When thinking about education, and particularly education policy in South Africa, the focus is predominantly on assessing results in three spheres, namely primary, secondary or high school, and tertiary education such as university or college.

Currently, South Africa’s basic education system is delivering some of the worst educational outcomes in the world. For example, in 2016 South Africa ranked last out of 50 countries in the Progress in International Reading Literacy study. The study will be conducted again in 2021 and will cover 60 countries, so it will be interesting to see how well South Africa performs.

In 2016 it showed that most South African pupils in grades 4 and 5 could not read at the level required of them. During 2016 the World Economic Forum released a report on the quality of South Africa’s mathematics and science education, with the country placing 137 out of 139 participating countries. South Africa has repeatedly scored near the bottom of this ranking.

Extensive research and analysis have been done on the state of South Africa’s education and the problems that plague it. In February of this year, Amnesty International published a report, “Broken and Unequal: The State of Education in South Africa”, which painted a bleak picture of state education in the country. Amnesty International indicated that 75% of children aged nine could not read for meaning. In Limpopo, this number was 91%, while in the Eastern Cape it was 85%. On average, out of 100 learners who start school, Amnesty International reckons 50-60 make it to matric, of which 40-50 will pass and only 14 are likely to carry on to university.

The Amnesty International research highlighted stark inequalities in the system. For example, students in the top 200 schools in the country achieved more distinctions in mathematics than the next 6,600 schools combined. Worse still, approximately 4,358 schools have illegal pit latrines for sanitation while 239 have no electricity and 37 no sanitation at all. Yet, in 2013, Minimum Norms and Standards for education facilities was approved by the government, requiring that by November 2016 all infrastructure failings be addressed. Seven years later the government has catastrophically failed to alleviate distress at numerous schools in the country.

There are a host of interventions which would improve education standards in South Africa, such as desperately needed infrastructure upgrades, smaller teacher-to-learner ratios, more accountability and professionalism in the teaching profession and less unionisation, to name but a few.

However, this article is not about these matters, it is about the importance of early childhood development (ECD) and how focused ECD programmes can lead to better outcomes and help adults as well.

ECD refers to the period when children are between the ages of one and six, before they enter primary school. It is a period of immense importance in a person’s life and can holistically shape their intelligence, personality and social behaviour. It plays a huge role in shaping who you are from childhood through to adulthood.

Unicef understands this, highlighting that during these early years brain development is incredibly rapid and critical. A lack of quality stimulation or support during this time can significantly impair a child’s development.

Children who receive support in their earlier years are more likely to achieve strong educational outcomes at school, achieve higher economic status and income, live a healthier life and avoid criminal activity. Importantly, Unicef highlights the need to improve ECD as an investment and not a cost. Its estimates indicate that for every dollar spent on early interventions the returns can be four to five times what was initially invested.

There is extensive academic research to support these views: the most notable studies are the High/Scope Perry Preschool Project, the Abecedarian Project, and the Jamaica Project, all of which demonstrated how ECD interventions can play a critical role in shaping improvements into adult life.

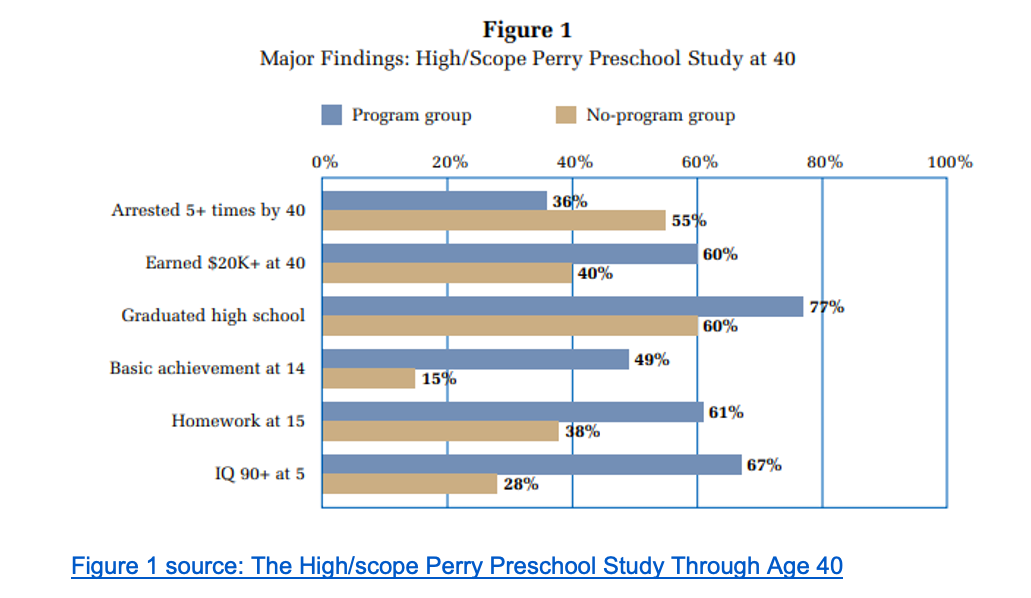

Take the High/Scope Perry Project, for example: researchers identified 123 low-income children who were assessed to be at high risk of school failure due to their socioeconomic background. They were all entered into a high quality ECD programme at ages three and four and then were tracked for a period of 40 years. The graph below summarises the key findings.

As can be seen, across multiple areas the programme group significantly outperformed those who did not receive high-quality ECD interventions. Educational and economic outcomes, in particular, highlight stark differences. These studies are increasingly forcing policymakers around the world to focus their attention on the importance behind building a strong ECD platform.

In South Africa these lessons and their importance are still to be learnt and implemented. There is no significant oversight or interrogation on the quality of ECD education in the government. Research on the sector in the country is limited. Research by Elsa Fourie from North West University highlighted grave concerns about the number of children who are receiving quality ECD education, with estimates that it is as low as 20%.

The state of ECD education in the country is largely informal and at times totally unregulated. For many parents, the core goal of an ECD centre or preschool is merely to keep their child occupied for much of the day. However, truly interrogating the education outcomes may well be an afterthought. So, when children in South Africa enter Grade 1 there are stark differences in their cognitive and comprehension abilities. This can only deepen inequalities in the educational system.

A lack of standardisation or oversight of expected outcomes from ECD is going to place tremendous strain on teachers, particularly those at a Grade 1 level who will be attempting to fill any education gaps in their students before they can progress. This is also clearly not working — as indicated by the country’s poor performance in literacy tests.

While there are a multitude of problems in South Africa’s educational system, there is no doubt that ECD is a core area where the right levels of support could have a lasting and sustained impact on improving educational outcomes. Yet it is totally understated in government policy and receives little to no attention from the state.

The government is unknowingly sabotaging higher education outcomes. ECD must receive the prominence and attention it deserves if the country is to advance. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

One has to wonder why the anc government is sabotaging education. Could it be that they – like the NP government of so many years ago – also don’t want too many “clever blacks” upsetting their trough….?