There are two really important questions regarding schooling as we sit through our lockdown bubble: When do we go back to school? (Q1). What do we do in the meantime? (Q2)

When do we go back to school?

This is the only question currently obsessing government, educators (including teachers, principals and departmental officials), parents and learners. It is obviously an important question, one that needs to be resolved as soon as possible. Parents and pupils are getting increasingly anxious about the school year slipping by. Uncertainty breeds fear, while knowledge is power, enabling people to act rationally.

To a considerable extent the answer to Q1 depends on health risks and when schools will be ready to minimise these. And the discussion is going to be protracted because as soon as the schools are reopened infections are bound to increase. All available data from around the world tells us that late-middle-aged and older adults and those with health complications carry the greatest risk.

Understandably, therefore, educators are resisting the Minister of Basic Education’s call, saying schools aren’t ready; the government is not doing enough, etc.

Watching Minister Angie Motshekga on 19 May declaring (not for the first time in the past five weeks) that schools would reopen for Grade 7 and 12 learners on 1 June, I was impressed. It seemed to me that, after weeks of dithering, the government had regained its mojo. She was assertive, well prepared and she and her deputy answered questions in detail and with confidence. I thought there was no way the minister would be so ballsy without having come to an agreement with the unions.

Alas! My optimism was dashed the next day, with Mugwena Maluleke of Sadtu declaring that schools would never be ready by June, and Basil Manual of Naptosa quoting evidence about the non-delivery of personal protection equipment (PPE) to schools.

Are these parties not talking to each other? What happened to the alliance between government and unions? Where is leadership? Confusion continues to reign.

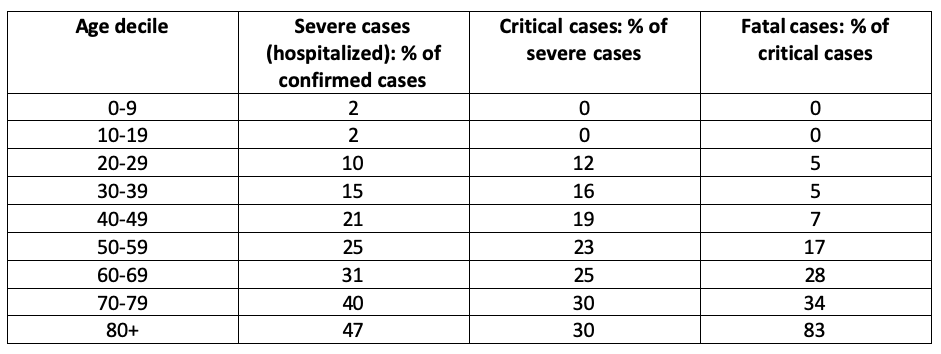

Government is missing a trick here. One way through a stand-off of this kind is to try the rational approach. For example, the probabilities of risks to learners and their educators are beginning to emerge, most notably through the briefing by the modelling team presented to the nation on Tuesday. The following table released during the briefing is arresting in the story it tells of the risk profiles of different age groups.

The very low risk to children under 20 is most striking: according to the modelling team no-one of that age group has died. This mirrors evidence from other countries. Furthermore, not only are children much less likely to be infected, but when they are infected they generally get the illness in a relatively mild form and hence are less likely to pass it on. As much as I love my granddaughter to distraction and am terrified of her catching the virus, these figures increase my confidence in sending her back to school.

Furthermore, for educators under the age of 50 – who don’t have TB, HIV, diabetes or any other co-morbid factor and who practice social distancing and good hand and face hygiene – the risk is also fairly low. The lesson is obvious: anyone over the age of 55 and anyone with a comorbidity should stay at home until further notice (which may be up to two years), but the rest should begin to emerge from lockdown. We need a rational debate, about the risks involved and the practices we need to optimise safety, not only at school but in transit to and fro.

A number of experts are arguing that we have passed the tipping point where the negative effects of the lockdown outweigh the potential negative effects of returning to school. There are three kinds of negative effects of lockdown: health, nutrition and education. On the health side, by staying at home poor children are not being screened for diseases which kill tens of thousands of South Africans annually and severely compromise many more, notably TB and HIV. They are also not getting vaccinated against other diseases like measles. Regarding nutrition, for many poor children the meal they get at school constitutes a high percentage of total food they receive daily, up to 100% in extreme cases.

In terms of the education they are missing, it is an established phenomenon that poorer children regress significantly in terms of reading and maths skills during the summer holidays.

Since the very first day of the lockdown, learners in Model C and independent schools have been using technology and print materials, given to learners to take home before the lockdown kicked in, to continue with learning.

On the other side of the educational fence, poor children, with no educational guidance, are falling further and further behind. These poor learners and their educators are slipping out of the habit of working, while parents are becoming increasingly anxious about the future of their children’s education.

During the first three weeks of lockdown, we undertook a small research study where we interviewed the main caregiver and up to two children in each of 16 families. This was not a representative sample, but the findings are nevertheless indicative of the kinds of educational inequalities in our society. Eight of the families lived in the suburbs, six in townships, one on a commercial farm and one in an informal settlement. Only seven families had regular access to the internet, including two of those living in townships, and a common complaint from those with internet was about the high cost of data. But all the families reported having cellphones.

Six families sent their children to independent schools (two of the low-cost variety), three to Model C schools, and seven to township public schools. Of the children attending township public schools, only one had received educational materials from their school prior to lockdown (which is contrary to the claim on the DBE website). Of the children at independent or Model C schools, only one was not receiving some kind of tuition daily: the rest were being kept busy through a combination of electronic and paper-based materials which they had taken home before lockdown. It is obvious that the lockdown is exacerbating the huge inequalities which, along with poverty, constitute the country’s greatest socio-economic problem.

What do we do in the meantime?

The national obsession with Q1 is distracting us from the even more important Q2, and failure to deal with it constructively is further deepening the inequalities in South African schooling. While government vacillates and conducts a war with the unions around Q1 through the public media, the large majority of educators and learners sit at home wasting valuable time. Ways need to be found to keep them busy, while minimising the health risks.

The first thing needed is clear and regular communication between schools and the families they serve. Regarding the modality of communication, national announcements, notices on the DBE website, radio broadcasts and newspapers can all help, but are not efficient in getting through to all families. For example, our survey of 16 families showed that only seven had heard, or heard about, the minister’s announcement made prior to lockdown. The most reliable channel to communicate with families is by cellphone. The first thing that schools should be doing is establishing class-based cellphone networks with all parents, supported by newspaper and radio announcements. Schools need to communicate regularly with all parents.

Here too, in schools serving middle-class families such networks were in existence before the lockdown and continue to provide communication channels during these troubled times. All schools need to follow suit and maintain these networks once lockdown is lifted: this is one of a number of ways in which practices established as a result of Covid-19 can continue to serve beneficial purposes after the pandemic has passed. And the first thing that school management teams (SMTs) should be doing is setting up communication networks with parents.

… The visits could be done in rotation, by grade so that schools are sparsely populated at any one time, and under conditions of social distancing and strict hygiene. This could happen once a month, or less frequently, when learners collect the programme for the month, for as long as the lockdown continues.

But it is not practical to distribute educational materials by cellphone. DBE currently has much study material on its website, but how are families to receive these activities, or even to know of their existence? The large majority of South African families do not have access to the internet and those that do, unless they are in the most affluent 5-10% of the population, complain about the cost of data. Downloading educational materials is a data-heavy process and so, while the DBE, provincial departments and many commercial sites are offering free access to materials, these are only accessible to a small minority.

TV offers great scope for teaching and learning and a large volume of curriculum-based material is available for broadcasting. Indeed DStv Channels 317 and 319 and OpenView Channel 122 are currently broadcasting such material.

Unfortunately, our small survey of 16 families revealed that, even among the middle classes, TV is a much under-utilised channel of communication on educational matters. Part of the problem is that learners and their parents are unaware of its existence and, if they do know about it, they are not clear how it can be utilised. Then there is the matter of the cost of a decoder, although this is relatively inexpensive (R1,600) for OpenView.

But far and away the most useful channel for providing learners with study materials is through print, the medium which is both most familiar to learners and parents and already available at no additional cost in the form of workbooks, textbooks and readers. Unfortunately, most learners do not have these materials at home. They need to get these materials, together with simple guidelines and a study timetable which lists the topics to be studied, how to do so, where supporting materials can be found in the books, and how the TV broadcasts can help.

The best way for families to receive the print materials is for learners to fetch them from school. The lowest risk strategy is for learners to travel to school, given that children exhibit the lowest risk of being infected and of infecting others. These visits also provide an opportunity to screen learners and to provide other health services. The visits could be done in rotation, by grade so that schools are sparsely populated at any one time, and under conditions of social distancing and strict hygiene. This could happen once a month, or less frequently, when learners collect the programme for the month, for as long as the lockdown continues.

Such a distribution strategy would be preceded by small teams of SMT members and senior educators meeting at school, to sanitise the places to be used during distribution and to prepare the materials and work programmes. Indeed, much of this work has already been done. Educators older than 55 and those with co-morbidities would be excused from such duties, but all educators should be mobilised to prepare the materials from home. The use of private cars and lift clubs to travel to and from school would further minimise risks.

While the national debate on when to return to school rages inconclusively, poor children are suffering in terms of their health, nutrition and education. Eight weeks into the lockdown, and counting, ways need to be found of addressing these issues as a matter of urgency. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider