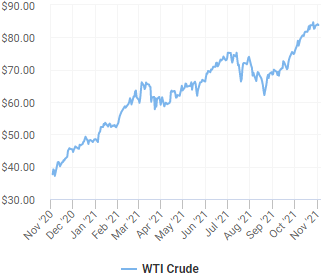

As the chart below shows, and cash-squeezed South African motorists know all too well, the oil price has more than doubled over the past 12 months, recently reaching highs not witnessed for several years.

While this is ostensibly good news for producers and commensurately bad news for consumers, the latest surge in prices presents challenges to both sides of the market, regarding their hedging strategies going forward.

The recently released 2021 Global Risk Management Survey by the international insurance group Aon ranks commodity price risk as the fourth most pressing concern for over 2,300 polled key risk decision-makers in 60 countries around the world, the highest since it was added to the list in 2009.

Oil hedging has somewhat of a chequered history, and attempts by corporations to reduce their exposure to the wild gyrations characteristic of this market is generally regarded as a case study of what not to do, rather than one of sound risk management. Some commentators have even proposed a trading strategy, according to which one should buy oil when producers lock in selling prices and sell when large oil-consuming entities lock in buying prices!

Airlines, in particular, have been extremely adept at screwing up when it comes to making strategic decisions to limit their exposure to the price of jet fuel, which is obviously highly correlated to the price of crude. The well-publicised and substantial oil hedging losses of African carriers such as Air Mauritius, South African Airways and Kenya Airways are mirrored by the losses experienced by their international peers; for example, Delta Airlines admitted to $4-billion of losses on oil hedges in the several years up to 2016.

Producers too seem to have a knack for getting their knickers in a twist when it comes to deciding whether or not to lock in prices for future production. A report in July this year, by the consultancy firm IHS Markit, showed that almost a third of the 11 million barrels a day of US production was being sold at average hedged prices of just $55 a barrel, at a time when the market price was at a lofty $75. This equates to an opportunity loss of close to $30-billion for 2021 for these producers, based on the current price of $84. Many of these hedges were concluded during the pandemic-fuelled oil price crash of 2020, which at one point saw oil prices trading at a mind-boggling price of negative $37.

Closer to home, the South African synthetic fuel producer, Sasol, has recently announced a restructuring of its 2022 hedging programme, which allows it to secure a minimum (“floor”) price of $60.09 per barrel, rather than the previously agreed $43.11 per barrel. Nevertheless, the best (“cap”) price it can secure under these new arrangements is $71.97 per barrel, which is significantly worse than the prevailing market price at present.

What is the problem? Well, firstly, the volatility of any underlying price exposure is a key factor, and oil prices are among the highest, which, at best, makes forecasting a very difficult science and, at worst, a dangerous basis for formulating risk management decisions. Nevertheless, as with other areas of financial risk management, many corporations appear to blindly follow such forecasts, despite a wealth of evidence that “they are about as reliable as guessing”.

A second problem encountered by hedgers of oil exposures, again linked to the characteristic volatility of the price, is the cost of option hedges. Options are hedging instruments that guarantee a worst-case price for an exposure, but avoid the regret of locking in prices using simpler derivative tools such as futures/forward contracts and swaps; put simply, they are analogous to purchasing insurance.

However, option hedges require the payment of an upfront fee, known as the “premium”, which is largely a function of the anticipated volatility of the underlying commodity over the life of the option – the higher the anticipated volatility, the higher the premium cost.

Further, the tendency of many hedgers to only investigate hedging strategies when the underlying commodity price is moving strongly against them, and it is therefore volatile and likely to remain volatile for some time, exacerbates this problem.

As an example, the premium cost at present for an oil producer to purchase an option expiring in April 2022, to sell WTI crude oil at $80 per barrel, is $8.21 per barrel. While this allows the opportunity to benefit from a higher oil price, which is not possible with simpler hedges, it is still a considerable expense, and one that will often be criticised with the benefit of hindsight. For example, although shrouded in much secrecy, reliable reports suggest that the Mexican government has previously spent as much as $1.5-billion in one year for option hedges of its annual oil production.

A third problem lies in the fact that the prices at which future oil sales/purchases can be locked in via the use of derivative instruments, behave in ways which are not typical of most other markets. For example, at times of high prices in the “spot” oil market (the market for immediate sale/purchase of the commodity), the price at which future prices can be secured is often lower, known as a “backwardation”.

This can be seen by the difference between the current price of the United States crude benchmark, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), which is trading at $84 in the spot market, but at a 12-month derivative price close to $73. This differential can quickly reverse at times of low spot oil prices, known as a “contango”, and was an important factor in the $1.3-billion losses reported by the German firm Metallgesellschaft in 1993, as a result of a flawed oil hedging strategy.

Another complication for corporations dealing with oil exposures, in common with commodities in general, is the fact that the price is quoted in US dollars, which introduces a foreign exchange component into the price risk and further complicates decision-making, at least for non-US entities. Equally, the risk of a sharp decline in demand encountered by producers as well as consumers, such as airlines or locked-down manufacturers, adds a further level of uncertainty when agreeing prices for future anticipated sales and purchases.

In fairness, a lot of the reported “hedging losses” represent more of an opportunity cost than a real loss, and everyone is always right with the value of hindsight. However, the failure of many entities to formulate a strategic risk management strategy, and to simply react when the “fit has already hit the shan”, does, however, open the door to many of the “expert critics”.

Some oil market participants prefer to remain unhedged, rather than attempt this difficult exercise, with many arguing that oil price fluctuations even out in the long run, in line with the normal business cycle. Further, some producers argue that investors in their shares desire exposure to the oil price and would certainly not welcome the news that selling prices have been fixed for a considerable time in the future, especially if they believe that prices are likely to rise.

More cynically, some argue, like Scott Kirby of American Airlines, that “hedging is simply a rigged game that enriches Wall Street”, and it is beyond doubt that providers of hedging solutions such as investment banks derive substantial profits from their activities. Add in the often onerous requirements of hedge accounting rules and compulsory collateral agreements for the use of derivative hedging instruments, and it is clear why doing nothing is sometimes the preferred solution.

In the words of Raoul LeBlanc at HIS Markit: “If you get hedging right, people don’t give you credit for it. If you get it wrong, you get hammered.”

Essentially, it often feels like you’re damned if you do, and damned if you don’t. BM/DM

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8851″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.