Parents around the country are complaining at having to cope with doubling as teachers for children kept home during the lockdown. But home schooling or distance learning should be no problem if properly organised. And it could give better results than conventional classrooms.

The distance learning experience of New Zealand seems to have good lessons for the South Africa of today. A mix of historic practice and the state-of-the-art digital programmes now operating in that Pacific country might well help lift South Africa’s dismal education sector to a new and better level.

However, any such system would require not only good, highly qualified teachers, it would also need the support at a national level of both the government and the national broadcaster. This I can say from personal experience, having spent nearly two years on the road around New Zealand, living in a converted bus with my wife, Barbara, a dog, a cat and two young children. There were also two mice, but that is another story.

It was 1976 and daughter, Ceiren, was seven and her brother, Brendan, four when we set off from Auckland bound for the capital, Wellington, the base of New Zealand’s Correspondence School, to enrol the children. The school, now known simply as Te Kura (The School in the Maori language) was, and remains, the largest in the country, with an enrolment of some 27,000 students in 2019, ranging from pre-school to adults.

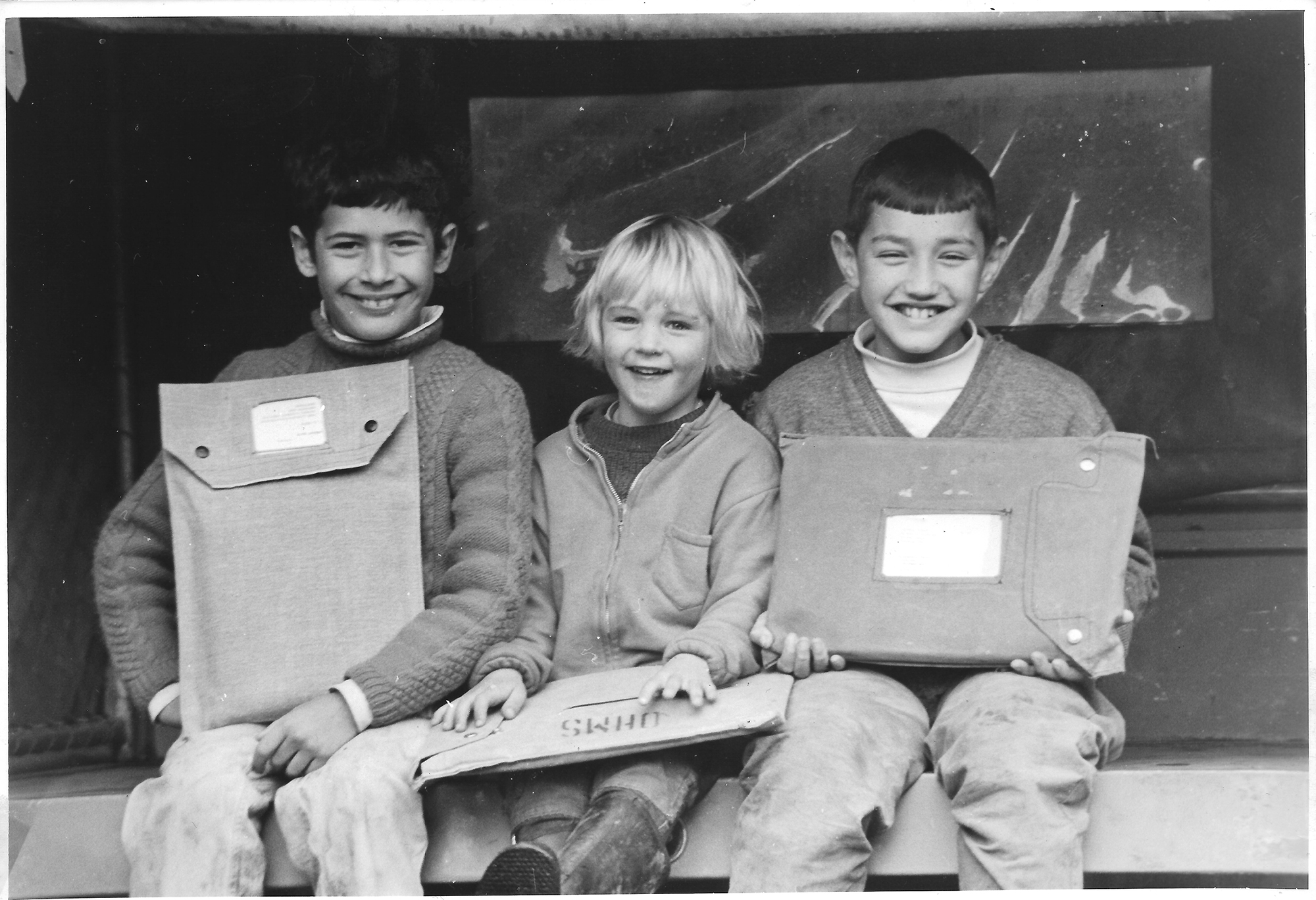

Brendan Bell, aged five, with two fellow Correspondence School students from a rural farmstead in New Zealand. (Photo: supplied)

Schooling in a bus. Barbara Bell with daughter, Ceiren and son, Brendan. (Photo: supplied)

But in those days before the internet, cellphones, tablets and personal computers, the postal service and radio were the means of communication as they had been from the time the school began in 1922. It was established, in those days before a comprehensive road network, to provide primary school education to a largely farming community scattered across the two major islands of a sparsely populated country.

However, while sealed roads — and schools — eventually reached almost every corner of the country, the Correspondence School continued to grow. So too did the range of education offered. By 1976, the school catered for more than 12,000 students ranging from preschoolers to prisoners and other adults taking a second chance at secondary schooling, along with provision for students with special needs and for New Zealanders living abroad.

For those children, across a wide age range, unable because of disability to attend standard schools or who required extra educational help, there was what was known as the Home Training (HT) section. Given the lack of facilities for such children in South Africa today, the HT model could provide some answers to help parents — usually mothers — dealing at home with children who sometimes have severe difficulties.

We discovered this range of educational opportunities —since then greatly expanded — when we arrived in Wellington in our bus. Because Barbara and I, in exile in Zealand, had been involved with, and taught in, an experimental primary school using non-standard methods of teaching, we opted to enrol our children in the then small individual programme section (IPS) of the Correspondence School. This section provided “normal” academic-level programmes, mainly for students unable to cope with standard class work.

As opposed to the usually age-based classes, IPS programmes were geared to the student’s specific interests, while encouraging the core competencies of literacy and numeracy. We had used this system in a collective classroom environment in the government-financed “alternative” school we had worked in.

The IPS, like most other sections of the Correspondence School, operated with a team of teachers who, every fortnight, posted out, and received back, packages of letters, books, printed material and the then fairly recently introduced cassette tapes. Families who could not afford a tape recorder were loaned one by the school which, in 1976, had close to 20,000 tapes in circulation.

Today, the digital revolution is everywhere in evidence with online kura (school) meetings and discussion forums. Even students in established schools wishing to study subjects not available where they are currently enrolled, can take up courses.

But, 44 years ago, students and teachers communicated with one another on tapes that were exchanged in school packages every two weeks. These packages came in the form of green canvas envelopes that were free of postage charges and were large enough and strong enough to ferry books, worksheets, tapes and other material back and forth.

Each established class and section of the school also had specific, one-hour slots on national radio where individual teachers addressed their students and played contributions such as poetry and songs recorded by their charges. Teachers interviewed agreed unanimously that they were better able to deal with the needs of their students through this distance method than in a regular classroom.

“With 30 or more children in a class, I can perhaps spend a couple of minutes at a time with any one student; through correspondence I can spend time — hours if necessary — on individual students, assessing their needs,” was a common refrain.

In some rural areas, groups of students, often studying at different levels, would come together each day to work collectively, helped by a parent or, in some cases, a qualified teacher living in their area. The ethos of the school then was — and is still — that it operates in partnership with te whanau (the families), students, schools and communities.

During holidays, groups of these distance-learning students and their families would sometimes come together of their own accord and the school also organised twice-yearly camps around the country that drew in families from a wide area. Being on the road, we were able to call in, from time to time, on rural schools and fellow distance learners, providing our children with needed social interaction with their peers that camps and visits were— and are still — set up to provide.

With much of South Africa’s education system in a shambles, the examples provided by New Zealand’s distance learning experience could provide some answers. But leaping hopefully into the digital age with tablets may not be any solution.

Although most of the Te Kura courses today are online, the school stresses that students should not “just sit in front of a screen”; that they should get out and “explore the world”. But it might be largely meaningless to do so without guidance and advice being available — and without the ability to think critically, an attribute that good education should encourage. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider