There are probably fewer than 100 big tuskers left in Africa. In its haste to sanction elephant hunts despite offers to save them, the Gaborone government is ignoring both the critical role elephants play in maintaining healthy ecological systems and the future of elephants on the continent. Instead, it’s selling its inheritance for short-term income from an extractive industry.

At a major hunting auction on 7 February, six of the seven packages (of 10 elephants each) were sold to the same white-owned hunting companies that benefited from Botswana’s hunting industry before the 2013 hunting moratorium. One package failed to reach the reserve price.

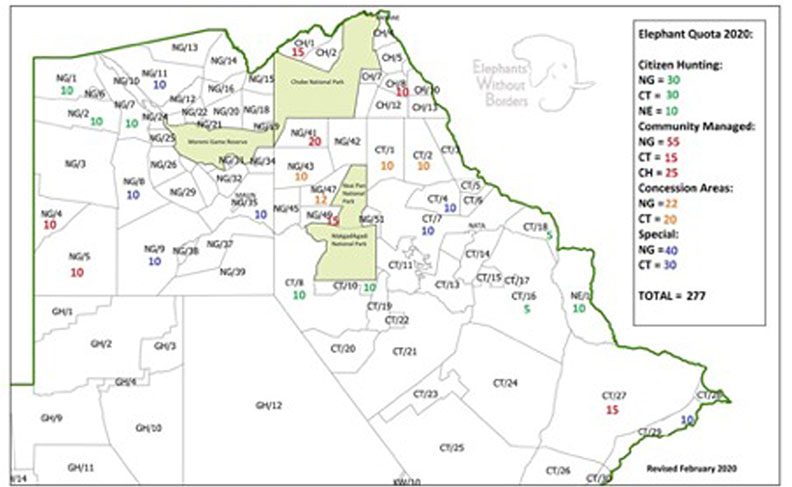

These 70 licences form the “special elephant quota” of the 2020 hunting quota of 272 elephants. Advertisements for the auctions were only released to the public on 3 February. Interested bidders then had only until 7 February to register – at best an indication of the rushed way in which the reintroduction of hunting to Botswana has been managed; at worst, an indication of pre-decided outcomes.

The EMS Foundation, a South-African based conservation advocacy and research organisation, attempted to bid for the licences. It wrote a letter to Dr Cyril Taolo, the director of Wildlife and National Parks, requesting a revision of the qualifying criteria “to enable us to bid on the hunting packages on the 7th of February 2020 with the express intention that the elephants included in these packages are not hunted should our bids be successful”.

The letter further noted that “we wish to purchase available licences with no intention to hunt elephants, but for the money to be appropriately distributed in a way that benefits conservation”. Local communities would therefore not be deprived of the revenue that would otherwise accrue through auctioning off elephant hunts. Of course, the hunting outfitters would lose out, but communities would have cash in hand, provided appropriate governance mechanisms were established through which to equitably distribute the revenue.

The letter objects to the fact that the bid criteria “explicitly excludes tourism operators or foundations/companies such as ours that do not want to hunt elephants but do desire to fund non-consumptive conservation in Botswana”. Beyond the EMS Foundation, other donors offered funding to buy 10 elephant hunting licences on auction to prevent the animals’ deaths. Clearly, those who are willing to invest directly in conservation activities, and even subsidise revenue shortfalls in areas where non-consumptive tourism is apparently unviable, are overtly excluded from the bidding process.

The licences on auction were 10 each for areas CT4, CT7, CT29, NG8, NG9, NG11 and NG35. Ngamiland concessions 8, 9 and 11 are held by local communities.

Local communities in NG3 objected to hunting in their concession (where a hunting disaster occurred in 2019 involving the shooting of a collared research bull). Consequently, there is no 2020 quota for NG3, but the quotas for some of the neighbouring concessions appear too high.

There has also been no consideration given to maintaining hunting-free corridors in critical areas such as NG41, which will be auctioned later. This suggests that the quota is not based on science; the way in which it has been divided up is arbitrary. Moreover, a confidential letter from a community in NG8 has expressed to the government that it does not want hunting, which it sees as undermining its projects to raise support for building self-sustaining tourism initiatives. If there is science to support the quota and the way in which it has been allocated, this should be made publicly available. Until such time as this is provided, it would appear responsible for the international community to ban trophy imports from Botswana.

The results of the auction are telling. Six 10-elephant packages sold for between $330,000 and $435,000 each. The package for CT29 did not sell because it did not fetch the minimum clearing price. The government amassed a total of $2,355,000 for six packages. There is no indication of how this money will be spent.

Successful bidders will now look to sell elephant hunts for upwards of $60,000 per elephant, normally paid into foreign bank accounts. At an average cost of $39,250, the margins are impressive. But who will benefit? Hunters would have us believe that local communities are the primary beneficiaries. However, one study showed that only 3% of hunting revenue eventually trickles down to them; at best hunting only contributes an average of 1.8% of African tourism revenue.

CT4 and NG9 both went to Jeff Rann Safaris, which is now offering a 10-day elephant hunt for $85,000 on its website. A joint shareholder is Professor Joseph Mbaiwa of the Okavango Research Institute who has long been an advocate of lifting the Khama-era moratorium on hunting in Botswana. Mbaiwa became a shareholder (in November 2019), shortly after President Mokgweetsi Masisi decided to bring hunting back to Botswana last year. CT7 went to Leon Kachelhoffer, NG8 went to Clive Eaton (along with NG11, in partnership with Kaz Kader). NG35 went to Grant Albers (apparently for Kerry Krottinger, a Texas oilman with a long history of big game hunting in Africa). There are no obvious local community beneficiaries apart from the potential allocation of meat and tracking jobs.

In response to the auction, former president Ian Khama, commented:

“I have been against hunting because it represents a mentality in those who support it to exploit nature for self-interest that has brought about the extinction of many species worldwide. This policy is driven by those who represent an industry that capitalises on ecological destruction. The negative effects are already being felt in the tourism industry, which will threaten our revenues and employment that hunting proponents pretend they want to improve. No scientific work was done on numbers to hunt or places to do so. This new policy will also demotivate those who are engaged in anti-poaching who are being told to save elephants from poachers while the new regime is poaching the same elephants but calling it hunting. How can this government now be trusted to manage controlled hunting despite the rules whilst failing to control poaching?”

Masisi has been lauded by Safari Club International (SCI)’s CEO W Laird Hamberlin, as a “role model for African wildlife conservationists” for reintroducing trophy hunting. He was awarded the “international legislator of the year” award in Reno, Nevada last week at the annual SCI Convention. Clearly, the SCI’s infamous lobbying efforts have paid off.

There is no guarantee that local community members will benefit from these licences distributed to wealthy hunting operators. Community-based natural resource management schemes were a governance mess long before the hunting moratorium was imposed.

There is no good ecological or economic reason to kill any of Botswana’s bull elephants. Hunting will simply create a contest for increased poaching. According to a scientific paper published in Current Biology, over the past two years, an estimated 378 elephants were poached in the country.

Hunting also traumatises elephants and makes them more aggressive towards humans, which will exacerbate human/elephant conflict (HEC). One of the key rationalisations Masisi used to reintroduce hunting was that it would reduce HEC. There is no evidence to support this claim. According to one recent academic paper, most current measures to reduce conflict (such as hunting) “appear to be driven by short-term, site-specific factors that often transfer the problems of human-elephant conflict from one place to another”. Hunting is not a solution; better land-use planning is.

Perhaps of greatest concern regarding Botswana’s 2020 elephant hunting quota is that NG41 – owned by the Mababe Community – has been allocated 20 elephants (the single largest allocation, to be auctioned soon). As is clear from the map, this concession links the Okavango Delta to Chobe National Park and is home to most of the last of Botswana’s great tuskers. Botswana’s Weekend Post reported that ‘a number of concerned businessmen in the tourism sector are chronicling how the former Minister [of Environment, Kitso Mokaila] is lobbying for South Africa’s Johan Calitz of Johan Calitz Safaris to lease a Mababe Concession (NG41).’

Concerning, too, is that in NG49 and CT8, 25 elephants will be hunted along a relatively small area on either side of the Boteti River. The Tuli Block area will see 55 bulls killed in one year. In 2013, four scientists published a paper showing the effects of hunting in that area:

“Hunting of bulls had a direct effect in reducing bull numbers but also an indirect effect due to disturbance that resulted in movement of elephants out of the areas in which hunting occurred. At current rates of hunting, under average ecological conditions, trophy bulls will disappear from the population in less than 10 years. We recommend a revision of the current quotas within each country for the Greater Mapungubwe elephant population, and the establishment of a single multi-jurisdictional (cross-border) management authority regulating the hunting of elephant and other cross-border species.”

The quota allocation is a stark indication that the DWNP has given in to the hunting lobby with no appreciation for the critical importance of older elephant bulls for maintaining elephant institutions and ecological functionality in an open system. It has also ignored the fact that any big-tusked bull is prized by photographers and can be photographed thousands of times during its natural lifetime.

Wisdom suggests that Botswana should abandon short-term rent-seeking in favour of long-term ecological sustainability as the foundation for its economy. Why not allow any willing bidder (such as the EMS Foundation) to pay for these licences if that raises revenue to conserve magnificent bull elephants instead of eliminating them? The fact that conservation organisations are locked out of the bidding shows the hold to which the hunting outfitters and groups like the SCI have on Botswana’s leadership. It’s not about income but in whose pocket it ends up. DM

Ross Harvey studied a B.Com in Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the University of Cape Town (UCT), where he also completed an M.Phil in Public Policy. At the end of 2018, he submitted his PhD in Economics, also at UCT. He started his wildlife research career at the South African Institute of International Affairs, where he worked as a senior researcher from 2013 to 2019. His initial work oversaw a project that examined every element of the ivory trade, from park to port to end consumer. He has published in one of the world’s top journals, Ecological Economics, and a wide array of other outlets. Ross is currently a freelance independent economist who works with The Conservation Action Trust.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider