The digital divide has been magnified during the lockdown periods precipitated by Covid-19. Online teaching and learning have become vital elements of schooling, yet this has not been the reality for nearly 80% of children in South African schools.

Multiple voices across South Africa have declared that limited access to the digital highway is an insurmountable challenge in the short term. Those with the power to change this polarised reality quickly seem to be frozen in the Covid-19 headlights. It is a sad reality that the majority of our children continue to be further excluded on the basis of these assumptions.

Is it possible to reimagine a world in which every school-going child in South Africa has access to the internet? Of course it is – and with almost immediate effect, if we unlearn our assumptions and act quickly to empower our children to take control of their own individual learning journeys.

In Daily Maverick of 6 September 2021, Pauline Hanekom outlines an encouraging response to the digital divide in an intervention in the Breede River Valley near Worcester in the Western Cape, where farmworker children are being taught digital skills in farm schools (“Onward and appward: How digital skills help to change the lives and futures of children in Western Cape farm schools”).

What we know is that even if schools have access to the internet, this doesn’t guarantee access to all students in each of those schools. It would shock most people to realise that even in relatively well-resourced schools, access to internet-connected computers is, on average, limited to a few minutes rather than hours per week. I have no doubt that the Breede River Valley project is addressing this to increase contact time.

Questions: Do the children take the tablets home or can they only access these in the school context? What is the average contact time between child and device on a daily basis? Do the tablets enable students to use these online at home?

Clearly school computer rooms are not going to solve the problem of the digital divide. In addition, it remains an unchallenged tragedy that most of these computer rooms are locked for at least 70% of school time and 100% of the time during school holidays.

The August 2019 National Education Infrastructure Management System report suggested that only 20% of SA schools are connected for learning. This analysis leads us to a hand-wringing conclusion that not much can be done to change the reality that most children in lockdown have no educational support from their schools. The reality of this view is that teachers and schools are seen as the necessary gatekeepers to our children’s access to the World Wide Web. This never applies to privileged children.

Asking the wrong question

“How many of South Africa’s public schools are connected to the internet?” This is the wrong question. The right question is, “How do we ensure there is a phone in the hand of every school-going child?” Our children know what to do with a phone with sufficient data, and they all have a highly skilled TikTok peer support group willing to teach and guide.

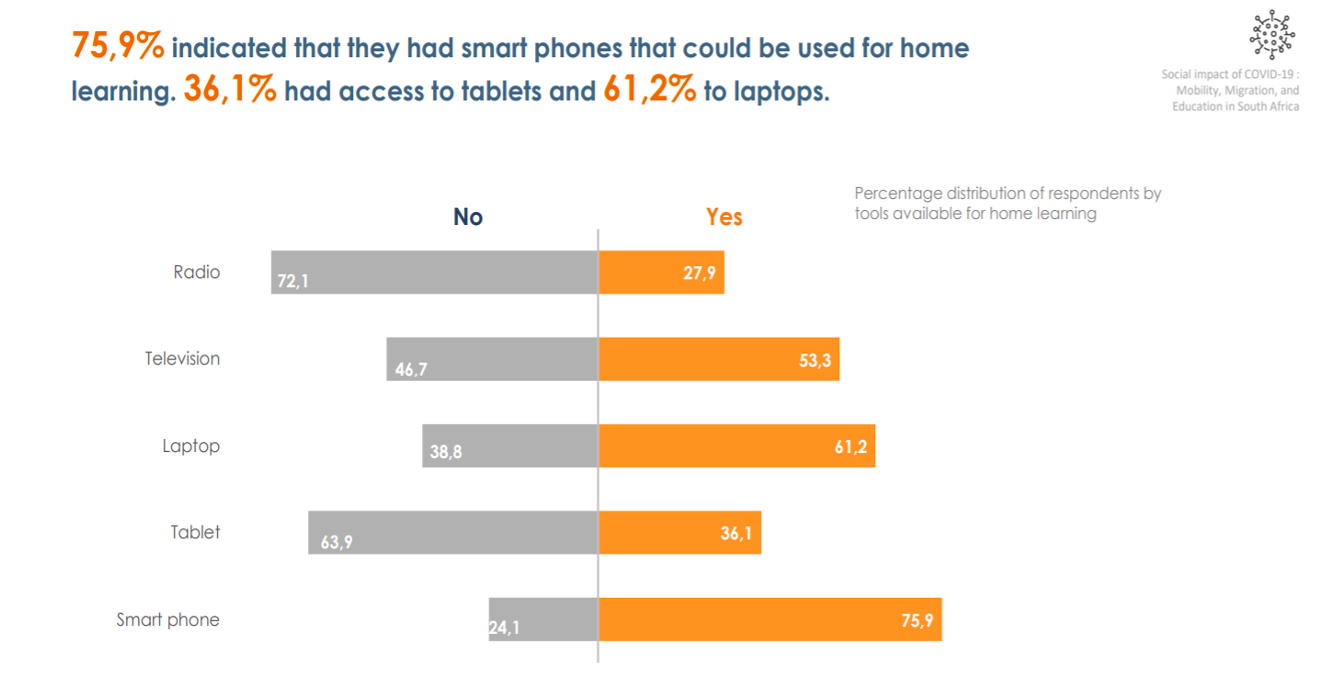

There were over 100 million cellphone connections in South Africa registered in January 2020 – equivalent to 176% of the total population. There are about 13 million children at schools in South Africa. A good, usable, Android cellular device can be bought for R1,000. Access to zero-rated educational materials is easy and beautifully endless on such a device. Some data contracts allow “bottomless” access with some peak-hour timing constraints for R99 per month – this could be negotiated by government with data providers to at least half this price.

If we choose to put phones into the hands of all children with enough data to ensure ongoing access to the internet, it would cost no more than R1,600 per child for the first year (being R1,000 for the device itself and R600 for data).

Subsequent annual costs for those students who have previously received a device is only R600. Clearly the Department of Basic Education (DBE) would not need to provide phones to all students – probably fewer than 30% of children (as the other 70% already have devices to hand). This 30% will account for four million students in year one. This would use, at most, 2.6% of the national annual budget of over R260-billion (i.e. R6.4-billion), which amount would easily be accounted for due to a drop in the DBE’s annual spend on textbooks and provision of computers to schools, as the majority of information contained in the textbooks is accessible online using the device and data.

This solution is completely within our grasp.

At the LEAP Science and Maths Schools, working in township communities of South Africa, this reality is being tested with remarkable response from children working with phones only – staying connected in support groups, receiving work instructions and attending virtual lessons on Google Classroom and WhatsApp, and completing assessments online.

Connected children remain self-liberating as they control their own access to teaching and learning moments, and help their friends to do so too. Teachers are able to monitor students’ online learning activity via back-end processes, including a review of how long a student has been studying online on any given day, and how often such online learning is being accessed by the student.

All children must have access to information, online lessons, assessment tools, enrichment material, global information and social media. This should not be the entitled domain of the wealthy – it can be every child’s right if – instead of imagining the schools as the place where digital learning happens – we unlock the capacity of each child to have access to the internet in their hands whenever required.

One child, one cellular device. All teachers digitally preparing and caring. This is what will change the way. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider