In 2001, Eskom won the Financial Times global power company of the year award for providing the world’s lowest-cost electricity.

In 2020 the rating agencies declared Eskom a major systemic risk for the South African economy and the Special Investigating Unit (SIU) informed Parliament that more than 5,000 employees were being investigated for possible criminal behaviour over a number of years.

Over the 12 years since 2009, Eskom has had 12 (acting and permanent) chief executives (CEs), six different chairs of the board, and 60 non-executive directors on the board. All the decisions made over this 12-year period about these positions were political decisions made by the ANC in government. This is a fact that cannot be denied.

While a national smear campaign builds up against André de Ruyter (supported by some senior ANC leaders), if longevity is a measure of success for the person who has the most difficult job in South Africa, then without doubt De Ruyter must be the most successful non-acting CE of Eskom since at least 2009.

What a sad state of affairs.

No company, no matter how robust, can survive the impact of changing CEs on average once per annum; nor can it be expected to survive this extreme level of politically instigated board instability.

Couple this to the fact that Eskom was simultaneously targeted by the State Capture looters because it was the biggest golden goose of them all, then what you have is the perfect storm — wanton looting plus poor governance.

Don’t forget: the investigation by the SIU and law firm Bowmans looked into R178-billion worth of suspect expenditure. No wonder the proper maintenance of the power stations was neglected.

This is why we have load shedding today. No other reason. To blame the current CE (who started his job in January 2020) for load shedding today — without any reference to the institutional turmoil, directionlessness, skills losses, looting and governance failures that occurred over the past 12 years — makes absolutely no sense. It is a form of profound managerial denialism that one would expect from the apologists for the looters, but not from anyone else.

It would be a mistake, however, to focus purely on political interference in the appointments of board members, board chairs and CEs. We have Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana to thank for his frank admission that political interference has in the past extended deep into the operations of Eskom.

He is quoted as saying: “He was allowed to do planned maintenance the other guys were not allowed to do. We don’t see the results of that planned maintenance; he’s cut us out of electricity doing planned maintenance. The indication is that there are more blackouts under him than ever, in the midst of lockdown.”

In other words, if we ask why previous CEs failed to adequately maintain ageing coal-fired power plants, the answer is that they were prevented from doing so by the politicians who instructed them to “keep the lights on” at all costs.

But there is more to it than this. We need to ask: why is the quality and effectiveness of maintenance declining — despite more and more money allocated to maintenance and more and more time allowed. This is not just a matter of badly maintained machines being irreparable — it is surely credible that this also has to do with organised crime, looting, deliberately poor maintenance and, indeed, sabotage.

If the organisers of the July insurrection could justify to themselves the televised wrecking of entire commercial infrastructures plotted via Twitter, it is easy to imagine how similarly minded people can cut bolts to topple pylons, fail to switch off critical valves, or throw a bolt into a nuclear reactor.

Since 2010, Eskom increased maintenance allocations to the Generation division — in recognition that not enough maintenance had been done since 2003 and that maintenance catch-up was required. However, despite all the managerial attention and resources since then, the generation performance continued to decline (see diagram). This could be due to constantly band-aiding a technical problem versus fixing a piece of equipment properly.

It could be due to equipment not being procured in time, or negligence or sabotage, or attempts to embarrass the current management team and recapture the company. There is evidence for all of this. To ignore all this and blame the current top Eskom leadership defies all logic and negates the evidence.

But the problem is much deeper than leadership failure, political interference or sabotage.

Something much more profound is going on, with deep roots in the twilight years of the apartheid era. According to research by Erica Johnson, former Eskom executive and currently a doctoral research student at the Centre for Sustainability Transitions, Stellenbosch University, the roots of the problem lie in the adoption of the recommendations of the De Villiers Commission of Inquiry (1983).

The De Villiers Commission was established to examine Eskom and electricity pricing throughout South Africa. Its far-reaching recommendations ushered in a new techno-political regime during the period 1987 and 2001, during which Eskom was incorporated as a company and the National Energy Regulator (NER) was established.

Uninterrupted by the transition to democracy in 1994, over this period Eskom went from being self-regulating (in its parastatal phase) to agreeing to politically directed (via the board and CE appointments) price compacts to reduce the real price of electricity between 1985 and 2000 by 20%. This suited the post-1994 government’s focus on its “electricity for all” campaign and its desire to control Eskom’s strategic directionality.

Herein lies the origins of Eskom’s fate as an instrument of political control which, in turn, paved the way for Eskom as the prime target of State Capture.

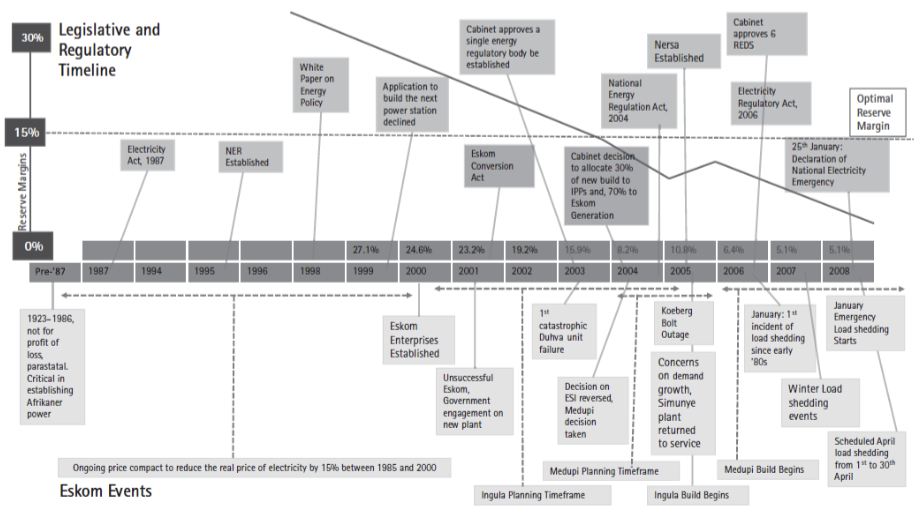

As reflected in this diagram, two decades of liberalisation (promoted by Eskom’s management) and decreasing autonomy (due to political interference) led to the first coal crisis of 2008 and the start of load shedding.

Tumultuous decade up to the second coal power system emergency — declining grey line is the reserve margin over time. (Source: Erica Johnson)

Between 1998 when the White Paper on Energy Policy was published and 2003, the reserve margin (declining grey line in the diagram) dropped from more than 30% to below 15%, and continued its decline to near zero by 2008 when the first load shedding began.

During this period, Eskom’s requests to build new power stations were repeatedly rebuffed by a government that believed it was possible to reconcile low electricity prices and private sector investment in new power plants. No one seemed to have realised that you can have one or the other, but not both.

In 2008, President Thabo Mbeki apologised to the nation for ignoring Eskom’s requests. But by then it was too late.

The structural decline had set in. Successive CEs — Thulani Gcabashe, Jacob Maroga and Brian Dames — all pledged to fix the problem and pleaded with the nation to understand how serious the crisis was.

The decline could have been reversed to some extent if managers were allowed to properly maintain the power plants and if the extent of the power system imbalance articulated in technical terms by the engineers was properly understood by the politicians. And above all, political support to enable Eskom to re-establish energy security in the country.

As a result, Eskom lost key skill sets as the best people resigned. By the time Eskom was “allowed” to build Medupi and Kusile in 2005 (the third and fourth biggest coal-fired power stations in the world), it had lost the capacity it needed to do what was, by any global standards, an incredibly complex job.

Ultimately, what was supposed to have cost R163.2-billion with a completion date of 2015, has ballooned to an eye-watering R450-billion (Kusile is still not complete). Herein lies the origins of the Eskom debt crisis.

Long before De Ruyter arrived on the scene, former Eskom board chair Jabu Mabuza told Parliament in September 2019 that Eskom’s revenues were such that it could only support debt of R200-billion. However, at the end of March 2019, Eskom had debt of R440.6-billion.

During the year to the end of March 2019, Eskom paid interest of R30.2-billion on its debt, which was equivalent to 16.8% of its revenues.

An analysis of Eskom’s income statement shows that its costs were about 115.6% of revenues in 2019. Therefore, the gap between revenues and costs is almost the same as the interest payments.

So, Eskom kept borrowing to pay off its debt. With debt of R200-billion (instead of R440.6-billion) during the year to March 2019, Eskom would have slashed its interest payments by R16.5-billion (or 9.2%) of revenues to R13.7-billion, assuming an average interest cost of 6.85% and approval by Nersa of a more cost-reflective tariff. None of this, of course, materialised.

The result is that Eskom’s debt ballooned to R480-billion by the middle of 2020, with no strategy in place to resolve the problem. Just over R200-billion of this debt matures over the three years through to 2024.

De Ruyter is an industrial man through and through. He started his career selling coal and before Eskom, he was a Sasol senior executive. This is no greenie, by any stretch of the imagination. And yet, halfway through 2020 he started to realise that Eskom faces a triple challenge: (a) the power stations are so dilapidated no amount of “repairs and maintenance” will return them to their full capacity; (b) as his predecessor (Phakamani Hadebe) said repeatedly before resigning in late 2019, no one was going to provide Eskom with funding for a new coal-fired power station — and even if they did, it would take too long to build to stop load shedding (ie 10 years); and (c) unless 25GW of additional capacity were built by 2025, South Africa would face permanent load shedding.

The only way to achieve the latter, he realised, is with renewable energy — it was cheaper than coal; each plant could be built within two to three years and lots of cheap capital was available for investing in renewables. Hence his now famous phrase: “Let’s turn coal shovels into turbine blades.”

In his presentation to the Presidential Climate Commission in July 2021, De Ruyter demonstrated that nearly half the current generation capacity must be closed down by 2035 for purely technical reasons, which means 5-6GW of renewables must be built every year from now onwards to keep the lights on.

South Africa’s three expert energy modelling teams — at CSIR, UCT and Eskom — support his conclusions.

In his Van der Bijl lecture on 17 August 2021, De Ruyter drew out the economic implications of this when he said: “The economy was built on cheap coal, cheap energy and cheap labour to power a primary commodity economy. Structural underpinnings haven’t changed enough, and are not suited to global transition.” (Noteworthy is that the written text of the speech does not refer to cheap labour.)

Eskom has made it clear that this energy transition must be just and well-managed over 20-30 years. Not a single person or organisation supportive of the energy transition has ever suggested “turning off the lights to breathe clean air”, as suggested by the Department of Minerals and Energy and its Minister Gwede Mantashe. No one.

And for most who advocate renewables, it is not actually about carbon emissions (ie “clean air”) — it is about the cheapest available electricity phased in gradually over time to achieve what Minister Godongwana insisted in his Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement is the real goal — energy security for economic recovery (not saving Eskom).

This happens to also save around 1Gt of carbon by 2050 if done well, for which concessional financing is available. But that is just a bonus worth grabbing.

The explanation for the smear campaign being waged against De Ruyter should now be clear. He has taken on the State Capture forces embedded within Eskom, and he has taken on the vested interests in the coal-based energy industry. In some cases, these overlap, and the tentacles of both run deep into the political establishment.

They now have a common enemy.

Unfortunately, they are joined by some unions who have ignored the evidence that coal jobs are already disappearing (unrelated to renewables) and that the just transition (first articulated by Numsa years ago) has the potential to generate far more jobs than currently exist in the coal sector, especially if upstream industrialisation is taken into account.

In short, from a long history perspective, Eskom’s troubles have deep roots in the pre-democratic era. Liberalisation was misconceived, creating the delusion (avoided, by the way, elsewhere in the world where liberalisation took root), namely that regulated low prices and private sector investment can be reconciled.

By delaying the big decisions, the government handicapped Eskom and it never recovered.

By the time the State Capture looters targeted this stumbling behemoth, it was too weak and too captured to resist what followed. Enter Molefe and Koko as CEs who were politically instructed to stop load shedding by overloading the unmaintained machines, and you have the imbroglio that De Ruyter inherited.

To assume all would be okay with the right man in place is exceptionally naïve under the circumstances. It ignores historical realities, structural dynamics, financial facts and serious political misjudgements. Former president Mbeki was gracious enough to take responsibility by apologising to the nation. But that was in 2008.

But there is one more narrative that has entered the mix — and this is, of course, the classic South African race card. Thinly disguised by some, but made explicit by others, there is a continuous flow of suggestions that somehow De Ruyter is tolerated despite his obvious failure to stop load shedding because he is seen by the powers that be as the “white saviour” — read: untouchable.

“If he was black, he would be fired,” we are told.

In a country with mounting racial tensions and an economy where more than 90% of all assets are owned by less than 10% of the population (most of whom are white), it is unsurprising that non-racialism is on the decline. But to use the race card against a man who has chosen to risk all for the sake of a truth that the future of our nation depends on is deeply disturbing, and frustrating.

It is a cheap trick to mask the real agendas of those who want to resist the dismantling of State Capture networks and those who want to resist the inevitable transition to a net zero carbon economy. Who do they want to replace him?

It’s time we realised that Eskom does not need a 13th CE in 13 years.

What the 12th CE needs is full-scale political support from those who appointed him; full support from the law enforcement agencies to bring the looters to book; a funding solution that resolves the liquidity and debt problems; an internal team that believes in the mission, and full support from the South African nation as it battles through load shedding until the day arrives when load shedding has ended — that will be the day when most of the old power stations are closed and the landscape is well-populated with windmills and solar panels.

Let’s play this game, and not the man. DM

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8835″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Fully agree. And yet, we should never put all our faith into one person. How strong is the internal team around this CE, and their joint belief in the vision of and end to load-shedding and their mission to accomplish it?!

An excellent analysis. Maybe it’s time for parliament to pass a law that puts Eskom beyond the reach of political interference. After all, the consistent supply of affordable electricity to all should be placed in the hands of skilled experts and not politicians!

Very well said. Overseas most governments have technocrats as ministers. Mainly in technical related departments. Here we have “Comrades”. That says all!!

Its very frustrating to hear people attacking de Ruiter on media platforms with clearly race based claims. One young woman interviewed on SAfm was so hysterical that she couldn’t jump her cognitive dissonance of being saved by a white. It is frustrating, but also sad about our country’s youth.

On another point, it seems that the entire system of electricity grid economy is locked in the neoliberal bubble. If the domestic sector comprises of less than 20 % of electricity use, firstly, people should be encouraged to become independent and feed back into the grid, and second – industry must be incentivised to do the same. At present the ideas of taxing off-grid households for “availability” and all the other tax base prop-up ideas bandied about by nersa is short sighted and crippling.

Thank you for this very helpful and thorough analysis of the crisis. It is unclear if it will be possible for the major root out of corruption will be able to succeed. Government does not seem likely to provide the required backup. Pressure by citizens and civil society it seems will be critical. Another part of the crisis is the active suppression of the development of renewable energy sources for years, and even now delays by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy in opening up the grid to renewable energy means that the current crisis is worse than it otherwise would have been, and will take unnecessarily longer to alleviate.

Accurate and incisive (fact based) analysis, thanks Mark! In essence, allowing government officials and (worse) members of the formal (government) and ‘informal’ (ANC) political structures to interfere in the operations of SOE’s has simply allowed the unscrupulous among them to loot the SOE’s. The rot started with government’s fantasy that it could run the electricity system as a government department (in the early 2000’s), it really set in with the ANC/Chancellor House corruption in the mid-late 2000’s, and with that demonstrating there would be no accountability for being found out looting, with senior ANC officials deeply implicated, it was Open Gates. Everyone with a mind to could join in. De Ruyter, and the drying up of the cash pool, is closing those gates. But we are left with either no effective energy policy (my view) or a ridiculous attempt to re-open the rent-seeking gates – Minister Mantashe’s ‘vision’. Pravin is nowhere to be seen because his vision of using the SOE’s to establish a developmental state died because they are so bankrupt the government can barely afford to keep them operational, never mind using them to achieve social objectives. The focus now HAS to be on supplying enough electricity for basic services and economic production and the ONLY techno-economic and financially feasible option is rapid acceleration of REI4P plus extending RE rollout to public and community (municipality) and commercial own-supply RE onto the grid as fast as possible.

A big chunk of the financial problem at Eskom is far too many and vastly overpaid staff

By now I’d expect the CEO to not only identify that problem but also have taken steps for right-sizing the headcount. So that issue is his.

But the state and inadequacy of the fleet is not his fault.

As recalled-at an early stage( and just after he was appointed) de Ruiter was instructed by government that there was to be no reduction in Eskom staff numbers(not withstanding which he has always maintained there has been no political interference to his task).

I remember thinking he should have turned his back and walked away that instant.

He is faced with an impossible task and the government has no inkling what goes on in a power utility and are not supporting him as they should.

Those who know the operation and in particular those engineers who were forced out and replaced by cadres can only shake their heads in cynical disbelief.

If government were serious they would call those guys back. Not going to happen-too much loss of face.

Lucid, fair and fact based, as opposed to the ANC asking everybody “what is going on with Eskom?” As if this way the party can absolve itself of the years of mismanagement, non servicing, and sheer thievery that characterized its involvement with the power utility. It is too late to distance itself – the truth a hasbeen out for quite some time!

Finally, a rational set of arguments ‘illuminating’ our current energy crisis. Thank you Mark Swilling.