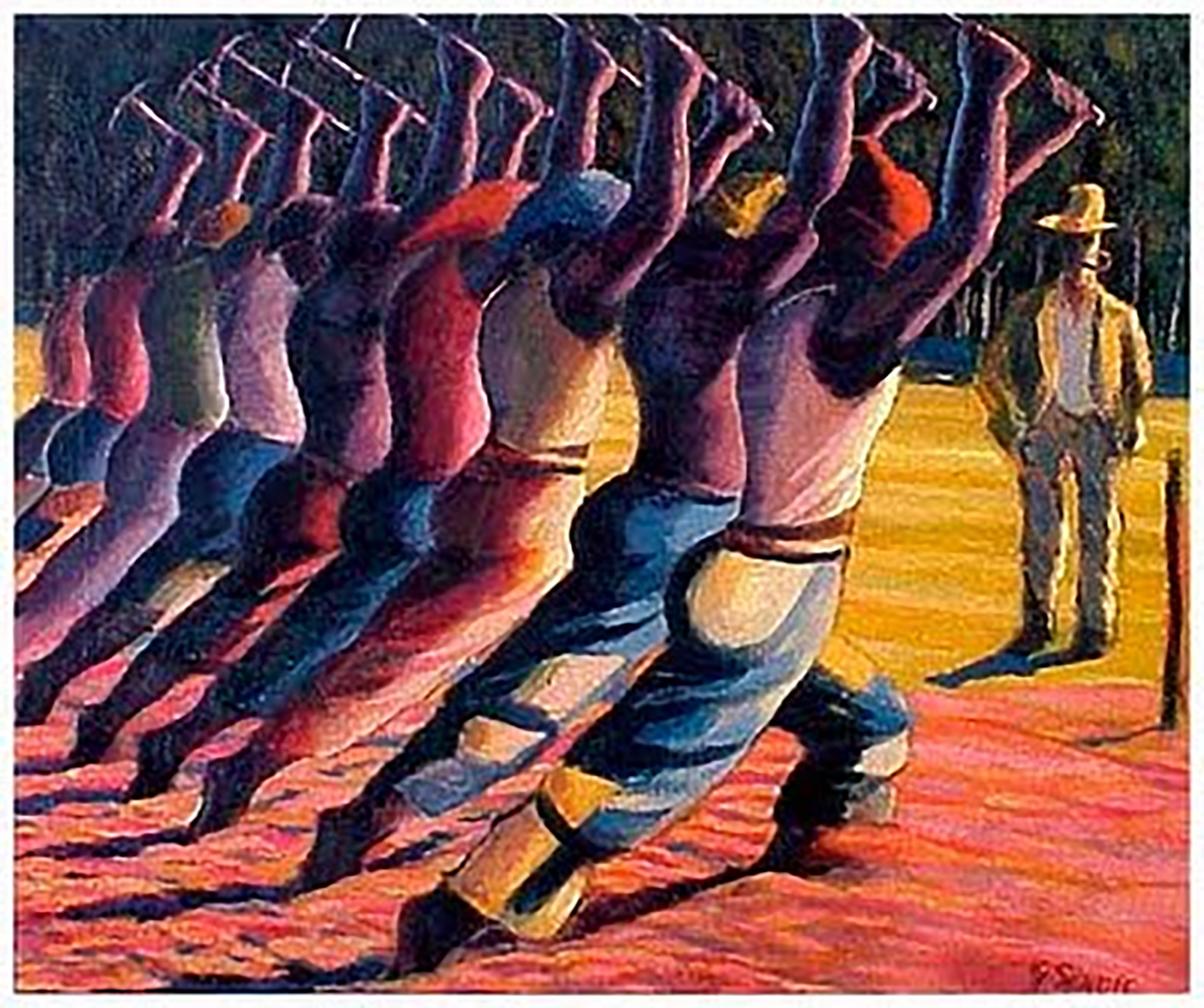

Seventy years passed between when Gerard Sekoto (1913-1993) created probably the most powerful, rhythmic and meaningful painting by a South African artist, his never-forgettable Song of the Pick (1947), and when Luthando Dyasop evoked his own experiences as a soldier in Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) in Angola, in four paintings shown two weeks ago in Daily Maverick in my article, “Out of Quatro: The ANC’s refusal to listen” (14 July).

Dyasop’s moving and often lyrical autobiography, published in paperback by Kwela Books, comes out on sale this week. Alas, in these straitened times of Covid-19, lockdown and looting of the economy both by the political elite and the dispossessed, the publisher was not able to reproduce in colour Dyasop’s four paintings of his experience in Quatro prison and at Viana camp outside Luanda, during the Cold War in the 1980s.

That will have to wait for another time.

But it is worth considering Dyasop’s paintings – in particular his painting of the attack in Angola on 12 February 1984 by Fapla, the military arm of the ruling MPLA party, on a pro-democracy movement among MK soldiers at Viana camp – in the light of Sekoto’s evocation of the drama of labour in South Africa under the apartheid system of the 20th century.

Nine men in a row – nine black men – arms raised with a pick in both hands, right leg strained behind them, are one second from striking the earth in a massive, normal, everyday, all-day, collective CRASH of steel. Their power of anonymous, faceless energy rises in the painting above the head of a solitary, white, motionless, pipe-smoking supervisor of their labour, who stands and looks. Action and inaction. A contradictory juxtaposition of power and powerlessness, of the present and the future.

There is no limit to what one senses from Sekoto’s classic painting.

The Javett Art Centre at the University of Pretoria (Javett-UP) has a very helpful appreciation of the painting on its website.

It notes how Song of the Pick is “an example of Sekoto’s early mix of the REALISTIC or FIGURATIVE mode and the more EMOTIVE or EXPRESSIONISTIC. The scene depicted cuts to the heart of colonial and apartheid control of South African society. The rhythmic, symmetrical and powerful line of the black work gang is set against the lone white “BAAS” in his khaki suit.

“Sekoto’s mastery of line and colour is evident in the implied movement of the workers – which emphasises their collective power – and in the bright colours of their headgear and pants against the vibrantly coloured earth they are about to strike. But the work does not simply reflect an ordinary social reality of labour and inequality. One can read it as a political allegory, too. The white foreman, whose suit blends with the drab earth on which he stands, is a noticeably less powerful physical presence in the picture plane, almost edged out entirely by the work gang, which looms over him.”

When we look at Luthando Dyasop’s photograph of his own painting, we sense an historical trauma of South African black society which has lasted to this day: a trauma of unaccountability, of being politically powerless.

In Sekoto’s painting from 1947, the white supervisor is unarmed – because he didn’t need to be. The police could be called if there was any threat to him. The collective power of the black labourers, demonstrated by the pick, was a political, social and economic powerlessness.

By 1984, however, when black society had armed itself against the tyranny of unaccountable minority white authority through MK and other armed resistance groupings following the massacre at Sharpeville in 1960, Dyasop’s painting shows a continuing and related powerlessness.

On a wall, the MK soldiers from the June 16 and Moncada detachments who had gathered at Viana camp have posted a banner stating “NO TO BLOODSHED. WE NEED ONLY CONFERENCE”.

Yet instead of a conference which the MK High Command had promised them, it called in armoured personnel carriers and troops of the Fapla presidential guard who are shooting at fleeing MK soldiers, and have shot dead one of their colleagues, Babsey Mlangeni, who is falling from the top of the wall (on the left).

As was reported in the collective memoir, “A miscarriage of democracy: the ANC security department in the 1984 mutiny in Umkhonto weSizwe”, which I was able to secure in April 1990 from MK refugees then living in Nairobi, and published in a banned exile journal, Searchlight South Africa the following July, “one MK combatant, Babsey Mlangeni (travelling name), and one Fapla soldier were already dead and an Angolan APC was on the retreat engulfed in flame.” (p 47)

Dyasop narrates in detail this historic crushing by armed forces of the Angolan military of the pro-democracy movement among MK troops in his autobiography, Out of Quatro. He was the MK soldier who had fired in self-defence with a bazooka at the advancing APC, also killing one of the Fapla attackers, leading later to a heavy punishment for himself by the ANC security department, Mbokodo. It is a killing for which he expresses a genuine sorrow at the end of the book, in his Coda.

He recalls how “we saw the APC driver turning the barrel of the APC in our direction. Instead of answering our question as to why they were there, and seeing that we did not intend to surrender, the commander reached for a grenade, pulled the pin and was about to throw it at us when I pulled the trigger of my bazooka. I knew what fatalities would ensue if the grenade landed in our trench.

“The sound of the rocket leaving the bazooka was so loud it disturbed him, and the grenade fell only metres from us. The others in the trench also opened fire, but only to scare the Angolans who were now running towards the camp. I had used all my rockets when I realised that the APC was in flames. With the Angolans running towards the camp, we had the chance to run further away towards the nearby bush. When the Angolans turned and saw us running, they opened fire. We were fortunate that all those bullets whizzed past our half-bent bodies as we scrambled for safe cover, and no one was hurt.” (p 125)

It is totally exceptional for a critical moment in South African history to be reflected so vividly in word and image, by one of its participants – even more than 30 years after the event.

Dyasop’s painting, like Sekoto’s Song of the Pick, is a physically powerful drama of emotive and expressive realism.

Read the book. And, hopefully, one day, see this painting at first hand, together with its accompanying paintings from that wartime experience, in an exhibition in an art gallery.

Emotive, expressive, imaginative realism… this is how South Africa’s art is made. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.