the good of all in South Africa.

Lack of housing has its primary roots with the ANC, with years of neglect and corruption. Blaming the DA for lack of progress is a little disingenuous. In the mean time much of that money is being used to support a huge influx of economic refugees that come because it’s not all collapsed here yet, maintaining infrastructure so that there are at least some jobs and economic opportunity here. DM, can we get a balanced article on this topic?

A nonsensical analysis. When a person decides to make their “home” on a busy City pavement, or on a railway line, there is no reason why law enforcement should not remove them forthwith. The idea that a manifestly illegal structure such as these requires requires a court order to be removed is a silly as demanding a court order in order to arrest a shop lifter caught in possession. The author signally fails to deal with the very real jumping the queue syndrome: he seeks to reward illegality with reward, and reward patience with infinite delay.

A little common sense, perhaps?

The problem with this story is that it is politically partisan, and, in fact, situated in an ideological bubble – the dream of a better future for all. A good dream, and at some stage perhaps even possible to realise – though that is of course debatable – but sadly Dr Cogger, that dream has been smashed beyond recognition by the ANC’s tragic failure as a government. The PIE Act of 1998 fulfilled certain criteria evident of it’s time, but as old apartheid laws become unacceptable, so do other laws. Times have changed, and laws must change along with them, or they become counter-productive. Has Dr Cogger ventured out into the streets of Cape Town recently, where literally thousands of people are making ‘homes’ on every available piece of open public ground? Often this is between lanes of a busy highway! This is no life, and those people have no homes, in any sense of what a home is. And no City, regardless of it’s political ideology, can afford to allow a situation like this to continue, never mind grow. It is a health, social and policing disaster that should have been nipped in the bud years ago. The accusation that the DA is resorting to apartheid tactics is a cheap shot. A solution has to be found, and your argument is not helping.

Based on the indicated housing delivery figures it is clear that the City of CT is not dealing with the issue on all fronts and (to quote from Martin Neethling’s comment) “Any thoughtful (and honest) reflection of both the underlying problem and the potential problem would conclude that the PIE Act as it stands is lopsided, incomplete, and” can only be effectively to be countered if the CoCT accepts the challenge of implementing an effective strategy for housing delivery to ensure balanced and sustainable long term outcomes. Yes, it is not only a problem of the city’s making but the city is clearly not doing its bit. By all means, look at the legislation and how it can be enhanced, but doing so without also provide substantial additional solutions will just shift the very real & major housing problem to another area of conflict and misery…

To commenters asking why no suggestions are made in the article, proposed solutions exist in abundance. Take a look at the work of the Development Action Group, for example. At the very least, the city needs to release land and provide basic services, and to do so in consultation with poor people rather than taking a paternalistic “we know what’s best for you” approach. Wasting time and money in court to win property for private developers (e.g. the Tafelberg site) should be a definite no-no.

If you’ve invested in property and the redress of spatial apartheid causes that property to lose value, the responsibility is yours for making an investment based on the cynical assumption that poor people would remain forever excluded from the area. You took a risk and it didn’t pay off – tough break. Such is investing.

For those who feel inclined to believe that the DA at least has good intentions regarding the unhoused, let’s not forget how at the start of the COVID lockdown the city herded homeless people into what was essentially a concentration camp with woefully insufficient facilities. That was the point at which I stopped giving them the benefit of the doubt.

The garbage in this article seeks to turn Cape Town into a slum city where crime and criminality is the order of the day like other metros that have been run by the ANC. Cape Town is probably the only city that you can park your car safely in this country. As a tourist destination, it provides a lot of jobs to people within the CBD unlike other cities. You can walk in Cape Town at night without fear unlike here in Johannesburg. The drivel that put talk of spatial planning mean that the cities of our country must be turned into slums with dirty and smelling streets. We must reject these clowns and their fantasy ideas that are destructive! The nonsense that we must have a nanny state must removed because we need to get people to work and there is dignity in work. When people work, the less dependency on the state for many things. These are clowns who think money grow from the trees and some investors somewhere owes South Africa some investments. The real world does not work on fantasy.

I simply do not understand the principle that its the taxpayers’ duty to provide housing (and free scholing, medical, etc) to the poor. So, I can have as many children as I wish with no consideration for the consequences as those who pay taxes will be expected to look after them. How does this make any sense?

The PIE Act is an abomination. Badly drafted and costly to implement. Layers of legal process to follow to liberate your property from a non-paying tenant or illegal occupier that can take months and many thousands of Rand even if you yourself are struggling financially. The writer’s bias and one eyed point of view diminishes his argument and reduces the problems facing the homeless to a class battle. Hardly constructive at all.